In recent months, Germany, France, Britain, the European Union, Australia, Japan and Canada have all joined an unprecedented global backlash against Chinese capital, citing national security concerns. Dealmakers now wonder whether this dynamic will run its course or should be taken as a new normal.

In recent months, Germany, France, Britain, the European Union, Australia, Japan and Canada have all joined an unprecedented global backlash against Chinese capital, citing national security concerns. Dealmakers now wonder whether this dynamic will run its course or should be taken as a new normal.

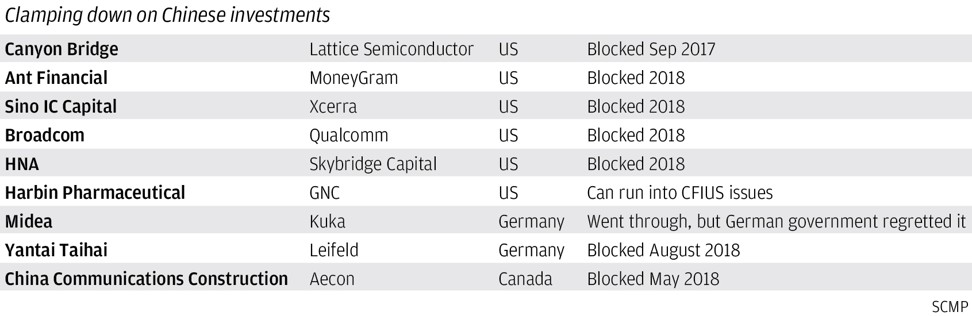

Outside the US, Chinese acquisitions have increasingly run into trouble. In August, the German government for the first time vetoed a Chinese takeover – the nuclear equipment maker Yantai Taihai’s proposed acquisition of Leifeld Metal Spinning, which specialises in manufacturing for Germany’s aerospace and nuclear industries – on national security grounds.

In May, Canada blocked a proposed takeover of the construction firm Aecon by a unit of China Communications Construction, also invoking national security reasons.

As a result, China’s outbound direct investment dropped globally for the first time since 2002, to US$124.6 billion, from a peak of US$196.15 billion as recently as 2016, according to data compiled by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

“The movement we are seeing around the world is an expression of calls for wariness about Chinese investments, especially in technology,” said Jeremy Zucker, co-head of the international trade practice at the law firm Dechert in Washington. “And it was sharpened and accelerated by the Trump administration.”

One big trigger, Zucker said, was China’s public vow to dominate high technology in the next seven years, a programme known as “Made in China 2025”. “When the Western world heard this, it sounded like a declaration of war,” he said.

The resistance comes as US complaints about China – and its insistence that China was using investments to acquire critical infrastructure technologies – grow louder.

The US has always subjected foreign acquisitions in sensitive industries to tough review. But the present administration has taken it to a new level, and made it a focus in its disputes against China’s trade practices.

Since Donald Trump became US president in 2017, he has repeatedly described China as an unfair player in trade and his administration has blocked a number of proposed Chinese acquisitions.

The hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of deals shot down this year alone on national security concerns included HNA’s bid for Skybridge Capital, a hedge fund founded by Trump’s one-time communications director Anthony Scaramucci; the US$580 million purchase of US semiconductor company Xcerra by a Chinese investment firm backed by state-owned Sino IC Capital; and the US$117 billion takeover of the semiconductor equipment maker Qualcomm by Broadcom, a Singapore-based company with close ties to Beijing.

The drop in Chinese investment in the US has been severe. In the first half of this year, Chinese companies invested just US$1.8 billion, a plunge of more than 90 per cent from the year earlier and the lowest level in seven years, according to investment consultancy Rhodium Group.

The drop in Chinese investment in the US has been severe. In the first half of this year, Chinese companies invested just US$1.8 billion, a plunge of more than 90 per cent from the year earlier and the lowest level in seven years, according to investment consultancy Rhodium Group.

Last month, Trump signed legislation that expanded the powers of the 43-year-old inter-agency Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS).

Under the new law, the range of deals the committee can review for national security concerns grew to include transactions in which a foreign investment was merely a minority interest, instead of a controlling share; and extended review powers into the real estate sector that previously had not been part of its portfolio. In the legislation, Congress encouraged other countries to adopt CFIUS-like reviews of Chinese investment.

“The wave took off because the US reached out to other governments. That led to other CFIUS-like entities to emerge around the world,” said Mario Mancuso, a US undersecretary of commerce in the George W. Bush administration.

From Canada to Mexico to the European Union, other nations are having their own problems dealing with the Trump administration. Even so, governments outside the US are in agreement about what they perceive as the threat from China, which is accused of using investments and merger deals to steal technologies and gain access to sensitive data that could endanger national security.

“History repeats itself in a way. During the cold war, there were concerns about the internet. Right now, it’s the fear about technology,” said Christopher Griner, chairman of the national security and CFIUS practice at the Washington office of the Stroock & Stroock & Lavan law firm.

Germany started drafting its legislation after a number of high-profile takeovers by Chinese buyers, including a 2016 US$5 billion purchase of Kuka, Germany’s most advanced robotics manufacturer, by Chinese appliance maker Midea.

Concerned about China’s growing appetite for its most advanced technologies, Germany last year changed its laws to improve the government’s ability to block acquisitions of stakes as small as 25 per cent stake in “critical infrastructure” industries.

Just last month, the Chinese nuclear equipment manufacturer Yantai Taihai dropped its bid for the German metal tool maker Leifeld, a key company for Germany’s nuclear power industry. Berlin had hinted that it was prepared to use its new power to veto takeovers.

“It’s the first time Germany has used its veto power in such a way, and that could have a ‘snowball effect’ across Europe,” a China-based news publication Caixin Global quoted an analyst as saying at the time.

Also last year, Germany joined France and Italy in calling for a Europe-wide mechanism for more rigorous review of foreign takeovers. The move was seen as a response to rising worries about transferring so-called dual-use technologies to China through investments.

Britain, which was one of the most welcoming nations towards Chinese investment under former prime minister David Cameron, is now following the lead of the US, Germany and France and expanding its regulatory entity into a separate unit, like CFIUS.

Britain, which was one of the most welcoming nations towards Chinese investment under former prime minister David Cameron, is now following the lead of the US, Germany and France and expanding its regulatory entity into a separate unit, like CFIUS.

Britain used to operate under a much looser approach to sensitive deals. Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, for example, won a key contract with the leading British telecom provider BT 13 years ago.

In July, Britain released a National Security and Investment White Paper, which aimed to improve the government’s powers to block foreign acquisitions of British assets that are deemed national security sensitive.

Government ministers were frustrated late last year when they failed to block the purchase of British chipmaker Imagination Technologies by Chinese fund Canyon Bridge, which is owned by state-owned Yitai Capital. The deal went through weeks after the Trump administration blocked Canyon from buying the US chip maker Lattice Semiconductor.

Under the new proposal, the British government expects to review as many as 50 proposed foreign deals a year for national security concerns. In each of the last two years it reviewed just one.

The new proposal also eliminates a previous requirement that a deal involve a target with at least £70 million (US$91 million) in annual revenue to trigger a review. Now the government can effectively review any deal, regardless of the size.

The new proposal also eliminates a previous requirement that a deal involve a target with at least £70 million (US$91 million) in annual revenue to trigger a review. Now the government can effectively review any deal, regardless of the size.

In April, a British watchdog agency notified government agencies not to do any further business with the Chinese telecoms equipment maker ZTE, in tandem with the US blocking ZTE from buying American components for seven years. The US wound up retreating from its stand, but there are no indications that Britain has changed its position.

As trade tensions between the US and China continue to escalate, with Trump soon to impose tariffs on an additional US$200 billion of Chinese imports, Chinese deals for US tech companies are likely to be harder to come by. And other Western nations no longer provide an easy alternative.

“Down the road, Chinese money will probably find a way to come out – and the world knows it needs China money,” said Edward Mermelstein, a foreign investment adviser based in New York. “But right now, protectionism is on the rise and it’s not just in the US.”

No comments:

Post a Comment