Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd —in his keynote address at the

New China Challenge conference in October—considered the strategic competition

between the United States and China. This article is adapted from his speech.

As Prime Minister of Australia, through the Australian Defence White Paper of 2009, I was proud to commission the largest peacetime expansion of the Australian Navy in its history—growing our surface fleet by a third and doubling the submarine fleet. That naval expansion had a strategic purpose in mind—namely, the change in the economic and military balance of power between China and the United States. The white paper concluded:

Barring major setbacks, China by 2030 will become a major driver of economic activity both in the region and globally, and will have strategic influence beyond East Asia.

The crucial relationship in the region, but also globally, will be that between the United States and China. The management of the relationship between Washington and Beijing will be of paramount importance for strategic stability in the Asia-Pacific region. . . .

China will also be the strongest Asian military power, by a considerable margin. Its military modernization will be increasingly characterized by the development of power projection capabilities. . . . But the pace, scope and structure of China’s military modernization have the potential to give its neighbors cause for concern if not carefully explained, and if China does not reach out to others to build confidence regarding its military plans. . . .

If it does not, there is likely to be a question in the minds of regional states about the long-term strategic purpose of its force development plans, particularly as its military modernization appears potentially to be beyond the scope of what would be required for a conflict over Taiwan. 1

This was several years before there was any evidence of Chinese land reclamation in the South China Sea.

Dealing with the complexities of the changing East Asian security environment over the years has had its own challenges for U.S. allies, most of them invisible to the Washington policy establishment. In the midst of all this, Australia sought to prosecute a balanced relationship with Beijing: deeply mindful of our differences in security interests and underlying values, while pursuing an economic relationship to our mutual advantage. At various times my government incurred Beijing’s wrath on human rights—on Tibet, Xinjiang, and Australian-Chinese citizens, for instance; on trade—such as when we refused to allow Huawei access to the Australian telecom and broadband network; or in rejecting certain strategic foreign investment proposals—as when the state-owned Chinalco sought to take over the Australian mining giant Rio Tinto.

Meanwhile, we expanded our security dialog with Beijing, our trade volumes doubled, and we approved the vast bulk of Chinese foreign investment in non-sensitive areas of the economy. Australia also ended up with more Chinese students in its universities than in any other country in the world after the United States, and we worked intimately with Beijing through the G20 during the global financial crisis to help stabilize financial markets and return growth to the global economy.

All this is to underline that there is nothing quite like dealing with the Chinese state firsthand to focus the mind on what is strategically important—and what is mere political ephemera.

How does Xi’s China See Its Future?

I believe history will mark 2018 as a profound turning point in relations between the two great powers of the 21st century—the United States and China—even if none of us can confidently predict what the long-term geopolitical trajectory will be.

China’s rise as a global power did not begin in 2018 but rather 40 years ago. This rise has continued under multiple Chinese administrations, albeit within single party rule and a continuing strategic culture, focused on China’s acquisition of national wealth and power. But while what China internally refers to as “comprehensive national power” has increased steadily under Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao, what has changed under current President Xi Jinping has been the clarity of articulation of China’s strategic intentions. This is reflected also in the increased operational tempo of China’s military, diplomatic, and economic policy behaviors around the world. If the pillars of strategic analysis are capabilities, intentions, and actions, it is clear from all three that China is no longer a status-quo power.

It is important, however, to be clear about where increased national wealth and power fit within Xi’s wider worldview and his own particular set of national priorities. A road map of strategic goals does not necessarily say which China is likely to achieve. China’s leaders face a complex brew of domestic and international challenges that would cause most to go grey prematurely. But China may well prevail.

Xi has consolidated internal power by purging those who opposed his appointment, ruthlessly using the anticorruption campaign to that end (as well as to clean up the party). He has imposed multiple changes to the command structures of the military, security, and intelligence apparatus; nonetheless, there is grumbling about the cult of personality, the abolition of presidential term limits, and strategic overreach vis-a-vis the United States. Still, it is impossible to readily identify a potential replacement, or even a successor. Policy planners in the West and Asia therefore would be prudent to assume Xi will be with us at least another decade, health permitting.

The crackdown in the far-west province of Xinjiang is beginning to generate a new human rights agenda against Beijing—not only from the West, but from parts of the Muslim world as well. Taiwan represents an even greater problem given the resilience of its democracy and its growing sense of local national identity separate from the mainland, reinforced by total generational change for whom pre-1949 realities mean little. Tibet also remains problematic. All these issues challenge national unity.

Real economic growth has been slowing since early this year as a product of a slowdown in market-based economic reforms, and a “from-the-top” deleveraging campaign to reduce the indebtedness of second-tier banks and financial institutions, as well as the impact on business confidence of the trade war with the United States. This has resulted in rapid fiscal- and monetary-policy easing by the central bank, which has slowed actions to deal with China’s massive debt (estimated at 260 percent of GDP). 2 The Chinese public has begun to demand that the party act rapidly and radically on air pollution and climate change. In short, the economy could well turn into a liability, rather than the strength it has been in enhancing party legitimacy for the last 40 years.

China’s relationships with neighboring states nonetheless are in a reasonable state from Beijing’s perspective. The relationship with Russia is being strengthened by growing strategic interests against the United States. Beijing also is taking the temperature down in its normally problematic dealings with both Tokyo and Delhi. Japan and India have been happy to oblige, and at least for the foreseeable future will continue to be, not only for their own domestic reasons but also because they are uncertain where the United States is headed in the long term. Vietnam, the Philippines, and Burma are less problematic than before, in part because there now is less solidarity among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the South China Sea. The limited rapprochement between the United States and North Korea, and the much deeper one between the two Koreas, have removed long-standing impediments to structural improvement of China-North Korea relations that had been cold since 2011.

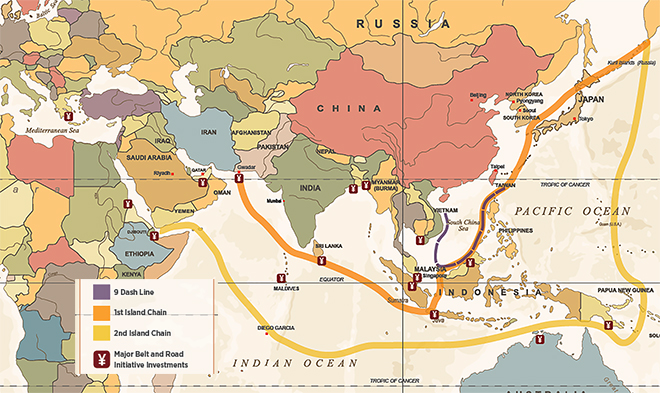

On its maritime periphery, China faces newly assertive U.S. behavior in challenging maritime territorial claims in the South China Sea. But across wider southeast Asia, the regime sees a region gradually drifting in direction. Not long ago, Cambodia was seen as China’s only reliable partner in ASEAN; that is no longer the case. ASEAN is in strategic-hedge mode, in part because of the enormity of the Chinese economic footprint over the region relative to the United States, Europe, or even intra-ASEAN trade and reinforced by the investment dynamics of China’s Maritime Silk Road. The election of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia, however, represents a fresh problem, and major Chinese infrastructure construction contracts with the Malaysian government have been suspended. But based on China’s experience elsewhere, this is likely to be seen as a tactical rather than strategic setback. The central factor working in China’s favor is the absence of U.S. or European alternatives to Chinese markets, foreign direct investment, and capital flows.

China’s continental periphery has not been plain sailing. Nonetheless, for every country that pushes back against China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), another queues up. Where resistance is encountered—on debt, labor and environmental standards, or loss of local sovereignty—many in Washington seem to think it the end of the matter. China, however, usually changes tactics to deal with the particular problem it has encountered and works it through to a new pragmatic outcome, as seen in countries as diverse as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Zambia. With more than 70 countries signed up to the BRI, China’s biggest impediment in delivering fully on its vision is less likely to be foreign resistance than the long-term drain on the financial resources of the Chinese state from investments in too many financially non-performing projects.

On the future of the global rules-based order, China should be reasonably content with its efforts to shape the system in its image. The U.S. withdrawal from the U.N. Human Rights Commission is a godsend for Beijing, which has long found this to be the single-most problematic multilateral institution because of its capacity to attack the domestic legitimacy of the Chinese state. Similarly, the U.S. attack on the World Trade Organization has enhanced China’s standing there despite China’s general reluctance to embrace fundamental global trade liberalization or fully open its own markets.

U.S. criticism of the U.N. itself similarly has enabled China to look like a responsible global stakeholder in the multilateral system, enhanced by China’s increasing aid budgets and greater contribution to U.N. peacekeeping, as well as an increasing of appointments of Chinese personnel across U.N. agencies. China’s main problem in the U.N. Security Council is its close voting relationship with Russia on resolutions that are sensitive to non-Western states, as on Syria, where China’s behavior has alienated the European Union and the Gulf states.

Nonetheless, China’s global economic diplomacy across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania through its formidable and growing global diplomatic network means China is able to marshal formidable political support in multiple U.N. fora. Whether such support for the country’s tactical interests will translate ultimately into more fundamental structural support for a formal rewrite of the rules and practices of the current international system is very much an open question. China’s historical diplomacy usually has been more gradualist than that—to bring about de facto changes over time, rather than necessarily proclaim de jure “reform.”

Therefore, from Beijing’s perspective, the country, the region, and the world represent a complex picture. What is clear, however, is that China under Xi Jinping has a worldview and a grand strategy to give it effect. And it would be prudent to assume, absent major and enduring policy change in Beijing or Washington, that China has at least some chance of success. Xi and his comrades are determined to defeat the liberal-capitalist order with a different political, economic, and perhaps international model aided by the new technologies of political and social control, grafting these onto the traditions, culture, and ideology of a 100-year-old Communist Party and combining them with a so-far successful authoritarian-capitalist model.

Xi Jinping and author Kevin Rudd greet each other in Canberra, Australia, in 2010. At the time, Xi was China’s vice president and Rudd was serving as Australia’s prime minister. (Associated Press/Mark Graham)

Xi Jinping and author Kevin Rudd greet each other in Canberra, Australia, in 2010. At the time, Xi was China’s vice president and Rudd was serving as Australia’s prime minister. (Associated Press/Mark Graham)

Strategic Engagement Vs. Strategic

Competition

If China’s operational strategy toward the United States has been largely constant over the past 40 years, albeit with a new clarity and operational intensity under Xi, the U.S. response to this Chinese strategy has changed fundamentally. This was articulated clearly in the 2017 National Security Strategy and is stated plainly in the U.S. National Defense Strategy of 2018. It is shown by the trade war launched in June 2018 and intensified during the summer. And we have seen it most clearly in the October 2018 speech by U.S. Vice President Mike Pence at the Hudson Institute.

Taken together, these various statements of changing U.S. declaratory intent lead to the conclusion that the period of “strategic engagement” between China and the United States in the post-1978 period has ended.

Engagement did not produce sufficiently open Chinese markets for U.S. firms for export and investment. China, rather than becoming a “responsible stakeholder” in the global rules-based order, instead is constructing an alternative order with “Chinese characteristics”; and rather than becoming more democratic in its domestic politics, China has decided to double down as a Leninist state.

In addition, China intends to push the United States out of East Asia and the Western Pacific, and in time to surpass the United States as the dominant global economic power.

China seeks to achieve its national and international dominance through the hollowing out of U.S. domestic manufacturing and technology by means of state-directed industry; through a range of economic incentives and financial inducements to U.S. partners, friends, and allies around the world; and through the rapid expansion of China’s military and naval presence from the East China Sea, the South China Sea, across the littoral states of the Indian Ocean and Djibouti in the Red Sea.

These factors, along with Russia, combine to form the central strategic challenge to U.S. security and prosperity for the future, warranting an urgent change in course away from strategic engagement with China to a new period formally characterized as “strategic competition.”

This new U.S. analysis of China’s national capabilities, intentions, and actions will be translated into a new multidimensional operational strategy aimed at rolling back Chinese diplomatic, military, economic, and ideological advances abroad.

If this new direction in U.S. declaratory strategy toward China is reflected in future U.S. operational policy, 2018 will indeed represent a fundamental disjuncture in the U.S.-China relationship.

The Future of U.S. Strategy

There are a number of questions the U.S. administration should consider as it operationalizes its new competition with Beijing. I will leave discussion of the wisdom of this strategy to the U.S. public, but U.S. friends and allies around the world will be considering these factors as well.

First, what is the desired end-point of U.S. strategy? What does Washington do if China does not acquiesce to the demands outlined in the Vice President’s speech, but instead explicitly rejects them? What happens if the strategy not only fails to produce the desired objective, but instead produces the reverse, namely, an increasingly mercantilist, nationalist, and combative China?

