By Dan De Luce, Mushtaq Yusufzai, Courtney Kube and Josh Lederman

Aware Trump has expressed impatience with the U.S. mission in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad has moved quickly to get the Taliban to the negotiating table.

Aware Trump has expressed impatience with the U.S. mission in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad has moved quickly to get the Taliban to the negotiating table.

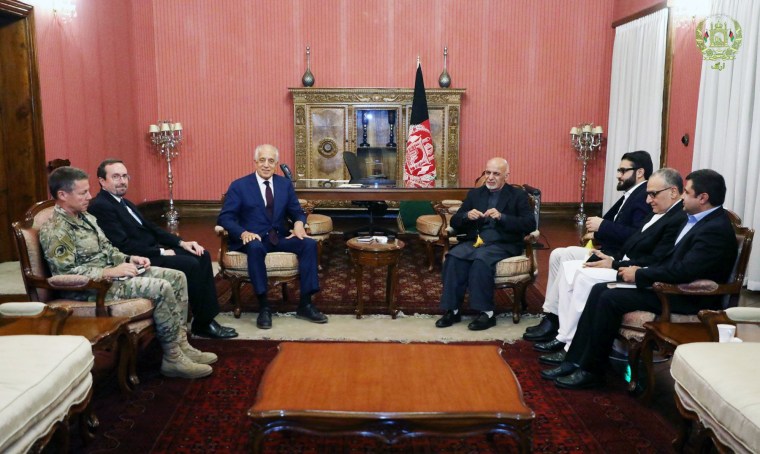

Afghanistan's President Ashraf Ghani, seated right, and U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, meet in Kabul on Nov. 10, 2018.Presidential Palace / Reuters

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump's envoy to Afghanistan is reaching out to many top Taliban figures as he tries to launch peace negotiations to end the war before Trump can simply pull the plugand order U.S. troops home, say foreign diplomats.

U.S. special envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has moved at a rapid pace and ventured beyond the official Taliban office in Qatar to meet other members of the insurgency, two foreign diplomats and three former U.S. officials told NBC News.

His outreach included a meeting in the United Arab Emirates with a militant claiming to be an associate of Mullah Yaqub, son of late Taliban leader Mullah Omar and now one of two deputies to the current Taliban leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, two foreign diplomats said.

Khalilzad is "testing all channels," said one Western diplomat, who was not authorized to speak on the record.

Although it remained unclear if the Taliban member was indeed a representative sent by Yaqub, the meeting reflected how Khalilzad is moving with a sense of urgency and casting a wide net to try to persuade different elements of the insurgency to come to the table to talk peace, former officials said.

Keenly aware that President Trump has expressed impatience with the U.S. military mission in Afghanistan and that time is limited, Khalilzad, who was born in Afghanistan and served as U.S. ambassador to the country after the 9/11 attacks, has pressed ahead with his diplomacy at a swift tempo, former officials and foreign diplomats said.

U.S. officials are operating under the assumption that the president will pull the plug on the current American military mission in Afghanistan well before the U.S. presidential election in November 2020, current and former U.S. officials said.

"Both the Defense Department and State Department are acting as if withdrawal is on the table, sooner or later," said Thomas Jocselyn, a senior fellow at the Federation for Defense of Democracies think tank.

The Trump administration has also sought to force the Taliban to the negotiating table with a massive bombing campaign. This year the number of U.S. bombs dropped on Afghanistan has hit a record high, with more than 5,200 as of September 30.

The State Department declined to divulge details of who Khalilzad met during his travels or what was discussed, but said he will continue to meet "with all interested parties."

"We are not going to provide a read-out of every meeting as Special Representative Khalilzad determines how best to promote a negotiated settlement between the Government of Afghanistan and the Taliban," said a State Department spokesperson, Heidi Hattenbach.

She also said the U.S. envoy has stayed in close communication with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and other Afghan political leaders. In his last trip, his first and last stops were in Kabul, "to ensure President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah were kept informed of all his upcoming meetings and the subsequent findings from those meetings."

The recent flurry of U.S. diplomacy — and Trump's clear ambivalence about keeping troops in the country — has created friction with Ghani and his allies. Afghan officials in Kabul fear Washington's direct talks with the Taliban could leave them sidelined and that a short timeline could backfire badly.

"Peace talks also must not be driven by superficial deadlines urged by a U.S. administration anxious to be done with the conflict," Nader Nadery, a former senior adviser to President Ghani, wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post Monday.

The recent meeting with a representative of the son of the Taliban's former leader, if confirmed, would be "a potentially positive development" given Yaqub's senior rank and his reputation for favoring a political settlement, said Johnny Walsh, a former lead adviser on Afghan peace efforts at the State Department. U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, talks with local reporters at the U.S. embassy in Kabul on Nov. 18, 2018.U.S Embassy / Reuters

U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, talks with local reporters at the U.S. embassy in Kabul on Nov. 18, 2018.U.S Embassy / Reuters

U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, talks with local reporters at the U.S. embassy in Kabul on Nov. 18, 2018.U.S Embassy / Reuters

U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, talks with local reporters at the U.S. embassy in Kabul on Nov. 18, 2018.U.S Embassy / Reuters

"It's worth exploring more of those proposective channels than perhaps we collectively have in the past, because some of them will lead somewhere," Walsh said.

Yaqub's father, Mullah Omar, was the reclusive founder of the hardline Islamist Taliban that ruled the country from 1996-2001 and forged an alliance with Osama bin Laden and Al-Qaeda. His regime was ousted from power by U.S.-led forces in 2001 for having offered safe haven to Al-Qaeda militants who staged the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington.

