by Michael B. Greenwald

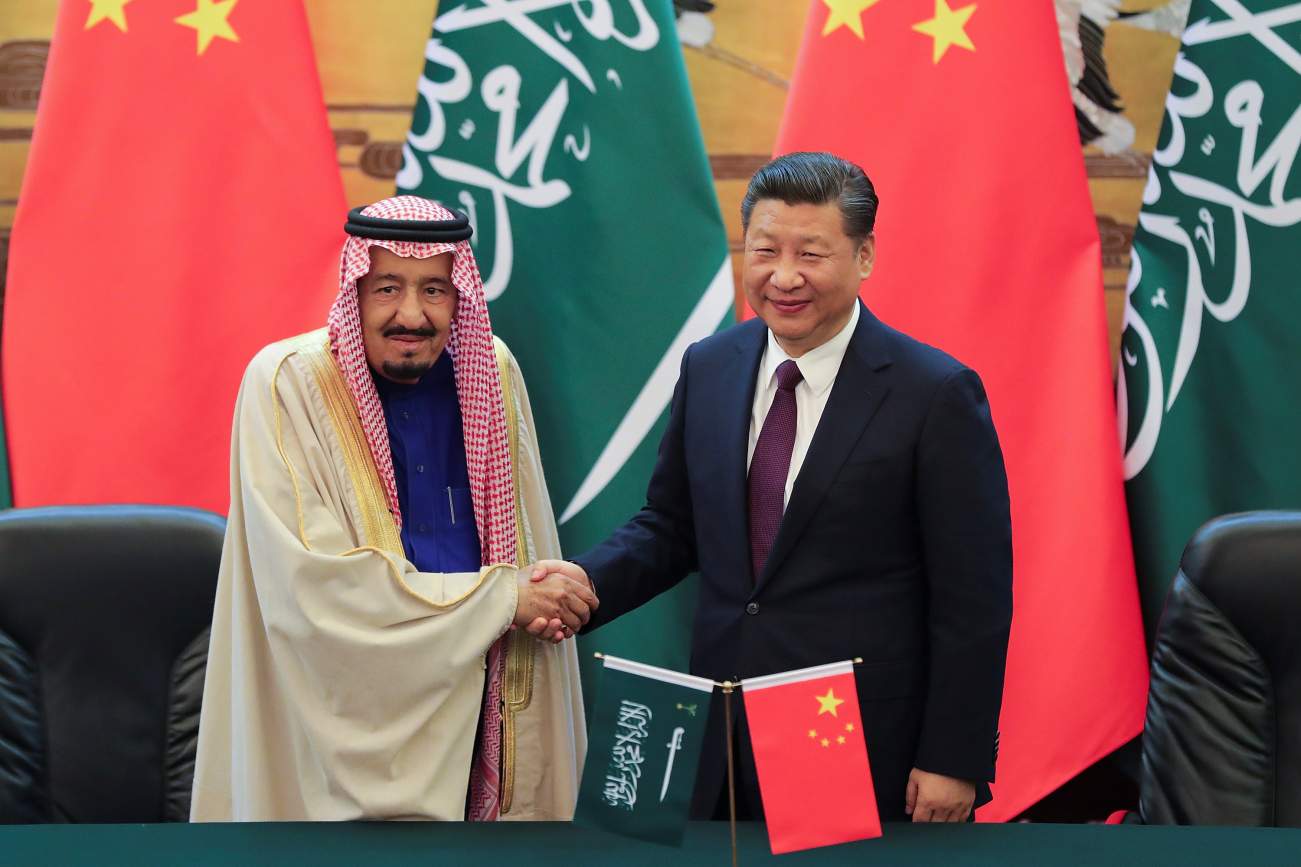

Since the Fracking Revolution, Saudi Arabia has embraced closer energy cooperation with non-Western powers, like China, Russia and India.

Since the Fracking Revolution, Saudi Arabia has embraced closer energy cooperation with non-Western powers, like China, Russia and India.

Since the October death of Jamal Khashoggi, Riyadh’s economic relationships have been the subject of intense international scrutiny. Most major governments have been distancing themselves from Saudi Arabia. In particular, the withdrawals from the Future Investment Initiative (FII) to the German freeze on arms exports, both governments and some in the private sector have been keen on distancing themselves from the country. In recent weeks, strong U.S. Congressional reactions have been discussed, and will soon be at the forefront of the narrative.

That said, Saudi Arabia is far from being isolated on the global economic stage. As Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin withdrew from attending the Future Investment Initiative, the CEO of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund, Kirill Dmitriev, led a delegation of over thirty CEOs. Even in the face of American pressure and increased international scrutiny, prominent American energy firms, like Halliburton and Baker Hughes GE, signed memorandums of understanding with Aramco at the FII, while Saudi tech investment has continued to flow to Silicon Valley startups, like View and Zume. Over the medium term, Saudi growth is expected to recover from its 2017 lows, likely powering more economic shifts in the country.

Since the Fracking Revolution, Saudi Arabia has embraced closer energy cooperation with non-Western powers, like China, Russia and India. In the downstream energy industry, the Saudis have embraced greater investment in the refining and petrochemical sectors. In the 1980s, the Saudis made their first forays into this field through a string of joint ventures (JVs) in the North American market, and are today the owners of the largest refinery in the United States (Port Arthur).

Similarly, Aramco sent its first delegates to China as early as 1989, but reached its first deal much later in 2007. Since then, Aramco has opened several refineries in Liaoning and Zhejiang, and in the future, it could revisit its stalled refinery project in Yunnan. The pace of this deal making has been accelerated by the decline of Saudi market share in the Chinese energy mix, sinking to 13.1 percent in March 2018 from as high as 20 percent in 2013. Having been overtaken by Russia as China’s largest supplier, the Saudis are eager to establish long-term supply contracts in the country and raise Aramco’s international profile.

Aramco has launched projects throughout Asia, including in Maharashtra, India, Johor, Malaysia, and Gwadar, Pakistan. These projects all reflect the dynamics of a new global oil market, as the United States rises among the ranks of global producers.

Since the OPEC+ Production Cut Agreement in 2016, the Saudis and Russians have intertwined their oil policy to better manage supply and demand demographics. Natural gas presents an area of future cooperation, exemplified by the investment in Novatek’s Arctic LNG-2 Project. For the Saudis, this opportunity presents a simple choice: Russian gas allows more oil to be exported, in turn, enabling the country to boost its export revenues.

With the ambitious Vision 2030 goals in mind, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Public Investment Fund has become a much more aggressive investor in the tech industry. So far, this has included a mix of high-profile investments in large startups, like Uber, as well as investment through the joint collaboration with Softbank, the Vision Fund. Even in the aftermath of the Khashoggi killing, Zume and View Inc. have both happily accepted $1.5 billion through the Vision Fund. Outside of the United States, the Saudi-backed Vision Fund has also courted Chinese firms like ZhongAn (insurtech), Bytedance (social media) and Sensetime (facial recognition/AI).

This investment has acted as a two-way street for Riyadh to bring in vital investment and tech transfers at a time of great reforms. A recent Vision Fund-financed startup, Katerra, signed a deal to construct fifty thousand houses in the Kingdom, with much of the manufacturing being sourced locally. Though the Saudis may consider closer cooperation with Chinese tech firms in the future, the existence of deep public and private funds in the country will ensure alternatives exist to Saudi financing. Given that these are not present in the U.S. market, the Saudis have more leverage making tech deals in Silicon Valley than in Shenzhen.

This trend of greater economic diversification presents benefits and costs for sanctions regimes in the short to medium term. In the short term, closer downstream investment in China and India may increase the effectiveness of the maximum pressure campaign by providing a clear alternative to Iranian crude on global markets. At the same time, closer Saudi investment in the Russian energy sector could reduce the effectiveness of Western sanctions in the medium term.

The recent Magnitsky sanctions have escalated what some may have written off as a one-time incident, potentially giving way to more future Congressional escalation. These effects are heavily psychological and will play out over the next several months, but it is important for policymakers in Washington to maintain a broad perspective. With Saudi foreign investment at a fourteen-year low prior to the crisis, Riyadh will need to be careful in its response. An inability to assuage the concerns of international investors could threaten the future viability of the Vision 2030 project, in which Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has invested a significant amount of political capital.

There are also a number of limitations to these evolving partnerships. Future bilateral investment between Riyadh and Beijing is likely to be controversial within the context of the Belt and Road Initiative. Having pledged $6 billion in aid to Pakistan, the Saudis have a first-hand look at the potential downsides of unsustainable infrastructure investment from Beijing. At the same time, cooperation between the Russians and the Saudis may unravel if more American supply floods the market in the near future. The differential between the Russian and Saudi breakeven price- hovering around $40 and $70 respectively—could be the catalyst for a messy divorce in oil markets.

Further, Riyadh’s paramount concern is the evolving geopolitical contest with Iran. In this context, the Saudis need Washington as a reliable partner to counter an ascendant Tehran in the region. Since 2014, Chinese military cooperation with Iran has deepened, including a joint naval exercise in the Strait of Hormuz in June 2017. India’s ambitious port project in Chabahar is a critical investment in the future of Iran, mirroring the large Chinese investment in neighboring Pakistan. The Russians have lent Tehran significant security support through its ground presence in Syria and its 2016 S-300 sale. With these cases in mind, Washington remains a critical long-term security partner for the Saudis, regardless of any economic shifts.

Michael Greenwald is a former United States Treasury attaché to Qatar and Kuwait, and a fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center.

No comments:

Post a Comment