By Paul Nantulya

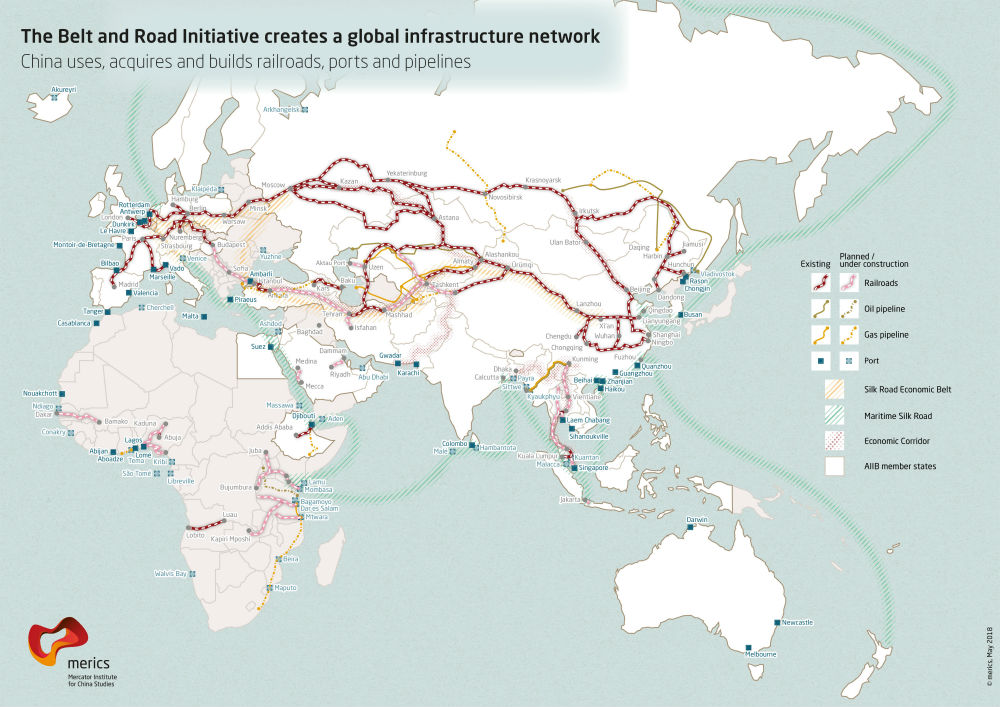

The debate on China-Africa relations has largely focused on Beijing’s massive infrastructure projects around the continent. Less noticeable but no less significant are its security activities, which have grown in scale and scope alongside the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), President Xi Jinping’s signature program to strengthen infrastructure, trade, and investment links in Africa, South Asia, and Europe.

The debate on China-Africa relations has largely focused on Beijing’s massive infrastructure projects around the continent. Less noticeable but no less significant are its security activities, which have grown in scale and scope alongside the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), President Xi Jinping’s signature program to strengthen infrastructure, trade, and investment links in Africa, South Asia, and Europe.

China’s growing military footprint in Africa is part of a policy that has at its core the rejuvenation of China as a “Great Power” or shijie qiang guo. In the past decade, it has pursued an increasingly competitive and assertive foreign policy that made a decisive break with Beijing’s decades-long approach of “hiding our capabilities,” “biding our time,” and “keeping a low profile”—a policy known as taoguang yanghui. According to Xi, “China now stands tall and firm in the East” and should “take center stage” in the world. This theme is echoed in the Diversified Employment of the Armed Forces, China’s defense guidance, which says that a world-class military deployable in a wide range of scenarios is indispensable in pursuing the “Great Rejuvenation of China.”

In 2015, China passed a law that allows overseas deployments of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and China’s other security forces, including the People’s Armed Police. Two years later, Beijing opened its first foreign naval base in Djibouti. In July 2018, the PLA constructed additional pier facilities at the base, and in November, it conducted live fire exercises there, employing armored fighting vehicles and heavy artillery—the first time China had conducted exercises on such a scale on foreign soil. That same month, PLA helicopters conducted a major training exercise to evacuate war casualties from a guided missile frigate off Djibouti’s coast, demonstrating China’s sophisticated ground and aerial capabilities in the region, in addition to its naval assets.