In three days of talks in Qatar earlier this month, Khalilzad met with eight Taliban representatives, including two militants formerly held in Guantanamo, Khairullah Khairkhwa, the former Taliban governor of Herat, and Mohammed Fazl, a former Taliban military chief, Taliban sources told NBC News. Their participation signaled the Taliban's serious interest in holding talks and Fazl in particular is seen as boosting the authority of the Taliban negotiating contingent in Qatar, analysts said.

In his recent visit to Kabul, Khalilzad told reporters that "I remain cautiously optimistic or hopeful given the complexities that exist."

The U.S. envoy also said that the "Taliban are saying that they do not believe that they can succeed militarily."

But an insurgency source rejected Khalilzad's comments, saying his account was overly positive and that the group had not given up on its military prospects.

"We only mentioned that we believe that fighting is not the solution to any problem," a senior Taliban leader, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told NBC News.

Khalilzad has asked President Ghani and the Taliban to form negotiating teams, stressing that the delegations need to be broadly representative to ensure a successful settlement, foreign diplomats and former officials said. By moving ahead with a series of direct discussions with the Taliban, Khalilzad is effectively putting pressure on Ghani to form a negotiating team without delay, said former U.S. officials familiar with the talks.

Afghan electoral authorities, meanwhile, have raised the possibility of postponing the presidential election scheduled for April next year due to ballot counting problems in last month's parliamentary polls.

In his Kabul meetings, Khalilzad has explored the idea of pushing back the election and its potential benefit to peace talks, an Afghan government official and a former U.S. official said.Under this scenario, an interim government could include a Taliban representative and this possibly could open the way for the Taliban to enter into full-fledged peace negotiations, as it has long maintained that the existing Afghan government and constitution are illegitimate. Taliban leader Mullah Omar died in 2013.National Counterterrorism Center / Reuters

Taliban leader Mullah Omar died in 2013.National Counterterrorism Center / Reuters

Taliban leader Mullah Omar died in 2013.National Counterterrorism Center / Reuters

Taliban leader Mullah Omar died in 2013.National Counterterrorism Center / Reuters

Khalilzad told reporters in Kabul that it was up to Afghans to decide whether to postpone the elections but he added that it would be ideal to arrive at a peace agreement before the April vote.

Critics have warned that forming an effective interim government could prove impossible given the current Afghan government's deep divisions and frequent dysfunction.

The Afghan official said that Ghani's government is skeptical that the Taliban can deliver on any promises and that Pakistan and other countries that lend support to the insurgents hold the key to any peace deal.

"The Afghan government doesn't think that the Taliban is independent enough to stop the war even if they were to agree to do so in negotiations," the official said. "The only way fighting will stop is if the Pakistanis and other international supporters of the Taliban are involved in the negotiations."

Pakistan — the longtime patron of the Taliban — last month released Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, a co-founder of the insurgency, to allow him to take part in any political talks. The move was seen as a welcome initial step by U.S. officials, but it remained unclear if Islamabad was prepared to throw its full weight behind the talks.

Still, former officials said the current peace effort showed more promise than a previous U.S. attempt under President Barack Obama, which was plagued by turf battles inside the administration and ambivalence among military commanders, who favored hammering the Taliban on the battlefield before entering into any serious talks.

"It was seen as a sort of side project that the State Department was running," said Jason Campbell, a former senior official at the Defense Department who worked on Afghanistan policy.

The whole project collapsed in 2013, with then Afghan President Hamid Karzai feeling betrayed by Washington's outreach to the Taliban.

The current talks with the Taliban have been accompanied by a spike in violence in Afghanistan, amid signs that the Taliban have gained strength on the battlefield in recent months. A suicide bombing last week in Kabul claimed more than 50 lives and three U.S. service members were killed Tuesday by a roadside bomb near Ghazni city. Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanakzai, head of the Taliban's political council in Qatar, and an unidentified representative of the Afghan Taliban movement speak prior to the start of the Second Moscow round of Afghanistan peace settlement talks in Moscow on Nov. 9, 2018. Sergei Chirikov / EPA

Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanakzai, head of the Taliban's political council in Qatar, and an unidentified representative of the Afghan Taliban movement speak prior to the start of the Second Moscow round of Afghanistan peace settlement talks in Moscow on Nov. 9, 2018. Sergei Chirikov / EPA

Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanakzai, head of the Taliban's political council in Qatar, and an unidentified representative of the Afghan Taliban movement speak prior to the start of the Second Moscow round of Afghanistan peace settlement talks in Moscow on Nov. 9, 2018. Sergei Chirikov / EPA

Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanakzai, head of the Taliban's political council in Qatar, and an unidentified representative of the Afghan Taliban movement speak prior to the start of the Second Moscow round of Afghanistan peace settlement talks in Moscow on Nov. 9, 2018. Sergei Chirikov / EPA

In turn, the Pentagon has ramped up a bombing campaign against the Taliban, seeking to keep up military pressure on the insurgents.

As of the end of September, U.S. military aircraft released a record 5,213 weapons over Afghanistan so far this year, surpassing the total for 2017 which stood at 4,361, according to U.S. Central Command.

For their part, the Taliban also have adopted a "fight and talk" strategy, undertaking fresh attacks on towns and cities — including a five-day siege of Ghazni in August — even as their representatives held a series of meetings with U.S. diplomats in Doha.

Analysts and former officials say the Taliban is in a stronger position on the battlefield than at any time since they were ousted from power in 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment