By Lauren Jackson

In the course of her lifetime as a Tibetan Buddhist nun, Nawan Dima has watched brigades of foreigners, both violent and peaceful, traverse her home amid the clouds. The first came with force; as a young Tibetan girl raised in a Buddhist nunnery, Dima watched the Chinese People’s Liberation Army enter her village in the early 1950s, destroying her school in Khari Gompa.

In the course of her lifetime as a Tibetan Buddhist nun, Nawan Dima has watched brigades of foreigners, both violent and peaceful, traverse her home amid the clouds. The first came with force; as a young Tibetan girl raised in a Buddhist nunnery, Dima watched the Chinese People’s Liberation Army enter her village in the early 1950s, destroying her school in Khari Gompa.

Later, after fleeing over the Namgpa-La Pass to northern Nepal, Dima watched as a second wave of foreign men arrived, eager to summit the sacred homes of her gods — the now-legendary peaks of Jongmala (Everest), Lhotse, and Nuptse. Since then, the annual flow of tourists hiking by her monastery has grown to a small army, with tens of thousands of North Face-clad trekkers pouring money into the Nepali tourism market each year.

Over the last half-century, Dima has witnessed the remarkable transformation of Buddhism from an ancient but widely suppressed minority religion into a source of significant cultural and economic power in South Asia. Nepal is now the battleground for a broader geopolitical struggle between China and India, a soft power war in which Buddhism figures prominently — with the future of the religion hanging in the balance. Quietly and strategically, China has gained a clear advantage in this fight. By securing inroads in the Nepali tourism, trade, and transportation economies, Beijing is positioned to not only control the succession of the next Dalai Lama, but the lucrative Buddhist tourism market in south Asia as well.

A New Nepali Identity

The asphyxiating Himalayas have long served as a harsh natural buffer between India and China. Thanks to the terrain, Nepal — like neighboring Bhutan — remained isolated for centuries, with a Hindu monarchy governing autonomously with relative ease. During this time, Buddhists on the fringes of the kingdom maintained a quiet existence, unaffected even as myriad invasions pushed other Buddhist sects into small, remote enclaves of the subcontinent.

Nepal became politically salient in the mid-20th century just as the first foreign Everest expedition carved through the Himalayas. As a valuable gateway to western China and the only viable access route to the Tibetan plateau, Nepal was soon seen as a pawn in Britain’s “imperial chessboard,” according to Nepali journalist Sanjay Upadhya.

This “special relationship” between Nepal and India persisted even after Indian independence, with trade treaties ensuring the continuity of a semi-porous border. The Chinese invasion of Tibet further affirmed the value of diplomatic ties with Kathmandu; on March 17, 1950, India’s new Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru declared in parliament, “It is not possible for any Indian government to tolerate any invasion of Nepal from anywhere.”

In the decades since, India has maintained this position, controlling trade flows, flexing military dominance, and currying favor with Tibetan exiles. Their acceptance of refugees from the Tibetan invasion, willingness to house the Tibetan government-in-exile, and support for the 14th Dalai Lama, Lhamo Thondup, has stoked the Free Tibet movement and antagonized China. Yet China has decided to wait out the international condemnation, waiting for the Dalai Lama’s pending death so they can replace him with a Beijing-selected successor. In the meantime, and on India’s watch, they have staged a slow and nearly imperceptible economic invasion, challenging the long-standing balance of power in Nepal.

In the decades since, India has maintained this position, controlling trade flows, flexing military dominance, and currying favor with Tibetan exiles. Their acceptance of refugees from the Tibetan invasion, willingness to house the Tibetan government-in-exile, and support for the 14th Dalai Lama, Lhamo Thondup, has stoked the Free Tibet movement and antagonized China. Yet China has decided to wait out the international condemnation, waiting for the Dalai Lama’s pending death so they can replace him with a Beijing-selected successor. In the meantime, and on India’s watch, they have staged a slow and nearly imperceptible economic invasion, challenging the long-standing balance of power in Nepal.

“The Chinese are playing the long game,” Jayadeva Ranade, president of the Center for China Analysis and Strategy, said. “They are trying to move fast but not so fast that they alarm the Nepalese.” Still, the Nepalis suddenly find themselves surrounded on all sides by Chinese influence. From the western plains to the Himalayas, the Chinese have appropriated Buddhism to secure a clear economic and cultural advantage in the country, changing the praxis of the religion in the process.

“If they can get their teeth into Nepal’s economy they have control of Nepal for a long, long time,” Ranade said.

The Chinese are off to a strong start: Through foreign direct investment in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha, the extension of cross-border rations and pensions in the Himalayas, and a plan for an expansive railway project linking Chinese-controlled Tibet with Kathmandu, Beijing is well on its way to securing a long-standing goal. In Tiananmen Square in the 1950s, Mao Zedong said that Tibet was like China’s palm — its five fingers stretching across the Indian subcontinent had been stolen and must be liberated, he said.

“Nepal has always been one of the fingers that must be recovered,” Ranade said. “[Nepalis] should be concerned about that, though it may be too late.”

Claiming Lumbini: The Chinese Play on Buddhist Heritage and Tourism in Western Nepal

The birthplace of Lord Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, was a site of political irrelevance for thousands of years. Lumbini, a small town in the flatlands of western Nepal near the Indian border, was inaccessible to a majority of the world’s Buddhists, with most living in modern day Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

In recent years, however, Lumbini has become a lucrative attraction in the $70 billion wellness tourism industry in South Asia, where Buddhism has been used to market spa packages and meditation retreats to ashram-seeking, yoga-loving tourists around the world. This market is expected to grow in India, China, and Southeast Asian countries at the fastest rate globally.

“Everyone is instrumentalizing Buddhism — Nepal, Burma, Sri Lanka, Thailand but, most prominently, India and China,” Oxford professor of Nepali history David Gellner said. Competition to control major Buddhist heritage sites is fiercest in Nepal, where the political consequences — specifically in regards to Tibet and the succession of the Dalai Lama — are most significant.

India and China have taken different tacks in this fight, with the former playing the role of antagonistic older brother while the latter has come bearing gifts.

Indians often claim that the Buddha was born within their former borders in an attempt to capture a lucrative tourism market. In recent years, India’s Ministry of Tourism has officially promoted a cross-border Buddhist tourist circuit that includes Lumbini, an easy, cocky move which taunts Nepalis by underscoring how outflanked they are on the border. This has resulted in protests within Nepal, because, according to Gellner, claiming long-standing heritage of the site is a key way “to demarcate Nepal from the India. These public protests are really just agitations for Nepali nationalism.”

Prakash Rai, 25, is a Hindu man living in the foothills of the Himalayas, far from Lumbini. Still, when discussing religion, he cited Gautama’s birthplace as a source of national pride. “Hindus and Buddhists live together peacefully because Buddhism has been here forever,” he said. “The Buddha was born here, so we are all the same. The Buddha is one of us; we are happy to have Lumbini in our country.”

Yet while India and Nepal have squabbled for rhetorical claims to the site, China managed to buy control of Lumbini. In 2011, Beijing invested $3 billion, roughly 10 percent of Nepal’s total GDP, into a development project, bringing an airport, hotels, and a Buddhist university to the site. Through this investment, China gained access to Nepali trade flows in western Nepal, an asset for their Belt and Road Initiative, which will strategically diversify the Nepali economy. Since the announcement, Nepal has become even more open to Chinese support — particularly after India closed its Nepali border in 2015, resulting in a fuel crunch.

“This blockade hurt Kathmandu specifically, and [Nepali Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Oli] doesn’t want to repeat that,” Ranade said.

Writing for The Diplomat, Nepali economist Ashutosh Dixit said, “Although in describing the project China is putting a clear emphasis on inclusivity and ‘win-win’ cooperation, India harbors deep concerns about the implications of the projects for its strategic interests” regarding trade flows through Nepal. In the long term, Dixit believes China’s strategic investment will weaken New Delhi’s grip on Nepal, aligning Kathmandu with Beijing amid political volatility by side-stepping religious differences and affirming a shared Buddhist heritage.