In 2018, the PLA conducted drills in Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, and Nigeria, while its medical units worked with counterparts in Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Zambia to develop their combat casualty care capabilities as part of decades-long relationships that involve arms sales and intelligence cooperation. In May, Burkina Faso established diplomatic relations with China and rescinded its recognition of Taiwan. The PLA is now developing ties to the Burkina Faso military that will likely feature training in counterterrorism and infrastructure protection, two key elements of Chinese engagement in the Sahel. In neighboring Mali, the PLA deployed its Sixth Battle Group, consisting of regular and Special Forces, to the United Nations-led Peacekeeping Operation in Mali (MINUSMA) to protect the mission’s Chinese and foreign staff and secure critical infrastructure. This deployment provided China with a security presence in a country that remains central in its ongoing effort to extend the BRI into the Sahel and the larger West African region.

Efforts to establish a comprehensive security assistance policy gained pace at the inaugural China-Africa Defense and Security Forum held June 26-July 10, 2018, ahead of the fourth Forum for China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in September. Defense officials from around 50 African countries developed new priorities for Chinese security engagement, including combating terrorism and piracy, and protecting Chinese nationals and economic infrastructure. These constitute an important part of the 2019-2021 China-Africa Action Plan, which established the overarching framework for China’s security programs in Africa.

Strategic Shifts and Emerging Policy

Africa fits into China’s grand strategy in three main ways. First, the continent represents an opportunity for Beijing to restore itself to its perceived rightful place of global preeminence at a time when Africa’s traditional partners such as the United States, United Kingdom, and European Union are perceived to be scaling back their African and global commitments. “With more than 5,000 years of civilized history, the Chinese nation created a brilliant Chinese civilization, made outstanding contributions to mankind, and became a great nation of the world,” said Xi during the 19th Communist Party of China Congress in October 2017. As part of this vision, Beijing is on a quest to expand its global economic and military influence and promote its models and norms. Its strengthened relationships with Africa, which are rooted in party-to-party ties and ideological bonds dating back to its support for anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements, are a major part of this quest because African support for Chinese positions at the UN and other bodies is beneficial in amplifying China’s voice on the global stage.

Africa represents an opportunity for Beijing to restore itself to its perceived rightful place of global preeminence.

Second, Africa is a strategic node in the maritime portion of the BRI known as the Maritime Silk Road that links China to East Africa, Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf, and Europe and was recently extended to West and Southern Africa. The World Bank estimates that investment links between China and the 65 countries that have signed on to the BRI account for 30 percent of global GDP and 75 percent of known energy reserves. China by 2020 aims to expand its GDP to $20 trillion and become a Great Power by 2049. The view from Beijing is that this target cannot be achieved without deepening its links with trade corridors along the BRI. China’s expanding maritime cooperation with Africa through port and infrastructure construction and counterpiracy patrols is part of this larger geopolitical and economic strategy.

Chinese companies are constructing rail links to connect landlocked Mali to ports in Dakar, Senegal, and Conakry, Guinea. Some of this infrastructure passes through areas affected by violent extremist groups in northern Mali, raising concerns about the safety of thousands of Chinese railway workers. This was a major driver of Beijing’s decision to participate in MINUSMA. Similar concerns informed China’s decision to train a local security force to protect the new $4 billion Mombasa-Nairobi high speed railway in Kenya, a showpiece of the BRI in East Africa and Kenya’s most expensive project to date. Because this type of training is normally assigned to elite forces of the People’s Armed Police, it will likely give the force its entrée to the African continent.

Third, the Chinese government has recognized the need to protect the growing number of Chinese expatriates working on its BRI-related projects dotted across Africa, numbering close to 300,000. African partners generally share Beijing’s security concerns given their vested interest in these projects. In Kenya, President Uhuru Kenyatta threatened to use executive powers to approve capital punishment for “economic saboteurs” after sections of the new railway had been vandalized. In Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni ordered the military to protect Chinese industrial parks and companies following a string of attacks on Chinese nationals and property. Similar attacks have occurred in Ghana, Lesotho, Madagascar, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zambia in recent years.

In line with the 2019-2021 China-Africa Action Plan, 50 new security programs have been established to address growing risks to the BRI through counterterrorism assistance, law enforcement, early warning systems, and infrastructure protection, in addition to traditional military assistance. These have in turn expanded the reach of China’s security services. The PLA’s Office of International Military Cooperation, an organ of the powerful Central Military Commission chaired by Xi, has been expanded in part to accommodate China’s growing programs in Africa. The PLA also upgraded its Peacekeeping Military Training Center in Huairou to support an ambitious program to train 2,000 international peacekeepers by 2020, many of whom will be African.

China’s defense guidance tasks the PLA with playing a more prominent role in Beijing’s new military diplomacy and national security strategy, a further shift away from “keeping a low profile.” The PLA Navy’s participation in international counterpiracy patrols in the Gulfs of Aden and Guinea, China’s first naval deployment outside Asia, is one example of the PLA’s recalibrated engagement. A naval presence in Africa will give China greater latitude to support its peacekeeping troops, humanitarian interests, and hard security operations. Together, these deployments form part of a repertoire of diversified deployments that the PLA refers to as “new historic missions.”

China’s maritime capabilities were critical in evacuating over 35,000 Chinese nationals from spiraling violence in Libya in 2011 and over 200 in Yemen in 2015. In April 2019, China’s second aircraft carrier—the first that was domestically built—is expected to come into service, with two more expected by 2025. The rapid growth is aimed at increasing the PLA Navy’s ability to operate in what it terms as the “far seas” that extend from the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean.

Unpacking China’s Security Engagements

China’s 2015 Africa Policy Paper calls for deepened military engagement, technological cooperation, and capacity building for Africa’s security sectors. While assistance to the AU and its regional security communities has increased significantly under this policy, Beijing channels most of its support bilaterally, with arms sales constituting an important element. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, China is now the top supplier of weapons to sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for 27 percent of the region’s imports between 2013 and 2017, a 55 percent increase over the 2008-2012 period. Algeria, Angola, Gabon, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Sudan, Sudan, and Uganda are among the 22 African countries that have imported weapons from China in recent years.

China has diversified its sales from small arms and light weapons to tanks, armored personnel carriers, maritime patrol craft, aircraft, missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles, and artillery. It is also increasingly focusing on building institutional capability in Africa’s security sector. In 2018, China’s State Administration for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND) announced it had concluded bilateral agreements with 45 African countries on the sharing of defense technologies and building defense industries.

The network of Chinese-built ports and infrastructure along Africa’s east, west, and southern coasts has positioned China to become a major player in Africa’s maritime space.

The network of Chinese-built ports and infrastructure along Africa’s east, west, and southern coasts has positioned China to become a major player in Africa’s maritime space. Djibouti’s Doraleh Multipurpose Port—built by the state-backed China Merchants Group to handle bulk cargo, containers, and oil shipments—is a few minutes’ drive from the PLA naval base. This unique arrangement allows China to mix commercial and military interests in Djibouti and the wider region. A new Chinese-funded electric railway for instance connects Djibouti to Ethiopia. Doraleh Port, in turn, connects Ethiopia and other Horn of Africa countries to Chinese-built port clusters in the Suez Canal, the Strait of Hormuz, and Gwadar, Pakistan, on the Arabian Sea. (Speculation is rife that China is planning to construct its second overseas naval base in Gwadar.)

Namibia’s Walvis Bay (formerly a naval outpost for apartheid South Africa) is another strategic hub along the Maritime Silk Road that has hosted numerous PLA Navy port visits and naval drills in recent years. The Namibian and Chinese navies share a special military relationship dating back to China’s support for Namibia’s independence war against South Africa. Some of Namibia’s most advanced naval assets are Chinese-supplied, including two maritime patrol craft delivered in October 2017. During a diplomatic function in February 2018, the Chinese Ambassador to Namibia described Walvis Bay as “the most brilliant pearl on the Atlantic coast of southwest Africa,” invoking China’s “String of Pearls” doctrine that refers to military and commercial nodes along China’s sea lines of communication from the Chinese coast to Somalia and Port Sudan.

The Namibian press has speculated that China seeks to establish naval facilities in Walvis Bay using the Djibouti model, pointing to similarities with the approach China used to acquire its Djibouti base, a process that started with the construction of a deep water port. The Walvis Bay Expansion Project is one of China’s most highly prized in Africa. Once complete, this port will connect southern Africa to China Harbor Engineering Company ports and infrastructure in São Tomé and Príncipe, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ghana, the Ivory Coast, and Guinea, and planned facilities in Gambia and Senegal. These maritime corridors—all critical nodes of the Maritime Silk Road—have important security dimensions.

