The fourth instalment of a series on China’s hi-tech industry development master plan looks at artificial intelligence (AI) and its promise to lift the country’s industries up the value chain

The fourth instalment of a series on China’s hi-tech industry development master plan looks at artificial intelligence (AI) and its promise to lift the country’s industries up the value chain

But in 2017 an emblem of Western innovation outplayed the Middle Kingdom at literally its own game, when AlphaGo, a computer program from Alphabet's DeepMind Technologies, beat the world’s top player Ke Jie 3-0 in a Sputnik-like moment that spurred China into a concerted, state-directed effort to catch up in artificial intelligence (AI).

Dubbed the fourth industrial revolution, the development of AI encompasses a wide range of technologies that can perform tasks characteristic of human intelligence, such as understanding language and recognising objects. Sometimes described as machine learning, what separates AI from ordinary computer programming is the capacity for machines to correct themselves through trial and error, mimicking the cognitive functions of the human mind.

After many false starts in the 20th century, AI is finally making waves and has captured the attention of policymakers around the world due to concurrent advances in computer power, data collection and theoretical understanding.

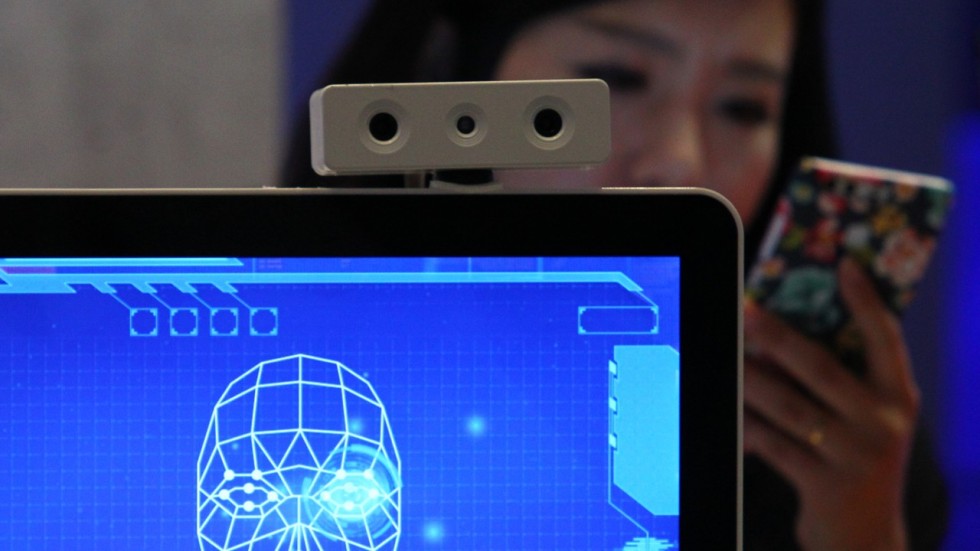

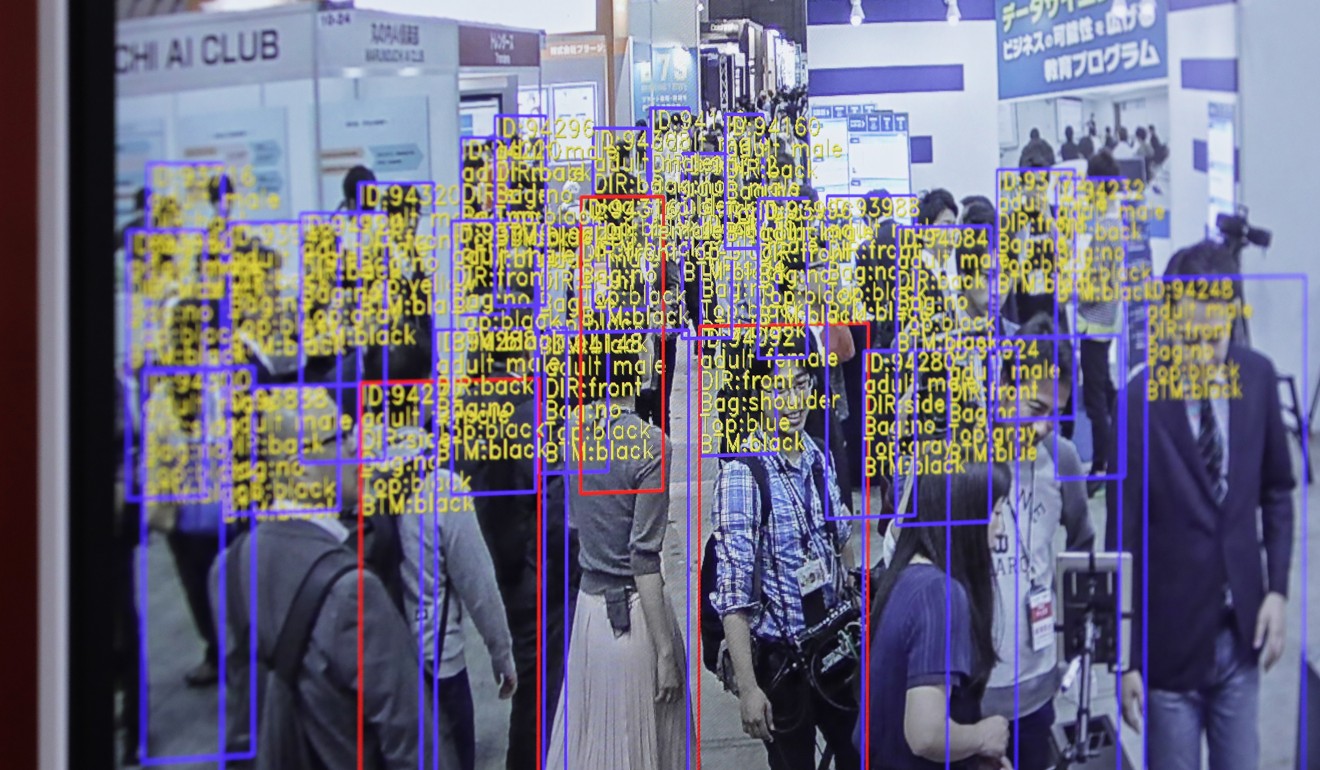

Aside from gaming, the practical applications of AI are huge – from diagnosing serious illnesses like lung cancer using medical imaging, to improving manufacturing processes using sensors and big data, to enhancing security and surveillance at immigration controls at airports using facial recognition technology.

Although the US had a head start, AI has assumed a key role in Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2025’ master plan, which promises to lift the country’s industries – from robotics and aerospace to new materials and new energy vehicles – up the value chain, replacing imports with local products and building global champions able to take on Western giants in cutting-edge technologies.

The process started with the issuance by the State Council in July 2017 of “A Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan”. The three-step road map involves keeping pace with leading AI technologies and applications in general by 2020; then to achieve AI breakthroughs by 2025; and finally to be the world leader in a domestic industry worth US$150 billion by 2030.

Beijing originally appointed four technology leaders – Baidu, Alibaba Group Holding, Tencent Holdings and iFlyTek – as “national champions” to lead the development of innovational platforms in self-driving cars, smart cities, computer vision for medical diagnosis, and voice intelligence, respectively. Alibaba is the owner of the South China Morning Post.

It recently added to its list the Hong Kong start-up SenseTime, which specialises in face- and image-recognition technology, to establish an AI innovational platform for intelligent vision.

But AI development is now embroiled in the wider row over ‘Made in China 2025’, the programme that has become a lightning rod in the escalating trade war between the US and China. Sensing a threat to its global technological dominance, the US has seized on the plan as an example of what it sees as unfair state intervention in China's economy. US President Donald Trump earlier this year convened a gathering of the country’s business elite to discuss the state of AI development.

China has recently tried to play down head-to-head confrontation with the US over AI.

That technology needs to be viewed as an economic game-changer, whose benefits can be shared and potential problems solved globally, Chinese Vice-Premier Liu He told a gathering of AI elites in Shanghai last month at the World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC).

That technology needs to be viewed as an economic game-changer, whose benefits can be shared and potential problems solved globally, Chinese Vice-Premier Liu He told a gathering of AI elites in Shanghai last month at the World Artificial Intelligence Conference (WAIC).

“As members of a global village, I hope countries can show inclusive understanding and respect to each other, deal with the double-sword technologies can bring, and embrace AI together,” said Liu, who has been China’s top trade negotiator in the US-China trade war and is also on the country’s technology development committee.

But is China really biting at the heels of the US as an AI superpower?

An Oxford University study released in March indicates China remains a long way behind the US. China was given a score of 17 for its overall capacity for developing technologies in AI, compared with 33 for the US, its main rival in the global AI race.

The report, from Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, found that except for “access to data”, China trails the US in three core areas of AI growth: hardware, research and algorithm development, and commercialisation of the industry. The biggest obstacle is likely to be production of hardware, like microprocessors and chips, the study found.

Access to large quantities of data, aided by relatively lax privacy protection laws, has been cited as one of China’s biggest advantages in AI development. The country’s technology giants collect vast amount of data, and sharing among government agencies and companies is common.

But the Oxford University report says that data alone is not going to be enough for the country to win any AI arms race. A lack of experienced AI researchers, innovation in algorithms and hardware disadvantages are key factors expected to hold China back.

“Due to their high initial costs and long creation cycle, processor and chip development may be the most difficult component of China’s AI plan,” the report found.

“Due to their high initial costs and long creation cycle, processor and chip development may be the most difficult component of China’s AI plan,” the report found.

Lee Kai-fu, Google’s former China head who now manages about US$2 billion in investments as chairman and chief executive of the technology-focused venture capital firm Sinovation Ventures, acknowledges that China is playing catch-up to the US but thinks the balance is tilting due to the country’s practical application of AI and huge pools of data.

“I believe that China will soon match or even overtake the US in developing and deploying AI,” he writes in his new book, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley and the New World Order , arguing that China’s entrepreneurs are using AI to solve real-world problems just like entrepreneurs in the 19th century applied the invention of electricity to practical concerns such as cooking, lighting and the powering of industrial equipment.

According to Lee, this transition towards implementation helps China avoid its weak point in “outside the box” approaches to research and a lack of top-tier researchers, and leverage its most significant strength – “scrappy entrepreneurs with sharp instincts” for building robust businesses.

“China is very close to a techno-utilitarian approach,” Lee said at a book preview event in Beijing in August. “The government is willing to let technology launch, to see how it goes, and then rein it back if needed.”

Last month Jack Ma, co-founder and executive chairman of e-commerce giant Alibaba, set out his vision for “new manufacturing” in China, saying that industry must embrace AI and big data or risk getting left behind. As more data is generated, customisation will be key – instead of creating 2,000 pieces of clothing that are exactly the same in five minutes, the challenge will be to create 2,000 different pieces within the same time.

And Terry Gou Tai-ming, founder and chairman of Taiwan's Hon Hai Precision Industry, the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer known, said this year that the company, which is known by its trade name Foxconn Technology Group, intends to become an AI platform rather than just a manufacturing enterprise, with plans to invest at least US$342 million over five years to recruit talent and deploy AI applications in all its production sites.

Retail has been an early AI test bed on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. Checkout-free grocery stores are made possible by computer vision technology – the branch of AI that enables machines to “see” objects and identify the goods people are buying. E-commerce giants Amazon.com and Alibaba both introduced unstaffed stores last year.

But China appears to have achieved particular success in the field of facial recognition technology, with SenseTime becoming the world’s most valuable AI technology start-up.

Apart from contributing to China’s efforts to build the world’s biggest facial recognition-enabled surveillance network, SenseTime has deployed its AI technology and applications in smart cities, smartphones, internet entertainment, automobiles, finance, retail, and other industries.

Venture capitalists like Lee are behind an increasing number of funds bankrolling the country’s AI start-ups. China’s AI industry has attracted the most financing, accounting for 60 per cent of all global AI investment from 2013 to the first quarter of 2018, according to a July report by Tsinghua University.

Zhang Mo, a former engineer at Microsoft, IBM and Huawei Technologies, is one of many entrepreneurs returning to China to tackle AI. After completing a master’s degree in innovation in Singapore, she decided to start an AI venture in China and named it Moshanghua, after a Chinese poem that alludes to the return of loved ones – “flowers are in bloom on your way back”.

“China has an immense and fast-growing AI market,” she said at her office, which sits in the centre of Zhongguancun, a technology hub in Haidian District, Beijing. “An increasing number of overseas graduates are now coming back, and are clustering in companies to work alongside their smarter peers [in AI].”

The Tsinghua report said China has about 8.9 per cent of the world’s total AI talent pool, compared with 13.9 per cent for the US, but it also finds that the country only has one fifth of the very ‘top-tier talent’ the US has. And the jury is out over academic research, with some observers noting a growth spurt in China while others still say the US has the lead in high quality papers and innovation.

An Hui, director of Information Industry Research Institute at CCID Wise, a think tank under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) in China, and chief secretary of the China-based non-for-profit Artificial Intelligence Innovation Alliance, cautions against blind optimism and hype.

“Despite development, the gap between China and the US is still a far cry in terms of in-depth applications, such as identification of micro-expressions under computer vision or hardware-related ones, so we’d better keep our cool,” An said.

China also has to watch against repetitive efforts to develop the same AI applications, according to An. “Because it’s a vast market, players tend to develop on their own and take up a certain chunk of market share,” he said. “Innovation needs overall guidance, instead of letting it run its own course.”

National rivalries in AI must be put aside, An said, echoing Liu He’s remarks in Shanghai last month and the views of senior executives from US technology giant Google who also attended WAIC.

For example, Lily Peng, product manager of Google AI’s medical imaging team, said she hopes companies from the US and China can work together to develop algorithms that can be applied to both populations, taking account of genetic differences and other diverse factors.

“AI is borderless, whether it’s research, investment or industry collaboration,” said An. “Mentioning the US in our [China’s] AI development plans does not mean it’s a direct rival – instead, we must learn from the US, from each other.”

No comments:

Post a Comment