By Layne Vandenberg and Rex Simons

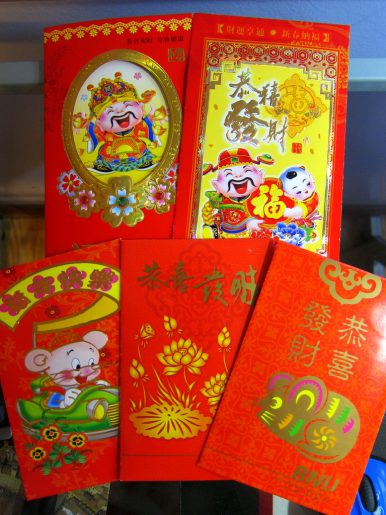

On Tuesday, China and other parts of Asia will celebrate the Lunar New Year with traditions ranging from the simple — hanging red banners around homes and offices — to the completely over the top, including the lion dances depicted in movies and TV. For many around the world, one tradition comes to mind above all others: the red envelope, or hongbao.

On Tuesday, China and other parts of Asia will celebrate the Lunar New Year with traditions ranging from the simple — hanging red banners around homes and offices — to the completely over the top, including the lion dances depicted in movies and TV. For many around the world, one tradition comes to mind above all others: the red envelope, or hongbao.

While there is no single origin story for the tradition of hongbao, two common narratives trace the practice’s history back to the Song or Qin dynasties in China. According to legends from the Song (960-1279 CE), a village in China was terrorized by a demon that no warrior nor statesman could defeat. A young orphan, armed with a magical sword inherited from his ancestors, volunteered to battle the demon and eventually defeated it. The elders from the village rewarded the orphan with a red pouch (envelope) filled with coins to thank him for his courage and bravery.

During the Qin Dynasty (221 to 206 BCE), the elderly would thread coins using red string in a practice that was referred to as “money to ward off evil spirits,” or yasuiqian. It was believed that such money could protect the children from an evil spirit named Sui. As the printing press became more common throughout China, the string of coins was replaced by the red envelope. The name of such monetary gifts also underwent a slight change as well, with the character sui 祟 (referring to evil spirits) replaced by its homophone sui 岁 (meaning years of age, or by extension old age). When children in China today receive yasuiqian from their elders, it carries the connotation of warding off the effects of old age, rather than defeating an evil demon.

Currently, red envelopes are usually given by married couples to single people, regardless of their age, and from elders to young people, normally under the age of 25 or those without jobs. In the office, bosses will usually provide red envelopes out of their own pockets to employees as a gesture for good luck and fortune in the upcoming year. Hongbao are also often given at weddings and birthdays.

Tradition in China also dictates the amount given with each red envelope, with even-number amounts preferred over odd. The number four is avoided in particular as its pronunciation in Mandarin Chinese is homophonous to that of death. The practice of giving red envelopes has also spread throughout Asia, particularly to countries with large ethnic Chinese populations such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia. The concept of a celebratory envelope is not unique to China; Korea also has its own traditions on giving money around certain holidays, including Seollal, the Korean Lunar New Year.

For many foreigners, the first experience receiving or giving a hongbao only occurs abroad in Asia. Rex Simons, an American expat in China, experienced his first true New Year hongbao as a host of a travel show for China’s CCTV, where he celebrated Chinese traditions with a fake family. The episode followed Rex as he painstakingly prepared the correct envelopes with the correct characters, filled them with the correct amount of RMB, and gave them to a “friend’s” son as a form of yasuiqian. Even though traditional red envelopes were exchanged, the end of the episode finds Rex racing with the family to try and see how many digital hongbao they can collect in an example of yet another digital modernization in Chinese society.

In 2014, red envelopes underwent yet another round of modernization as Tencent, a major Chinese conglomerate and the creator of the messaging platform WeChat, introduced digital hongbao through its mobile payment platform. A few years later, analysts estimated that more than 768 million people used WeChat’s digital hongbao feature in 2018, with the average user sending out dozens or even thousands of red envelopes to their friends and family. Tencent has also recently experienced competition from other major Chinese technology firms, including Alibaba and Baidu, to see who will lead the year’s digital red envelope race. In 2019 so far, Baidu reportedly prepared a record 1.9 billion RMB (approximately $231 million) worth of red envelopes by becoming the exclusive partner of CCTV’s annual Spring Festival Gala, the single most watched television broadcast in the world. The arms race between technology companies has put the red envelope on the global map, with millions expected to be sent during Lunar New Year 2019.

Hongbao now represent another example of China’s switch to digital payments. WeChat delivers an abundance of services that similar apps, including its closest Western equivalent WhatsApp, do not provide. Using WeChat, users can not only message, call, and video chat, but they can also top up mobile data, post to an Instagram-esque social media platform (called “Moments”), and manage a WeChat “Wallet.” WeChat’s Wallet function allows users to transfer money without fees, pay for goods and services anywhere using WeChat QR codes, and even book flights, trains, and movie tickets. The ubiquitous presence of WeChat and Alibaba QR codes in shops in mainland China constitutes a large part of China’s growing cashless society.

Hongbao have followed suit. Within WeChat, users can click a virtual red envelope icon, add a message, and then input the amount of Chinese yuan to be digitally sent to other users or into group chats. The digital hongbao will appear as a red envelope icon in the chat, without any indication of the amount sent by the sender. If a hongbao is sent one-to-one between two users, the recipient is unable to tell the amount of the hongbao until they click and “open” the envelope to receive their gift.

If the hongbao is sent to a group chat, the sender still indicates the total amount to be sent; however, the opening of the hongbao becomes a game among the recipients. Whichever recipient “opens” the hongbao first receives the largest share of the amount sent; the second, a slightly lesser amount; and so on until the money has been exhausted. The last users to open the hongbao will most likely receive a notice that the hongbao has already been claimed. This leads to a mad dash in many group chats around the Lunar New Year, with friends who are physically sitting in the same room sending each other hongbao via WeChat to see who can click for the largest amount. Among the younger generations, whose mobile experiences are largely dictated by WeChat, digital hongbao are now the casual norm, with traditional giving a more formal practice.

The digitalization of giving has extended beyond hongbao specifically for the Lunar New Year. Chinese brides have been pictured wearing QR codes at weddings, capitalizing on the almost identical utility of two WeChat payment options: the “transfer” and a “red envelope.” While both ultimately send money virtually, there is societal distinction and acceptance of the subtle difference between a WeChat “transfer” — to transfer money between two users — and a WeChat hongbao — to gift money between any number of users. Unlike money transfers that allow the recipient to see the amount sent before formally accepting the transfer, clicking a WeChat hongbao automatically accepts the gift and deposits the gift into your WeChat wallet. By dressing up a typical money transfer as an envelope with a surprise amount, WeChat created an alternative to tradition that still makes it difficult for recipients to refuse the gift.

The advent of digital red envelopes on WeChat and other platforms does not mean the tradition of red envelopes is disappearing from the Lunar New Year or from Chinese society. Rather, the digitalization of the symbolic hongbao represents an adaptation of Chinese tradition to modern Chinese society. Although young people may rarely encounter hongbao in their physical form, their virtual eternalization preserves the tradition, albeit in a new way.

No comments:

Post a Comment