However, more strategically, China has also secured a key property in the Monopoly game for control of Buddhism in the region. Now, Chinese officials determine who has access to worship at the site; meaning they can exclude the Dalai Lama, whom Beijing has described as a “wolf in monk’s clothes,” and prominent Tibetan separatists from accessing Lumbini. This is a significant win in China’s strategic goal of silencing critics who hope to maintain the salience of the movement to liberate Tibet. It also enables them to lay further claim to the succession of the next Dalai Lama.

While attempts to appropriate Lumbini and cement control of Nepal’s trade routes have been playing out between India and China, Nepal’s Buddhist population has had no platform to voice their concerns regarding an expansion of Chinese control in the country. Buddhist representation in the new Nepali parliament is “tokenized at best,” according to Gellner, and the ruling party is happy to claim Buddhist heritage in the interest of coalition building.

Pradima Ranapal, 21, identifies as a Newar Hindu and is from Kathmandu. Regarding religious hybridity, she said, “In our heart it is our feeling that every god is the same. [To Hindus,] Buddha is another god, it’s all shared.”

However, some Buddhists — particularly ethnic Sherpas and Tibetans living near the Himalayas — refute this notion. “Buddhism and Hinduism are very different. We have different gods and different festivals,” Pasang Sherpa, a 32-year-old trekking guide from Lukla, said. “Sometimes people say we are the same but we are not.”

Prayer flags at Gokyo Ri, Nepal overlooking the peaks of Jongmala (Everest), Lhotse, and Nuptse in the Khumbu Valley. Photo by Lauren Jackson.

Consolidating Economic and Religious Influence From Lhasa to Kathmandu

Dima, isolated at 15,000 feet for decades, now has a small Nokia phone, on which she likes to play Snake. After leaving her monastery, I passed one young monk, no older than 20, who had tucked a blocky first-generation iPod into the fold of his saffron robe. He was smiling slightly and bobbing his head to what was playing inside his foam-lined airplane headphones, left in the valley by a tourist from a Delta flight. When I asked what he was listening to, he clicked on the small white home button and “Starboy” by The Weeknd flashed up at us in monochrome.

With investment in Lumbini, China has used Buddhist diplomacy to consolidate a clear advantage in western Nepal. Their strategy for expanding their advantage to the rest of the country, however, requires gaining favor with Nepal’s small but powerful Sherpa Buddhist population in the Himalayas. To do this, they are stepping into a vacuum created by the tumult of globalizing forces, which have opened the Khumbu Valley to the world.

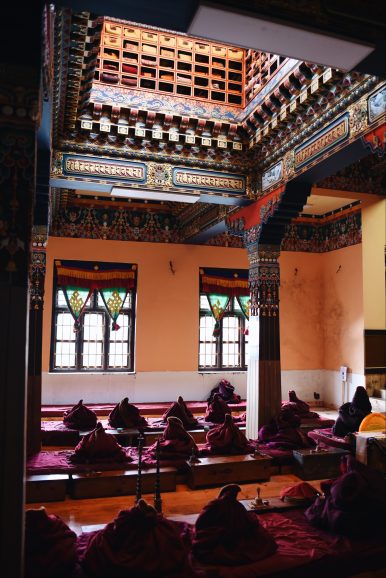

The Nepali Himalayas receive 35,000 tourists annually; few are aware of their role in the soft power-fueled, geopolitical struggle over the future of Buddhism. Instead, they arrive prepared to take and share photos of the craggy, yak-filled region, dotted with precariously perched monasteries and stupas.

The region has become Nepal’s main cultural export, flattened to the square frames of thousands of tourist’s Instagram accounts. The fame of the region has provided a measure of soft power to Nepal’s government, giving it a singular comparative advantage as India and China wrestle for control of other Buddhist heritage sites and of Nepali trade routes. According to the 2017 Economic Impact Research report, tourism, predominately to the Himalayas, is the largest industry in Nepal and “accounts for 7.5 percent of Nepal’s GDP and is forecast to rise 4.3 percent annually.” Now, the West has readily collapsed the Nepali national identity with its Buddhist cultural exports — buying into Hollywood depictions of Everest expeditions and prayer flag cameos at New York Fashion Week.

