By Leo Lin

Both sides are sending positive signals, but the thaw seems increasingly like the calm before the storm.

Both sides are sending positive signals, but the thaw seems increasingly like the calm before the storm.

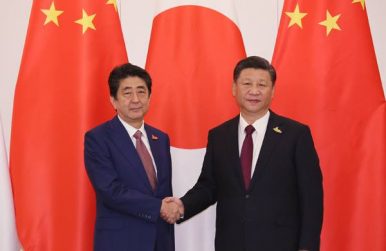

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to China on October 26 broke new ground for Sino-Japanese relations. While the visit could be noted as a success in terms of resetting the previously frozen relationship, under the surface diplomatic relations between China and Japan remain largely unchanged.

Abe’s visit to China raised new speculation on where Sino-Japanese relations will be headed in 2019. Despite the obvious warming of Sino-Japanese relations, Abe still hasn’t returned the relationship to its pre-2012 state. Nor returning the relationship to the pre-2012 high likely, given Japan’s recent announcement that it would improve its maritime defense capabilities by transforming its Izumo class into aircraft carriers, and Japan’s decision shutting out Chinese-made devices from government procurement. Sino-Japanese relations are poised for turbulence in 2019.

Historical issues have instigated tension between Beijing and Tokyo over the past decade. 2019 is a symbolic year for the Chinese Communist Party, marking the 70 year anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. Nationalistic fervor will certainly run high in China, and reminders of the Second Sino-Japanese War will most likely be used to justify the governing legitimacy of the CCP.

Chinese President Xi Jinping showed his restraint in December by sending verbal condolences instead of visiting the Nanjing Massacre memorial in person. And unlike previous years, this year’s ceremonies did not attract as much Chinese domestic media attention. While partially this was due to the U.S.-China trade frictions taking over the headlines and the attention of Xi, the lack of headline coverage for the Nanjing Massacre memorial sends a signal that Beijing is willing to tone down its anti-Japanese rhetoric. The longevity of this decision, however, will be tested in 2019.

Trade Prospects

One of the biggest takeaways for Abe in his trip to Beijing was the re-kindling trade relationship between the world’s second and third largest economies. China lifted its embargo on agriculture products from Japan in November, after a seven-year gap during which Japanese agricultural exports were limited due to the effects of the March 11 disaster and the subsequent nuclear accident in Fukushima. The rise in agriculture exports gave Abe a boost in his regional revitalization plans, and gave Beijing a fallback source safe from U.S.-China trade frictions.

Yet this improving trade relationship in the agricultural sector was overshadowed by the sanctioning of Chinese 5G and electronic products on the Japanese market. This impacts how Beijing perceives Tokyo’s willingness to move away from the United States and into Beijing’s sphere of trade influence. Tokyo, on the other hand, is also facing pressures from the United States, which has already hit Japan with steel and aluminum tariffs and is revisiting possible tariffs on automobiles. China is a backup for Japan in case trade negotiations with the United States go south, and Tokyo’s tilt toward Beijing can be seen as a negotiation tool to check Washington’s demands. In 2019, the trade relations between Japan and China will likely grow, but at a slow pace. Such growth might come in sectors such as agriculture and healthcare, where both countries can see comparative advantages.

Japan’s New Security Posture

The primary driver of Sino-Japanese relations in 2019 will be Beijing’s reaction to Tokyo’s new mid-term defense plans. Apart from the headline-grabbing decision to convert the Maritime Self-Defense Forces’ two Izumo-class helicopter carriers into aircraft carriers, Japan’s latest National Defense Program Guidelines (NDPG) also include budget provisions to upgrade Japan’s electronic warfare capabilities, purchase land-based missile defense systems, and research hypersonic weapons. While there are many historic “firsts” in the new NDPG, the most important point to make is the changing of Japanese security posture from reactive to proactive. The new NDPG still takes China as a hypothetical adversary, and if implemented the new plan will help Japan respond more quickly to territorial disputes, as well as placing an emphasis on the survivability of its assets.

For China, this change in the NDPG was anticipated, but its reactions to the change in Japan’s proactive postures were toned down. On Christmas day, Xinhua news agency, the state mouthpiece, cited the Chinese Foreign Ministry in a note “welcoming JMSDF maritime observers to China’s 70th anniversary [celebration] of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army Navy.” The news, which first broke from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, suggests that there is working progress between the JMSDF and the PLAN. While the exact context of the invitation, and whether or not Tokyo will accept the invite, is still speculative, it suggests that Beijing sees the dampening U.S. presence in the region as an opportunity to engage adversaries. Beijing will likely play down its reaction to the new NDPG in 2019, unless and until it finds the topic to be useful at another convenient time.

The Surprise Factor

While historic grievances, trade, and security issues remain as key areas to watch for in Sino-Japanese relations in 2019, North Korea stands out as the surprise factor. In 2018 the situation on the Korean Peninsula dialed down after the Singapore summit between the U.S. and North Korean leaders. However, the North has not pledged to denuclearize. The current peace process between South and North Korea suggests a détente, but the process is limited to those two countries.

The situation stands out for Japan especially as Japan is increasingly isolated in North Korean diplomacy. Among the Six Party Talks member states, Japan and Russia are the only countries with which Kim Jong un has not yet had a summit meeting. And as seen in the North Korean missile flyovers in 2017 and 2018, the risk of Japan being left out in any agreements on the Korean Peninsula cannot be overlooked. In 2019, China is the underdog option but a viable option nonetheless to bridge relations between Japan and the North, if Tokyo were to seek a summit meeting with Kim.

Conclusion

Overall, there will not be a complete reset of Sino-Japanese relations in 2019. Even as Abe’s visit to Beijing in October created synergy for better cooperation between China and Japan, the potential for the Communist Party to use historical grievances to find governing legitimacy, the growing technology sector race, and Beijing’s toned-down response to the new Japanese NDPG give the strong impression of calm before the storm. There are noteworthy agendas to promote bilateral relations in 2019, such as the invitation of the JMSDF to the PLAN exercises, and Japan’s engagement in the Belt and Road Initiative. But both Japan and China understand that their current engagement is opportunistic and short-term in nature. Above all else, China sees the opportunity to engage with Japan in order to mitigate the U.S.-China trade frictions. And for Japan, adopting warmer relations with China provides hedging against the Trump card.

No comments:

Post a Comment