By Vasabjit Banerjee and Prashant Hosur Suhas

In the aftermath of the February 14, 2019 Pulwama attack in Indian Kashmir, where 44 Indian paramilitary personnel were killed in a suicide attack conducted by Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), India struck a target in Pakistan on February 26. The strike on the JeM camp in the city of Balakot in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province by 12 Indian Mirage 2000 aircraft was the first aerial bombardment of Pakistani territory since the India-Pakistan War of 1971. On February 27, Pakistani aircraft, either F-16s or JF-17s, shot down an Indian Mig-21 aircraft. The Pakistani aircraft were intercepted during an attempt to cross the line-of-control between Indian- and Pakistani-administered Kashmir for a retaliatory bombing run. There are reports of a Pakistani F-16 being hit, too.

Now that India has taken a watershed decision to use air power to fight terrorism, it will increasingly find itself in the line of fire from the Pakistan Air Force (PAF), and must account for further escalation. Consequently, the debate on India’s air strategy has exited the theoretical realm and will have significant real-world implications.

Besides the air-battle revealing India’s continued need to upgrade its fleet of fighter and fighter-bombers, it also brings to fore the central issue facing the Indian Air Force (IAF): how is it placed to handle a potential war with Pakistan and a two-front war with Pakistan and China? Evaluating the capabilities and constraints of the PAF and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) indicates that the key factor determining the IAF’s relative preparedness for a war with Pakistan is modernization — but for a two-front war with China and Pakistan, the IAF also has to correctly anticipate China’s level of involvement.

India follows a “tip of the spear strategy” wherein a few squadrons of advanced aircraft, like the Russian Su30-MKI and the French Mirage 2000, are backed by large numbers of 1960s vintage Russian MiG-21s. The MiG-21 has been the mainstay of the IAF for decades: The IAF still has six squadrons of the MiG-21 Bison variant, which amounts to roughly 96 to 108 jets. However, due to frequent crashes and resultant fatalities, efforts to phase them out are ongoing. Most recently the Rafale deal with France sought to be a step in that direction. The indigenously manufactured Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) is also being inducted. However, the Rafale acquisition process has been beset by political acrimony centered on accusations of kickbacks. The LCA took three decades to develop, yet only 16 will be operated by the air force by March 2019. In contrast, the process of replacing the advanced aircraft is well underway. India now has 11 squadrons of the Russian Su-30MKI Flankers, which are among the most advanced fighter jets in the world. India also has three squadrons of Mirage 2000E/ED/I/IT; four squadrons of the Jaguar IB/IS; and three squadrons of the MiG-27ML/MiG-23UB Flogger.

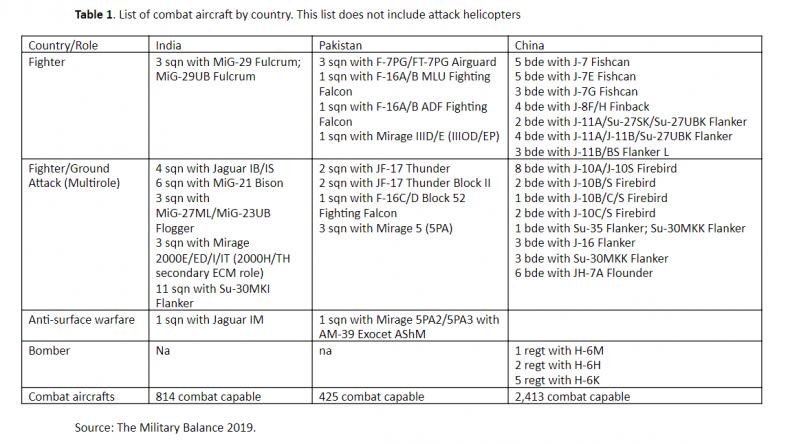

With regards to a war with Pakistan, the IAF is better equipped than the PAF. As Table 1 shows, the IAF has a bigger fleet, a sizable proportion of which are advanced fighter jets like the MiG-29 Fulcrum, Su-30MKI, and Mirage 2000. By comparison Pakistan’s most advanced fighter jets constitutes the American-made F-16 and to an extent the JF-17 Thunder that was co-produced by Pakistan and China. Pakistan’s current economic situation will prevent it from undertaking major modernization of its fleets or increasing its numbers of squadrons. Therefore, the IAF has a clear advantage over PAF in material terms. However, unlike China, neither the IAF nor the PAF have aircraft that are dedicated bombers. India largely relies on multirole aircraft and considers them as sufficient to achieve its strategic goals.

When the PLAAF is added to the equation, however, the IAF faces a more complex problem. China has been rapidly modernizing its military and has also expanded the size of its fleet. As shown in Table 1, China has 2,413 combat capable aircraft, almost twice the number of aircraft possessed by India and Pakistan combined. When we account for China’s capabilities in conjunction with Pakistan’s capabilities, the IAF is at a disadvantage.

However, this equation is not straightforward. India is not the only threat that the Chinese need to prepare for. In fact, India is not even a primary threat. China’s military modernization is geared toward the United States and Japan. Therefore, a significant proportion of its capabilities will always be dedicated toward the United States and Japan – and possibly also Russia. As a result, in any two-front war scenario involving India against Pakistan and China, China may deploy only a certain proportion of its capabilities. This must be kept in mind before we pass judgement on the IAF’s preparedness. In contrast, the PAF can be expected to use its entire capability against India. However, given the current state of asymmetry between India and Pakistan, it is a situation the IAF will be able to handle.

Thus, all else equal, the two factors that can tip the balance against India in a two-front war are: 1) the rate of the IAF’s modernization, which involves phasing out the MiG-21s and procuring new platforms; and 2) the proportion of resources the PLAAF brings to the South Asian theater in a time of war.

A maximalist strategy for India would be to outspend Pakistan and China and have a fleet that is the size of (if not bigger than) the PAF and PLAAF combined. However, given the demands on India’s exchequer this may not be possible. Therefore, in addition to modernization, the Indian security community must spend a significant amount of intellect to realistically assess the expected level of Chinese involvement.

In any strategy of a two-front war, India can factor in the international scenarios where closer ties with Japan and the United States will help India’s cause in deterring China from deploying a greater proportion of its air force against India. Given U.S. exigencies in Central and Eastern Asia that can curtail its commitment, India may encourage the idea of Japanese rearmament,which Japan is beginning to slowly undertake, and which is supported by U.S. President Donald Trump. Japanese rearmament will assuredly create greater challenges for China on its eastern front, which will invariably mean designating lesser resources toward its southwestern front against India.

Vasabjit Banerjee is an assistant professor of political science at Mississippi State University. His primary research interests are contentious politics and the local political-economies of state-formation in developing societies; specifically South Asia, Latin America, and Southern Africa.

Prashant Hosur Suhas is an instructor of Political Science at Eastern Connecticut State University whose research focuses on international relations and comparative politics, with a regional focus on South Asia.

No comments:

Post a Comment