Tourists’ demands for wifi-access, Oreos, and Strepsils throat lozenges above the cloud line have stretched the slight but entrepreneurial Sherpa population. Recognizing the opportunity to provide assistance, China has exploited this need, unilaterally offering many in the region access to Chinese identity cards, which enable them to cross the border freely, buying goods in western China to bring back to Nepali villages, according to Ranade. They have also offered pensions and rations to those who, having strained as high-altitude porters in their youth, need support to sustain their prematurely weary bodies.

A shop in the Himalayas sells foreign imports alongside souvenirs depicting Buddhist symbolism mingled with Western wares. Photo by Lauren Jackson.

This strategy taps into the frustration of some Sherpas feel toward Kathmandu. Some locals charge that Nepal’s government is entirely absent from the region, non-reciprocally using them to maintain political power without accruing any of the benefits.

Pasang, the guide from Lukla, said, “We think the [Nepali] government takes quite a lot from us, but we don’t get anything back.” He referenced schools, healthcare, and agriculture as industries that receive minimal government support.

In response, many Sherpas are now sending their children to secular schools in Kathmandu or even in Tibet. “Ten or 11 years ago, everyone wanted their kids to be monks,” Rai said. “Now they think education is more important. In the monastery they just teach about Buddhism, but they want them to learn other things.”

This comes at a cost, however, to the continuity of linguistic, religious, and cultural tradition. According to Ranade, this is advantageous to China, who has sought to mitigate religious praxis in Tibet. In early March, “the mayor of Lhasa said they had successfully reduced the number of religious practitioners in Tibet to under 10 percent. No students or pensioners are allowed to worship and receive government support,” Ranade said. Reducing religious activity in Nepal’s neighboring Himalayan valley is a goal of Beijing, which “sees Nepal as a jumping off point for agitations in Tibet.”

This is working, Ranade claimed. He said he has been hearing rumors of an “uptick in criticism of the Dalai Lama and of Tibetan separatists” by Buddhists in the Nepali Himalayas.

Amidst a shifting balance of power, one final investment threatens to close the deal and consolidate Chinese control: a recently announced railroad linking Tibet with the Nepali Himalayas and Kathmandu.

The 660-kilometer extension of the existing Tibetan railway will cost roughly $2.5 billion, according to Nepal’s foreign minister, with that figure likely to increase due to the cost of building through the Himalayas.

View of the border between China and Nepal. Photo by Lauren Jackson.

In an interview with Nikkei, Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali claimed this would benefit Nepal’s economy. “Nepal is a landlocked country. To be developed, we need more and more connectivity,” Gyawali said. “We can import goods at lower cost. The main purpose of the train project is to link to the second-largest economy of the globe.”

However, Ranade sees a clear danger in the inevitable surge of Nepali debt to China. If the project is successful, Nepal’s “dependence on China will be complete,” he said. “While at the moment you have a bilateral relationship, the maintenance of the rail tracks and engines will all be done by the Chinese in the future,” meaning an ongoing presence in the country from Tibet to Kathmandu for years to come.

Still, when asked about both Lumbini and the railway, Dima — the Tibetan Buddhist nun-in-exile — looked up wearily and said, “We are Tibetan Buddhists with a long history. That history cannot be taken away from us.”

Sipping ginger tea in the Himalayan town of Namche Bazaar, Rai reflected on the future of religious praxis in the region. Despite the turbulent shifts of the last decades, he remained optimistic. “Even new generations will believe in a god always,” he said. “It is part of the land.”

The question that remains, however, is whose god Nepali Buddhists will worship — and at what cost.

A prayer wheel outside of Lukla, Nepal with a large mani stone inscribed with mantras behind it, a prayer for good luck. According to Rai, many Buddhist youth no longer know how to paint mani stones and villages rely on elders to continue the practice. Photo by Lauren Jackson.

Lauren Jackson is a graduate student studying diplomacy and public policy at Oxford. She is also a freelance journalist writing about religion and technology.

No comments:

Post a Comment