BY WILLIAM HAN

In the summer of 2015, I left the United States. After growing up in Taiwan and New Zealand, I went to America to study before working in New York City. But in the end, I was unable to secure my permanent residency through a Green Card.

In the summer of 2015, I left the United States. After growing up in Taiwan and New Zealand, I went to America to study before working in New York City. But in the end, I was unable to secure my permanent residency through a Green Card.

As the prospect of my exile drew nearer, I correspondingly grew fascinated with a story I heard even as a child: in AD97, during the Eastern Han dynasty, China sent an explorer and envoy westward along the Silk Road to locate and to make contact with the Roman Empire.

His name was Gan Ying. He had been a veteran of China’s wars against the Huns under the famous General Ban Chao. And he almost – not quite – succeeded in meeting the Romans.

He was an Asian man who almost reached the heart of the ancient Western world, Rome. I am an Asian man who almost got to stay in the heart of the modern Western world, New York City.

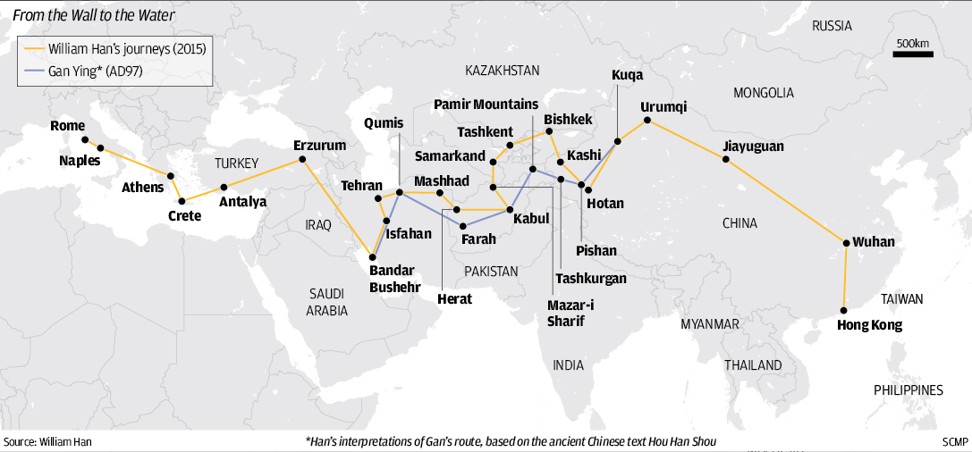

I conceived of the idea to travel along Gan Ying’s path, as recorded in that ancient text of Chinese history, the Hou Han Shu. I studied where he might have gone.

I began in Hong Kong. The journey then took me through parts of China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, and finally to Greece and Italy.

The journey took place over the second half of 2015, when the world felt like a very different place.

The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book I wrote about that journey.

From the Wall to the Water – Kabul

Past six armed guards, I entered a steel corridor that led up to the entrance of my Kabul hotel.

The corridor was divided into thirds, and the doors between the three compartments only opened when the guard on one side knocked, and the guard on the other side verified through a peep hole that it was his counterpart doing the knocking.

In the first compartment, I told the pair of guards that I had a reservation. They let me into the second compartment, which was built as a Faraday cage – no cell signal. Another pair of guards waited for me here, next to a metal detector. I said I had a reservation.

“What company?” asked one of the guards, a man of so much weariness in his face that I felt exhausted just looking at him. I said I was not with any company. This confused him. No one came here independently.

I added that I had emailed the reservation desk and received a confirmation. “What is your name?” I told him. “Show me your passport.” I did. He picked up the phone on the wall and presumably dialled reservation. “You’re not on the list. You can’t come in.”

I promised him that I had the reservation on my phone, and he said I had to retreat to the previous compartment and take all my luggage with me to get a signal.

I proved to him that I had a reservation. Next he went through all my luggage. Finally they showed me into the third compartment and into the hotel lobby, hidden behind the fortress.

I came to develop a theory of the Afghan hotel.

Hotels aren’t usually very interesting. Their function and their workings are basically always the same and always mundane. But I would make an exception for my Kabul hotel. This place was unlike any other where I had stayed.