Second, if we are now in a period of strategic competition, what are the new “rules of the game?” How is a common understanding to be reached with Beijing as to what these new rules might be? Or are there now to be no rules, except those that will be fashioned over time by the dynamics of this new competitive process? During 40 years of bilateral strategic engagement, culture, habits, norms, and—in some cases—rules evolved to govern the bilateral relationship and became second nature to several generations of political, diplomatic, military, and business practitioners. What will replace them now, to govern the avoidance of incidents at sea (such as recently occurred between a Chinese warship and the USS Decatur[DDG-73]); incidents in the air; cyberattacks; nuclear proliferation; strategic competition in third countries; the purchase and sale of U.S. Treasury Notes; or the future of the exchange rate and other major policy domains?

Third, is any common strategic narrative between China and the United States now possible, to set the conceptual parameters for the future of the bilateral relationship? Strategic engagement implied a set of mutual obligations that the United States now argues China has fundamentally breached. But having already skipped through a short-lived concept of strategic coexistence and in the absence of new rules to govern the relationship, how can the two countries arrest any rapid slide between strategic competition and containment, confrontation, conflict—and even war?

If history is any guide, these changes can unfold more rapidly than many postmodern politicians might expect. The escalation from a single incident in Sarajevo in summer 1914 is a sobering point, even if the age of nuclear weapons has deeply changed the traditional strategic calculus since then.

Fourth, if some U.S. strategic planners are indeed considering the possible evolution of strategic competition with China into full-blooded containment, comprehensive economic decoupling, or even a second Cold War, then they would do well to examine closely the underlying logic of U.S. diplomat George Kennan’s famous 1946 “Long Telegram” and his subsequent “X” article on “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” published in Foreign Affairs the following year. Kennan argued that if properly “contained,” the Soviet Union ultimately would break up under the weight of internal pressures. It would be a heroic assumption, however, to expect that the Chinese system would do so should a similar policy be applied. It might. But it probably will not, given the resilience of the Chinese domestic economy, its capacity to secure its energy needs from other U.S. adversaries, and the fresh potentialities offered by the various new technologies of political and social control now available to Beijing. On this point, it is worth noting that on 28 September 2018 the People’s Republic of China surpassed the Soviet Union as the longest-lasting communist state in history.

Fifth, is the United States convinced that the emerging Chinese model of authoritarian capitalism represents a potent ideological challenge to democratic capitalism, whether it be of the conservative, liberal, or social democratic variant? The Soviet Union constructed client regimes around the world of a similar ideological nature to its own. Is there evidence that China is doing the same? Or is China interested in a more limited version of supportive state relations, without any appeal to ideology, without armed intervention, relying instead on extensive, continuing, and significant infrastructure investment and direct financial aid?

Sixth, will the United States be prepared to provide the world a strategic counteroffer to the financial commitment reflected in China’s multitrillion-dollar programs of the BRI, concessional loans, and bilateral aid flows? Or will the United States continue to slash its own aid budgets and reduce the size of its foreign service? Recent U.S. support for a new capital injection into the World Bank is a welcome development. But it pales into insignificance compared with the dimensions of the BRI. In time, the World Bank’s global balance sheet may be eclipsed by the lending capacity of the China-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Seventh, how will the United States compete over time with the magnitude of China’s trade and investment in Asia and Europe? How will the cancellation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership with Asia and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with Europe affect the relative significance of the United States and China as trade and investment partners? China already is a bigger economic partner with most of these countries than the United States—how will the United States resist the effect of the centripetal force of the Chinese economy in drawing these regions increasingly into China’s orbit?

Eighth, how confident is the United States that its friends and allies around the world will fully embrace its new strategy of strategic competition with China? After President Donald Trump’s imposition of import tariffs on Japan and India or his sustained public attacks on major U.S. allies Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada—and NATO in general—is the United States confident these countries will embrace this new strategy against China? Or will these countries continue to hedge their bets in their relations with Washington and Beijing? Will they wait until it becomes clearer whether this shift in U.S. policy toward China is permanent, whether it will be translated into real policy—and whether it will succeed? And what about countries in southeast Asia, or the Middle East, where China is now a bigger buyer of oil and gas than the United States?

Ninth, what constitutes the appeal to the rest of the world to support this new U.S. strategy as an alternative to a China-dominated region and world? Vice President Pence’s address was consciously and eloquently couched in terms of U.S. interests and values. But it made no appeal to the international community’s common interests and values, historically shared with the United States and articulated through the U.S.-led global rules-based order crafted after the last world war. Instead, the world has seen the current administration walk away from a number of critical elements of the order constructed by its predecessors over seven decades (human rights, multilateral trade regimes, climate change, the International Criminal Court, and U.N. aid agencies) under the rubric of the nationalist call of “America First.”

Last is the immediate question of the potential impact on the global economy and climate change action of a major cleavage in U.S.–China relations. If bilateral trade collapses or even reduces significantly as a result of radical decoupling, what will be the impact on U.S. and global growth in 2019 and beyond, and what are the prospects of it triggering a global recession? Similarly, in light of the October 2018 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change pointing to potential planetary disaster because of inadequate action by the world’s major greenhouse-gas emitters, what will happen if the current global climate change regime becomes a major casualty of the implosion in the U.S.–China relationship? Will China revert to its own limited national measures?

U.S. and other policy makers should be considering these ten significant questions as they seek to put flesh on the bones of the administration’s new era of strategic competition with China. The United States should embrace such a new approach with its eyes wide open. In navigating these uncharted waters, no one wants to see the triggering of unintended consequences, least of all accidental conflict; 100 years on, the warnings of 1914 still ring loudly in all our ears.

It is in no way in China’s interest to want either an economic war or physical confrontation with the United States, because China knows it would in all probability lose both. China knows that it is still the weaker power. Nonetheless, history teaches that nationalism can be a potent force often defying classical strategic logic, whether that of China’s “Seven Military Classics” that collectively urge caution, or Carl Von Clausewitz, or even Alfred Thayer Mahan.

The reasons for the relationship’s changing nature are largely structural: China has now assumed such a global and regional critical mass in its economic and military capacity that a revision of the U.S.–China relationship has become essentially inevitable. That comes even before considering the radically different ideological traditions and future aspirations of what are now the two largest economies—and militaries—in the world. China’s global and regional policy has changed significantly over the past decade. Whether in the South China Sea, South East Asia, Eurasia, Africa, Latin America, or the current structure of the international order, China indeed has been the dynamic factor, whereas until recently the United States has been the constant.

The Avoidable War?

Most who take the U.S.–China relationship seriously struggle with the intellectual and policy complexity of the subject before us. It is not easy; it is hard, in fact. And the charged political atmosphere in which we find ourselves is a difficult environment in which to work. The proponents of one view are variously described, usually under the breath, as China appeasers (or less politely as “panda huggers”). Those of a different view are described as warmongers. We need to be wary of the reconstitution of any modern “Committee on the Present Danger,” where those seeking to explain the complexity of China’s rise are pronounced guilty of un-American (or in my case, un-Australian) activities if we offer a complex response to what is rendered as the simple question, “What to do about China’s rise?” The bottom line is that space is now contracting, both in the United States and Australia, for open, considered public debate and discussion on this question.

It is easy in politics simply to join the cheer squad. It is much harder to think through what might constitute sound, enduring public policy and be capable of realizing agreed objectives to preserve freedom, prosperity, and sustainability in the long term, while not producing unintended consequences along the way—least of all, crisis, conflict, or war.

Both China and the United States are old enough, experienced enough, and indeed battle-scarred enough to ultimately sort this out. When I helped establish the Asia Society Policy Institute, and former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger became inaugural chair of its International Advisory Board, we asked him what our mission should be.

In a classically Kissingerian haiku, Henry responded that we should seek to identify three things about the world today: First, what is really happening? Second, why is it happening? Third, and most important, what are we not seeing?

We in the policy community and the academy have a particular responsibility, at this critical stage of the process, to shed as much light as possible on what we are seeing, rather than simply applying additional heat. And shining light also requires us to understand reality as perceived through the eyes of others, even if we choose then to reject it.

I am on the side of the avoidable war. We must find a third way, beyond the extremes of either capitulation or confrontation, to help navigate our way through the Thucydidean dilemma that we now confront. At times like these, jingoism is easy, whether in Beijing or Washington. By contrast, solid strategy and good policy are hard. I look forward to the contributions of those of good heart and strong mind seeking to find a way through this most classical of modern security dilemmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment