Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang say the US should not take China’s talk of a ‘peaceful rise’ at face value, but must work with allies to move China towards international norms, rather than contain it

Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang say the US should not take China’s talk of a ‘peaceful rise’ at face value, but must work with allies to move China towards international norms, rather than contain it

The communique reveals a subtler “grand plan” of China. The Taiwan issue is simply one step in Beijing’s larger strategic goal of pushing the United States and its influence out of the Indo-Pacific region.

However, this strategic endgame cannot be achieved without the support of other objectives such as the Belt and Road Initiative and establishing control over the East and South China seas. Each of these objectives must be understood within the geopolitics of the regional balance of power through the US-led security dialogue also involving Japan, Australia and India, a grouping commonly known as the Quad.

China’s priority begins with the Communist Party of China and its legitimacy. Because China’s strategic objectives are predicated on this legitimacy, the party must provide economic and social stability for its citizens, which requires an uninterrupted supply of energy to not only deliver economic growth but also sustain military operations. It is no surprise that given China’s economic challenges, Beijing has called for stability in six key areas, including employment and finance.

China’s primary objective of defending territorial integrity begins with Taiwan. For China, Taiwan is not merely a runaway province, it is a focal point in the first island chain that would allow China to project power out to the Western Pacific and the second island chain. This is generally referred to as Anti Access/Area Denial.

Hence, the formation of the air defence identification zone in the East China Sea and the island-reclamation, followed by military build-up, in the Spratly and Parcel islandsin the South China Sea are not only meant to claim de facto rights to the resources within the nine-dash-line, they are also tactical steps towards employing coercive diplomacy with its neighbours, and establishing operational control over the region in its move towards unification with Taiwan. China is also working diplomatically to “peel” away those countries that currently recognise Taiwan.

A separate but related issue is that China believes it still has some unfinished business with Japan – both with respect to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, as well as in the broader historical context of national humiliation. It is why there is speculation China’s first indigenously built aircraft carrier will be called the “Shandong”, a province once ceded to Japan after first world war.

The key enabler to project its power has been China’s explosive economic growth. As it cools down, however, major programmes such as the belt and road strategy will be critical to any future projection of power. The stated purpose of the initiative is to promote regional economic cooperation and promote peace and development. However, there are other hidden motivations.

First, China wants to decrease the dependence on its domestic infrastructure investment and begin moving overseas to address the overcapacity within China. The key instrument of this investment transfer comes with the Chinese system of state capitalism.

Second, China wants to internationalise the use of its currency through the belt and road. Making the renminbi a global currency had been one of highest economic priorities of Beijing’s Grand Plan.

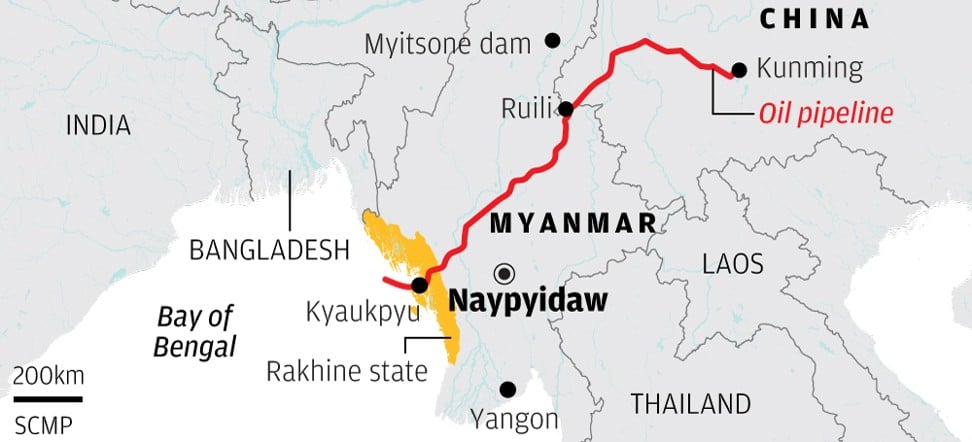

Third, China seeks to secure its energy resources through new pipelines in Central Asia, Russia and South and Southeast Asia’s deepwater ports. The Beijing leadership has been concerned about the “Malacca dilemma”, a term coined by former president Hu Jintao, who voiced fears that “certain major powers” might control the Malacca Strait and who said China needed to adopt “new strategies to mitigate the perceived vulnerability”.

Thus, belt and road projects – such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Kyaukpyu pipeline in Myanmar that runs to Yunnan province, and the ongoing discussions for the proposed Kra Canal in Thailand – are of vital interest to China because they would provide alternative routes for energy resources from the Middle East that bypass the Malacca Strait.

The continuing tensions with China have bolstered the Quad. Each of the Quad members has its own economic and geostrategic concerns over balancing China’s expanding power and influence with a host of counter-strategies. They are hardly a “containment policy” but collectively a range of constraint devices. US President Donald Trump has, for example, signed into law the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act, which is belatedly an expression of America’s commitment to the security and stability of the region.

The US Congress has also passed the Better Utilisation of Investments Leading to Development (Build) Act to reform and improve overseas private financing to help developing countries. It is also aimed at countering China’s influence and offering belt and road countries alternatives to what has been called China’s “debt trap” diplomacy.

China now seeks to create a new set of global norms, while overturning the existing norms that Beijing claims to have had no role in creating. That may be true; however, China should remember that the prevailing norms have also played a critical role in China’s rise.

Whatever claims China has made to a “peaceful rise”, it is clear that “peaceful” rings hollow. Yet, American policies must not embark on a fool’s errand to “contain China”. Rather, the US should continue to engage allies and friends to maintain a consistent and persistent presence as an American pledge for unity, security and peace.

Whatever claims China has made to a “peaceful rise”, it is clear that “peaceful” rings hollow. Yet, American policies must not embark on a fool’s errand to “contain China”. Rather, the US should continue to engage allies and friends to maintain a consistent and persistent presence as an American pledge for unity, security and peace.

In addition, the US and its allies should apply a unified front in pressuring China and engaging Beijing to respect global norms in areas such as trade, intellectual property and cybersecurity.

In all, China should measure its ideological priorities against its costs. If and when China and Taiwan unite, it will be based upon a mutual amity and belief that it is in the interest of all Chinese people to do so – not through coercion and aggression. Beijing cannot bend history to its will.

No comments:

Post a Comment