Other hotels’ primary function was to ensure the guests’ comfort and to make them feel welcome and able to do what they had to do or wished to do. This hotel’s primary function was to assure its guests that they would not die here. It was armour. Everything inside was to be defended by this armour, and everything outside was a threat that the armour was meant to protect against.

But as much as actually serving as armour, the hotel’s purpose was also to endow its guests with the feeling of wearing this armour. This was the chief product that this hotel, and presumably other Kabul hotels, sold.

Attributes that, at any “normal” place of accommodation, would be considered bugs were here features. Most obviously, the inconvenience of heavy security checks and pat downs and going through four sets of steel doors each time one went outside was a necessity.

But it was not a necessary evil, not any more: with the inconvenience came the comforting feeling of being armoured, being protected, which was what the hotel was selling. An insufficiently inconvenient hotel would also seem insufficiently secure.

It was not unlike building an impractical and impedimental wall around one’s country: whether the wall actually did anything was secondary to the builders being able to point to it and say, “Look! We built a wall! We’re keeping you safe!”

Plastered all over the interior of the building were notices barring photography. There was a practical justification in preventing the photographing of security measures, but these notices were so ubiquitous as to demand that nowhere inside the hotel was ever photographed. Not the garden courtyard, not the divans in the lobby, not the balcony outside the restaurant on the top floor – even though an entire photo gallery appeared on the hotel’s own website, displaying all the “No Photography!” areas for all to see.

The purpose of preventing guests from taking photographs was therefore specifically to inconvenience the guests in a specific way that palliated their fear of their own mortality. It’s a security measure, you see!

After a while, even the bad food – the immutable breakfast of greasy sausages and very English baked beans with plasticky hard-boiled eggs and instant coffee made with lukewarm water with chunks of powdered milk floating in it like sewage scum – felt like a feature and not a bug.

The prison quality of the food served as a reminder that none of us was ready to die, definitely not here, that there were finer things to live for: a properly cooked steak, a real bottle of Bordeaux, a breezy summer evening on Lake Como.

If you give up the ghost in this town, the food seemed to be saying to the guest reluctantly swallowing this garbage, then I will be the last meal you ever put in your mouth before you die. And do you really want that? Like, seriously?

Gan Ying took much greater risks to get here, I told myself.

Sure, there was no IS back then and no truck bombs. But there were also no reliable maps, no planes, no phones, no internet, no trains or cars, and no idea where he was going. Modern terrorists could pose no more danger than ancient highway banditry.

I put on my Afghan outfit with the scarf half-covering my face and came back down to the lobby.

The woman at reception seemed impressed. “You look Afghan,” she said. But then she added, “You look Hazara. You know Hazara?”

The Hazara were an ethnic minority group in Afghanistan descended from the Mongols who trailed in the wake of Genghis Khan.

I said I did. “You know Daesh?” she asked. Daesh, the Arabic acronym for IS. “They like to kill the Hazara,” she said.

Damn it. But of course: the Hazara were Shiites.

Local yellow cab drivers couldn’t be trusted with not kidnapping me. So she called the taxi company with which the hotel had a relationship.

Twenty minutes later the driver came, a Hazara. We bore no resemblance to each other. But he also told me that I looked all right in my new get-up. “But next time,” he said, “leave the backpack.”

I told him to take me to Babur’s Garden, built by that founder of the Mughal Dynasty in India. Here was my first, modestly frightened, chance to see modern Kabul.

It was a city on edge, reeling from a series of bombings that killed dozens just days earlier. It was a city divided, between the foreign and the Afghan, between the rich and everyone else. It was a city half-crazed with fear and the injustice of chance, of fate, of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I imagined that Saigon circa 1973 might have felt a bit like this.

My driver was disparaging the Americans. “They said they were going to fix Afghanistan. Now they’re leaving, and Afghanistan is not fixed.” The Obama administration had announced its plans for withdrawal by the end of the year, 2015.

“In fairness to the Americans,” I said, “they have been here for fourteen years.”

