By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

UPDATED with contract details WASHINGTON: A deceptively modest award for a blandly named “Unified Platform” actually gives contractor Northrop Grumman the lead role in developing the next generation of weapons for Cyber Command. Other companies may offer specific software and hardware modules, but as “Systems Coordinator,” Northrop now gets to design the virtual chassis all those upgrades must fit on.

The goal is to give the 6,200-strong Cyber Mission Force — created in a hurry and equipped with a hodgepodge of kit developed by different armed services and intelligence agencies — a common, compatible set of tools so they can act in cyberspace as a coordinated military unit. In particular, Unified Platform will let the newly independent Cyber Command conduct military operations in cyberspacewithout depending on National Security Agency infrastructure, as it has done since its creation, and without interfering with NSA’s intelligence collection.

The need is urgent and the pace intense: Following just eight months after a Request For Information in February and four months after a Request For Proposals in June, Friday’s $54 million award is the first piece of a fast-moving effort for which the Pentagon wants to spend $217 million over five years.

But a skeptical Congress knocked $2.2 millionoff the Unified Platform request in the 2019 appropriations bill, citing a “lack of justification on foundational efforts.” The program’s problem? It exists at the unhallowed intersection of clandestine operations, information technology, and federal contracting, so what it actually doesis shrouded in classification, buzzwords, and jargon.

Yesterday, though, a veteran cyber warrior — a retired Air Force two-star turned principal assistant secretary for cyber policy — made a good effort at explaining it in English:

“It’s a unifying platform in a lot of ways because it brings to bear a lot of data and it helps commanders…make decisions,” Edwin Wilson told reporters. Unified Platform will pull together information from disparate systems into a single, standardized view of the virtual battlefield that shows their commanders not only the threats, but also the status of their own disparate forces — “the readiness and the capabilities that we have both on deck for offensive or for defensive operations,” he said — and command-and-control mechanisms to employ those capabilities.

Navy cyber sailors

Cyber Maneuver

Unified Platform isn’t as sexy as a fighter plane or a nuclear submarine. To the untrained eye, all it will ever look like is a bunch of people staring at screens and typing. But militarily, it’s as essential to cyber war as planes are to war in the air or subs to war under the sea. Like the air, sea, and outer space — but unlike the land — cyberspace is a domain which humans can’t enter without specially designed machines. Indeed, much like the electromagnetic spectrum used for radar and radio, humans can’t even perceive what’s happening in cyberspace without specialized tools.

What makes cyber operations even more challenging, however, is that you can’t even see into a particular network, let alone defend or attack it, unless the specific software you’re using is compatible with the specific software running that network. Offensive cyber tools in particular often have to be exquisitely custom-built to affect a particular target, as Stuxnet was for the Iranian nuclear program.

Russian train tracks are farther apart than those in Europe. As in cyberspace, incompatible network standards complicate both military and civilian operations.

The closest equivalent in the physical world is how railways in the former Soviet Union are standardized on a different gauge than the rest of Europe. Rail cars built for one network can’t travel on the other without physical modifications, a major impediment to German supply lines during World War II. Moving from one network to another in cyberspace often requires a roughly comparable reconfiguration — except that instead of being a strange quirk of one particular border region, it has to happen all the time.

The closest equivalent in the physical world is how railways in the former Soviet Union are standardized on a different gauge than the rest of Europe. Rail cars built for one network can’t travel on the other without physical modifications, a major impediment to German supply lines during World War II. Moving from one network to another in cyberspace often requires a roughly comparable reconfiguration — except that instead of being a strange quirk of one particular border region, it has to happen all the time.

Future wars will require decision superiority in a time of fast-paced conflicts across multiple domains. Raytheon exec Rick Yuse outlines 5 advanced technology enablers to gain critical advantage.

Today, Cyber Command is like a railroad in the bad old days before standardized gauges, running different kinds of trains on different kinds of track. Specifically, today’s Cyber Command consists of four service components — Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps — that are all trained to a common standard but equipped with different sets of hardware and software.

While that heterogeneity was probably a necessary compromise to get the force operational as soon as possible, it makes it harder for multiple teams, especially teams from different service components, to share information and act together as a larger force. But that kind of coordination is what’s required to scale up from combatting ISIS cells and online propaganda to waging cyber warfare against sophisticated adversaries like Russia and China.

Maneuver in cyberspace doesn’t require physical movement the way it does in other domains, but it still requires bringing different units’ capabilities to bear at the right place, time, and target in a coordinated way. If your teams don’t have compatible software, they can’t easily access the same networks, which means they can’t combine their forces. Unified effort requires a Unified Platform.

SOURCE: Air Force 2019 budget submission, Vol. 3A, page 779

Deliverables & Deadlines

The Unified Platform program doesn’t fit tidily into a traditional acquisition framework, but budget documents and anonymous sources outline how it will run. Instead of standard step-by-step phases, the program — with the Air Force acting as executive agent — involves fast-paced, overlapping activities that range, to quote the 2019 budget submission, from “prototype development, risk reduction, testing, and integration of cyber capabilities…. (to) delivering enhanced cyber effects to the Combatant Commanders.”

That last one, “delivering…effects,” specifically means getting working hardware and software to Cyber Mission Force teams so they can conduct real-world operations — even as development work continues to refine that technology based on operators’ feedback. And all this has to happen fast, with the goal being to “deliver capability” to operational users in fiscal 2019.

Again, last week’s $54 million award to Northrop Grumman is just the beginning. To keep up with the pace of both operational needs and technology improvements, the Unified Platform will involve multiple “new and existing contractual vehicles” (quoting the 2019 budget again), rather than a single big contract. The vehicles will include Defense Department-wide IT contracting mechanisms like DISA’s Encore II and even government-wide ones like GSA’s Alliant, as well as contracts specifically written for the program.

UPDATED The government will be its own “primary systems integrator” ultimately responsible for putting together all the pieces into a usable product for the Cyber Mission Force, an Air Force spokesperson told me, with Northrop Grumman assisting it as “systems coordinator.” Other companies may get contracts to develop other aspects of Unified Platform, the spokesperson explained, but Northrop will work with these other developers to “provide the tools, processes, and coordination necessary” to ensure they deliver their pieces of the Unified Platform correctly. UPDATE ENDS

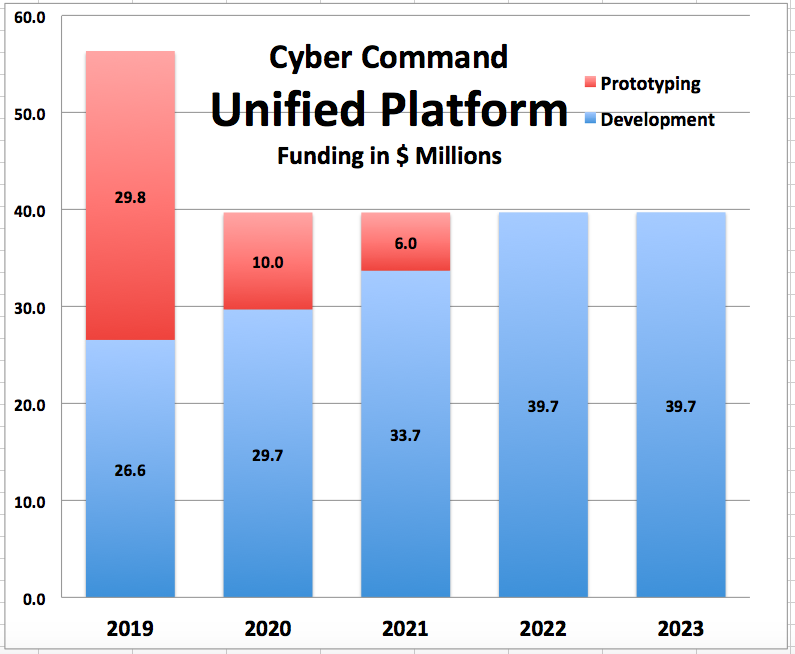

Funding starts with a spike of $56 million in fiscal year 2019 (again, that’s after Congress cut $2.2 million from the request) before leveling off to $33.7 million a year in 2020-2023 (which is as far as detailed projections run). The 2019 money is almost a 50-50 mix of prototyping (Budget Activity 4) and operational development (BA 7), but over time the prototyping funds fall off rapidly as development rises, almost dollar for dollar.

So what’s being prototyped? Two things:

The first and fastest activity — beginning now and finished by April 1, 2019, halfway into the fiscal year — is prototyping what budget documents call a Service Oriented Architecture (SOA). SOA is an IT sector term of art: Instead of each user having a complete package of software on his or her device, they connect over a network to a central server offering an array of different applications, all written to a common standard to allow easy upgrades by swapping in new software and hardware as desired. (This “loose coupling” is similar to the broader engineering concept of modular open architecture, which uses common standards to plug-and-play all sorts of components, physical machinery as well as software).

The second prototyping effort, which also begins immediately but lasts until October 1, 2021 (the end of the fiscal year), is “Minimum Viable Product build-up.” MVP is a particularly confusing and contentious bit of IT jargon, but the best definition I’ve seen is that, in essence, “minimum viable” means it’s the earliest version of the software that users can interact with and give useful feedback on.

This approach a crucial part of so-called Agile development, something Northrop Grumman prides itself on doing. Agile has become a widely derided buzzword but, when actually implemented properly, it involves getting user feedback as early and often as possible, allowing developers to make constant small improvements, and quickly delivering an adequate product that can be continually upgraded, rather than trying to fulfill a long list of formal requirements in one big bang.

This prototyping work overlaps with the development phase. Indeed, the Agile process doesn’t draw a bright line between the two in the same way traditional Pentagon practice does, and the $54 million award to Northrop seems to cover a mix of both.

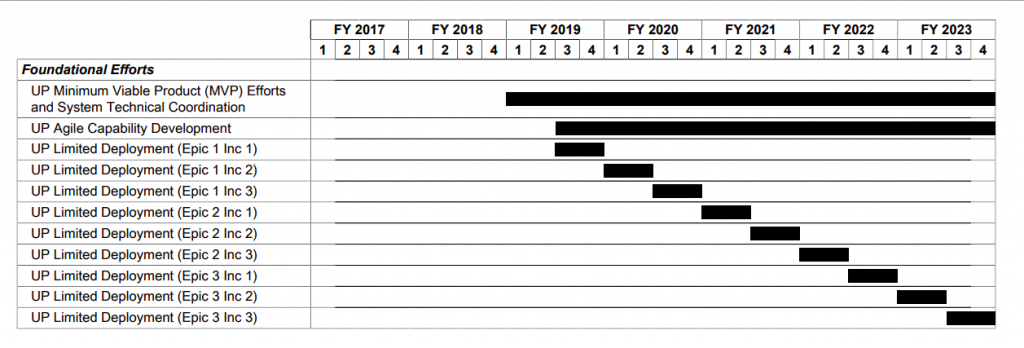

The Minimum Viable Product work that begins this month continues (after the initial prototyping “build-up”) through 2023, the five-year defense program.

Agile Capability Development officially starts mid-2019 (the third quarter of the fiscal year) and runs through fall 2023 (the end of the FY).

The initial Limited Deployment of the first operational version of the Unified Platform — known in Agile jargon as an “epic” — occurs in the second half of fiscal 2019.

Limited Deployments of further upgrades will follow through the end of 2023, with an incremental upgrade every six months and a major upgrade (called an “epic” in Agile jargon) every 18 months.

But the budget documents also call for upgrades to achieve “near-immediate integration into the UP baseline for delivery to cyber warfighters”: In other words, if cyber teams need something now, they shouldn’t have to wait for the six-month upgrade cycle.

This is an extremely ambitious agenda, one that pushes the limits of acquisition bureaucracies designed for industrial age mass production. Whether the Pentagon can pull it off is an open question. But if they can’t, the US will fight in cyberspace at a serious disadvantage.

No comments:

Post a Comment