The PLA Navy’s 27th and 28th Anti-Piracy Task Forces, for instance, visited ports in Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria after they joined the BRI. All three countries signed military agreements with China on training, weapons acquisition, information sharing, maritime navigation, and maritime security. The 28th Task Force also visited Gabon and South Africa. China’s 2017 Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative further underscores the security elements of the BRI. It commits Beijing to increasing counterpiracy training and joint patrols, conducting maritime security and law enforcement activities, and improving maritime domain awareness through cooperative use of China’s Beidou satellite system. The PLA Navy has been at pains to downplay the military significance of its activities on Africa’s seas. In 2017, China’s hospital ship, Peace Ark, visited seven coastal African countries where it conducted free medical and humanitarian services to thousands of African citizens in a major show of soft power.

Chinese peacekeepers in Darfur, Sudan. (Photo: UN/Stuart Price)

Peacekeeping is the other area in which China’s influence in Africa’s security sectors is growing. Beijing contributes more troops to UN missions than the other permanent members of the Security Council and is now the second largest financial contributor to UN missions. This is a strategic move to bolster Beijing’s image in Africa because not only do 78 percent of all UN peacekeepers serve in Africa, but nearly half of them are African. China’s peacekeeping strategy prioritizes support for the operationalization of the African Standby Force (ASF) and the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises. The China-Africa Peace and Security Fund committed $100 million to that end. In February 2018, this fund disbursed $25 million to the ASF’s logistics base in Cameroon. That same month, Tanzania opened a $30 million Chinese-funded military training center. In May, China signed an agreement with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to build its new headquarters in Abuja, Nigeria. In September, China began constructing a logistics depot in Botswana for the Southern African Development Community’s Standby Force.

The centrality of the Belt and Road Initiative to China’s global strategy suggests that China’s military and security footprint in Africa will continue to expand.

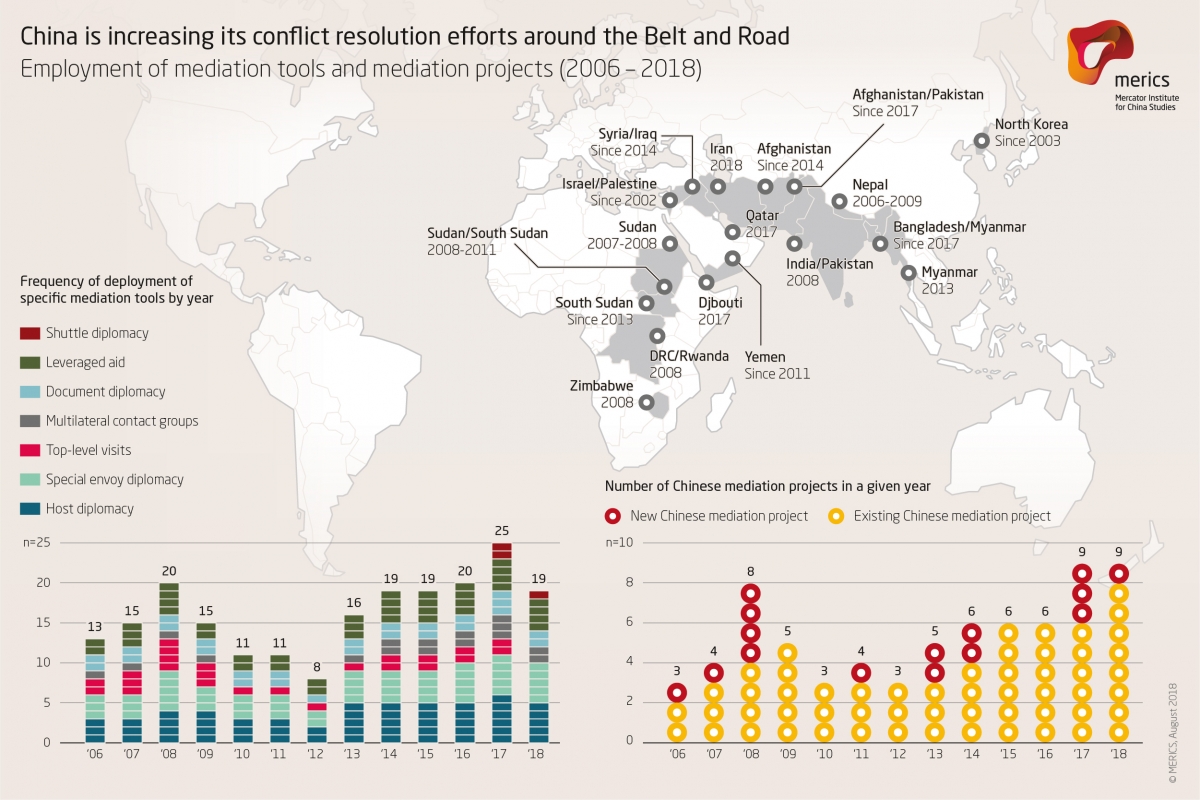

Given that BRI infrastructure is mostly located in highly insecure environments, the PLA has raised its own 8,000-strong Standby Force, even as it continues to support the ASF. This new force has been placed at the UN’s disposal for rapid deployment to conflict zones, the bulk of which are in Africa. According to the UN, 800 of its members will join the UN’s Vanguard Brigade, a new rapid-reaction force that can be deployed in 60 days. China’s peacekeeping and noncombat military deployments are concentrated in countries where its greatest economic and military interests are at stake. Instability in South Sudan, for instance, resulted in damage to Chinese oil infrastructure and attacks on Chinese oil workers. These missions are often supplemented by high-level Chinese mediation activities, a major departure from China’s longstanding principle of noninterference. China’s mediation initiatives in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe and its offer to mediate the Eritrea-Djibouti border conflict are cases in point. This mediation, notably, is often aimed at maintaining authoritarian leaders with whom Beijing has good relations and through which strategic investments in natural resources and infrastructure can be secured.

China also intends to double its training of African military professionals over the next three years. Several hundred officers study in China each year in schools such as the China Military Academy, the Dalian Naval Academy, the Air Force Aviation Academy, and the PLA’s National Defense University. Exposure to the Chinese approach to military management and control is central to this training. In the Chinese model, the PLA is subordinate to the absolute control of the ruling party, which itself supersedes the government and parliament.

In contrast, the majority of African constitutions place the military under civilian control and multi-party legislative oversight. Some African observers have therefore voiced concern that the wholesale application of the Chinese model could be harmful given the prevalence of personality-driven governing styles and the tendency to bypass constitutional checks.

(Image: Mercator Institute for China Studies)

What Lies Ahead

The centrality of the Belt and Road Initiative to China’s global strategy suggests that China’s military and security footprint in Africa will continue to expand. FOCAC has enabled China to fine-tune its policies in ways that advance Beijing’s economic and security goals. Ever mindful of messaging and image, China has gone to great lengths to reinforce that mutual respect, not hegemonic designs, lie at the core of its leadership ambitions. Furthermore, Chinese political and military leaders insist that China’s expanding military role in Africa and around the world is defensive and collaborative and that China offers viable alternatives as other world powers appear to be disengaging from the developing world.

China also makes clear that the BRI is compatible with the African Union’s Agenda 2063 by prioritizing open trade, industrialization, and infrastructure development—themes that resonate with African governments, and form part of the strategic partnership between the AU and China.

African citizens are increasingly pressuring their leaders to manage their security relationships with China in ways that avoid reinforcing these trends.

The more controversial aspects of China’s security strategy, however, will continue to shape the debate on China-Africa relations. The growing indebtedness of BRI partner countries to Chinese state-owned banks underwriting China’s megaprojects has raised alarms within both Africa and the international community. At the same time, anti-Chinese sentiment in many countries has grown, mostly stemming from hiring practices that favor Chinese nationals over locals. Additionally, there has been a proliferation of Chinese private security contractors operating in poorly regulated environments in Africa as BRI projects expand more quickly than oversight mechanisms can be adopted.

African citizens are increasingly pressuring their leaders to manage their security relationships with China in ways that avoid reinforcing these trends while promoting a broader concept of security beyond regime survival. This tension between African citizens and governments is likely to grow as China, in its drive to restore itself as a great power, seeks to expand its influence in Africa’s security arena.

No comments:

Post a Comment