I got all Chinese on him. “Only the Chinese could save China,” I said referring to – and giving a very compressed and not at all consensus view of – the civil war of 1945-49, after which US politicians would accuse each other of “losing China”. “So I say only the Afghans can save Afghanistan.”

“Yes, everything is good in China now. You have power, you have good lives …”

“I don’t know about everything …”

“But it’s so good there.”

“It’s a lot better than it used to be, sure. But it took decades. And millions of people died in the process.”

A couple of months after I left Afghanistan, the Taliban sacked the town of Kunduz, and the Obama administration announced that the remaining American troops would stay after all.

The Hazara man told me not to go the old citadel walls.

“You have to go through the local neighbourhood to get there,” he said, “and you really shouldn’t. Look,” he pleaded, “when they kidnap a foreigner, the first thing they do is shoot the driver.”

It seemed impossible to argue with that, so I let the matter drop. At Babur’s Garden, he rushed me past scenes of families enjoying an afternoon outdoors and points of interest like Babur’s sarcophagus, begging me not to take pictures in a public place for fear of drawing attention. “OK? OK?” he kept asking, prompting me to get going.

Later, my expat contact Janhavi told me that it was the Afghan way always to say no, and it was up to the guest to push back and to insist.

“The only time you have to back off is if they say you’ll die,” Janhavi said to me. “That’s when you know they really mean it.”

The young man who worked reception at my hotel also went out of his way to feed me bad information.

I had wanted to make a stop in Bamiyan, where the massive Buddha statues that Xuan Zang described returning from his journey to India in the seventh century once stood. The Taliban dynamited them when they were in power. But the empty niches carved into the mountains still looked over the land, judgmental of man’s folly.

Overland travel there was too dangerous now. How about flying?

“The airport in Bamiyan is closed,” the young man told me. For one day I believed him with disappointment. Then I inquired with travel agents. Uniformly they said that this was crazy talk. But there were only two flights a week, and the next flight by now was fully booked.

I came back to the hotel angry with the misinformation. “No, it is closed, I swear,” he doubled down.

I asked for a car to take me to the Kabul Museum. “The museum is closed today,” he said, “holiday.”

It was a Friday, the Muslim holy day. But I had been given no uncertain advice that the museum was open on Friday mornings.

A hoarding commemorating slain Afghan military commander General Massoud in Mazar. Photo: William Han

A hoarding commemorating slain Afghan military commander General Massoud in Mazar. Photo: William Han

I asked him if he could confirm by phone.

“No, this is Afghanistan, you cannot call. They don’t have phones.”

“The museum has no phones?”

“No phones.”

“Does it have a website that you can check?” I asked.

“No.”

“Let me Google that for you.” The museum website had a phone number on it and operating hours. “See, it’s open.”

He turned angry, as though he were the schoolmaster and I some unruly pupil who had disputed his authority. “You should have come to me with this information earlier.”

“It’s your job to give me information!” I bellowed with exasperation.

I began to sympathise with Gan Ying on a new level: when he reached the Persian Gulf, confronted with water, he asked the local fishermen for directions to Rome.

They told him to sail around the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt, and that the voyage would take three years, when obviously the direct route would have been via Mesopotamia to the Levant, which at the time was a Roman province.

Even more incredibly, the Persians told him that female demons haunted the seas, singing songs to sailors so that they forgot their homelands – i.e., the Sirens from Homer’s Odyssey. The tale ended up in China’s imperial annals as reported by Gan Ying.

These same Persians, I thought, could easily be the ancestors of my pathological-liar hotel receptionist.

But it made sense for the hotel staff to discourage its guests from going outside. The message was always the same: you are wearing our armour, and if you ever take it off, you’ll probably die.

Two Afghan women in the lobby overheard me asking about Bamiyan. The woman in her 20s was a lawyer, and the middle-aged woman a judge. I said I was a lawyer as well.

The women asked why I wanted to go to Bamiyan. “I think,” the judge said, “if Daesh catch you, they kill you.” They both laughed. High-pitched, grating laughs, laughs with their incisors. That contempt for the ridiculous in their eyes.

“What do you do if Daesh got you?”

I shrugged and turned up my palms. They laughed some more.

No comments:

Post a Comment