by Doug Bandow

Richard Nixon famously “went to China” in 1971, ending the hostile silence between the two governments. But Jimmy Carter completed the bilateral relationship, formally recognizing the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Official relations were established on January 1, 1979.

Richard Nixon famously “went to China” in 1971, ending the hostile silence between the two governments. But Jimmy Carter completed the bilateral relationship, formally recognizing the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Official relations were established on January 1, 1979.

The move was controversial, at least to conservatives who backed the Republic of China (ROC), Chiang Kai-shek’s rump state located on the island of Taiwan. The ROC matched the PRC in claiming to be the legitimate government of all China, but without the slightest chance of fulfilling that ambition. After the Nixon trip, Taipei lost not only its seat on the United Nations Security Council but also its membership in the UN. Numerous nations switched their recognition to Beijing. America’s 1979 flip left only a gaggle of smaller states behind Taiwan, many of which have since defected.

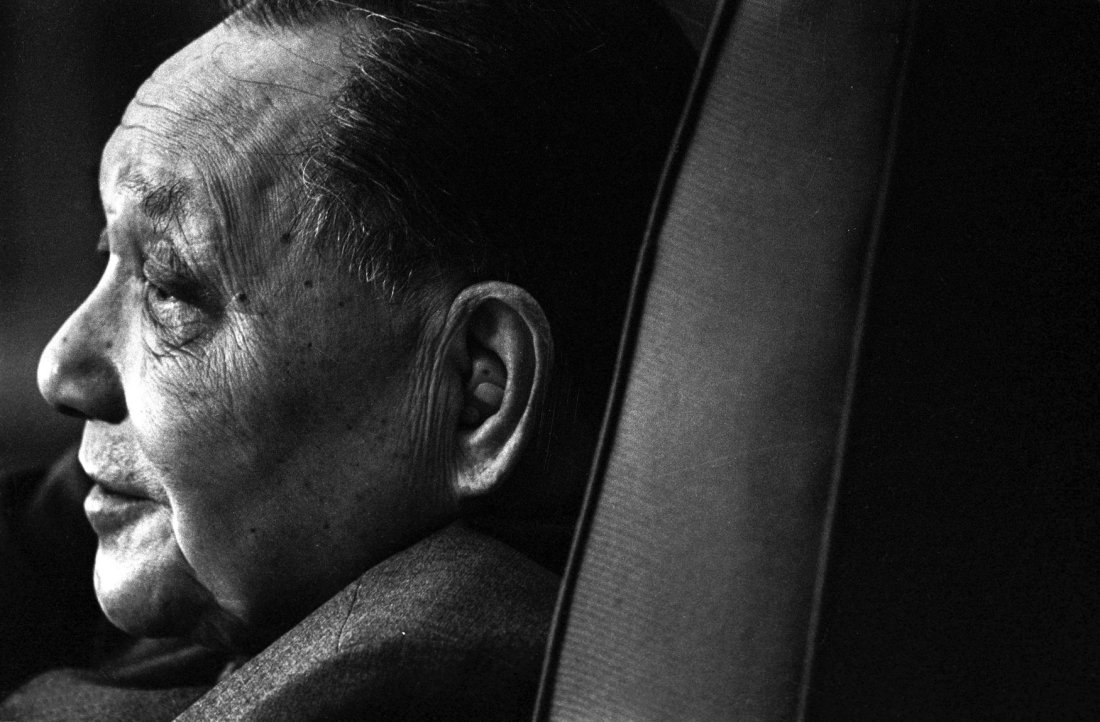

Four decades ago the PRC’s potential was obvious but seemed far more limited and distant. Mao was little more than two years in his grave. The so-called Gang of Four—radicals who supported the violent Cultural Revolution—had been arrested but not yet tried. Deng Xiaoping had been in power little more than a year and economic reforms had barely begun. Recognition was an uncertain investment in the future.

Even a decade or so later, when I first visited the mainland, the PRC still was markedly poor. Even in Beijing and Shanghai, the roads were filled with bicycles and scooters. There were some new buildings, but no one would imagine Beijing challenging America for global leadership. The “China threat,” as it were, seemed very modest.

Fast forward to January 1, 2019. The United States remains ahead economically, but using purchasing power parity instead of exchange rates puts Beijing in first place. The PRC still lags America in military spending but is number two in the world. Even before President Donald Trump’s misdirected global assault on free trade, China was the world’s greatest trading nation, far outdistancing America in Asia. Beijing is using its economic clout to gain political influence through the “Belt and Road” infrastructure investment program.

The good news is that hundreds of millions of people have escaped immiserating poverty. The Chinese also are largely free to work, marry, travel, study, and much more. The deadening personal uniformity and political conformity under the “Red Emperor” is gone. The Chinese people enjoy a degree of individual autonomy and liberty unknown to most of their ancestors.

However, the bad news is extremely bad. Although the Trump administration can be faulted for its tariff tactics, the PRC has manipulated trade and investment rules, stolen intellectual property, targeted foreign firms, and forced technology transfers. Such practices are ever less tolerable as China grows wealthier and more assertive.

Worse, Beijing appears to be racing back to its ignoble past. Xi has eliminated the two-term limit on the PRC president—a limit that was imposed to discourage the rise of another Mao. Under Xi censorship has been intensified, Western contacts have been limited, dissent has been targeted, human rights have been restricted, religious believers have been persecuted, political education has been recreated, and economic reform has been stifled. A million or more Muslim Uighurs have been placed in re-education camps. The Xi government has increased pressure on both Taiwan, which retains de facto independent, and Hong Kong, which retains many British liberties despite its return to PRC control in 1997.

Moreover, Beijing has become more aggressive in pressing its territorial claims throughout East Asian waters. Were the PRC’s claims to the Paracel, Spratly, and Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands accepted, the entire region would be a Chinese lake. The Xi government has abandoned its earlier strategy of “peaceful rise” and used its growing military to press for international concessions. One objective of the Belt and Road plan is to create and access facilities with military value.

Overall, this is a very different China than the one of January 1979. Or the one envisioned when diplomatic relations were established.

The problem is not that economic liberalization and prosperity did not create important pressures for a freer society. Personal autonomy greatly expanded. Employment opportunities and economic choices multiplied. Freedom to worship expanded. Space opened for intellectual debate and voices were heard in favor of institutionalizing the rule of law and more. Young, educated Chinese criticized censorship and dictatorship. The problem is such gains were not institutionalized, and have been dramatically rolled back by a competent and committed authoritarian—in this case, Xi Jinping—who is now serving his second term as president.

Xi is the most powerful Chinese leader since Deng and perhaps Mao. Still, whether he is at the summit or on the precipice—or both simultaneously—is unclear. In fact, the ongoing economic slowdown and the negative impact of the Trump trade war have spurred barely muffled dissent in official circles. However, in the short-term, at least, Xi faces no obvious challenge. So the regime continues to channel its increasing power into very ill pursuits.

What to do?

The United States and friendly states, most notably the Europeans and East Asian democracies, should cooperate and adopt a broadly uniform approach to the PRC. On economics, they should press Beijing to live up to non-discriminatory economic rules. The issue is not the trade deficit, but the use of access to Western markets to advantage Chinese concerns and especially the Chinese state. President Trump’s tactics so far have been maladroit, and his rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership extremely foolish, but Washington got China’s attention.

Little can be done directly on human rights, since no government willingly yields power to its opponents, but democratic states, led by America, should regularly raise the issue and emphasize that Chinese international leadership will be stunted so long as it imprisons people for seeking to influence their own government and make decisions over their own lives. Washington should aid efforts to improve Chinese access to information and break through China’s great firewall. The West should point out that historically war on religion ensures increased social instability since it pushes believers into active opposition. Mass repression of the sort practiced in Xinjiang against Muslims should face broad, sustained criticism. Major powers should warn that enhanced restrictions in Hong Kong raise questions as to Beijing’s willingness to live up to solemn commitments made to other nations.

Dealing with the security aspect of the PRC’s challenge may be the most difficult. The frictions between rising and falling powers, famously termed the Thucydides Trap, are well-known. The United States should not overreact to China’s rise: America remains much wealthier than China. Beijing also faces significant obstacles to becoming a superpower. For instance, the long-time one child policy badly distorted China’s demography; the country may grow old before it grows rich. Moreover, growth has slowed and political mismanagement of the economy has created a commercial minefield including inefficient state enterprises, heavy indebted government firms, bank bad loans, property bubbles, “ghost” cities, politically-motivated regulation, and fake economic statistics.

Indeed, Beijing is not and will not be, at least in the foreseeable future, in a position to threaten the United States. The American military’s lead is significant and its ability to deter attack is overwhelming. The real struggle between the two nations is over Washington’s dominance of East Asia. That is possible only so long as the PRC is weak and America is willing to spend lavishly to project power.

China has far to go militarily but has an equal incentive to strengthen its armed forces. Imagine a world in which the Chinese navy patrolled America’s east coast and the Caribbean, the PRC lectured America on policy toward Cuba, and the potential of war with the United States was routinely discussed in Beijing. Few Americans would passively acquiesce to China’s dominance.

Today Americans are unlikely to sacrifice what is necessary to defeat the PRC in its own neighborhood. After all, it costs far more to build and man a carrier and supporting vessels than a missile or submarine to sink it. The United States faces annual deficits of a trillion-plus dollars and fiscal pressures will explode as the baby boom generation continues to retire. Who will want to sacrifice their Social Security and Medicare benefits to protect Taiwan?

Washington should emphasize the importance of friendly democratic states investing in their own defense, creating militaries capable of deterring China from aggressive action. The goal is not to defeat the People’s Liberation Army, but to make the cost of any attack too great. America also should encourage nations, such as Japan and India, to take on greater regional responsibilities. Rather than jealously safeguard its dominant role, Washington should indicate its willingness to share influence.

America also should stop pushing Russia and China together. Successive U.S. administrations have adopted policies—such as the expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the dismantlement of Serbia, and encouraging color revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine—that are seen as threatening in Moscow. Whatever America’s intentions, Russia could not easily ignore American policy. Imagine the Soviet Union staging a coup against a democratically elected Mexican government and inviting Mexico to join the Warsaw Pact. Officials in Washington would not be amused.

Although China and Russia have very different interests, the two have drawn together in response to U.S. pressure. Washington and Brussels should pursue a diplomatic modus vivendi with the Putin government. They would drop NATO membership for Georgia and Ukraine and revoke economic sanctions in return for Russia halting support for separatists, ending harassment of Kiev, and stopping interference in American and European elections. The West would informally accept but not formally recognize Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Moscow then could see its future with the West. That would tip the international balance a bit more against an aggressive China.

The most important objective should be to avoid conflict between the two governments. In the nineteenth century, Great Britain faced two rising powers. It accommodated one, America, and confronted the other, Germany. Out of the first grew a warm partnership. Out of the second developed two global wars. It is obvious which example the United States should follow.

No comments:

Post a Comment