by Mark J. Valencia

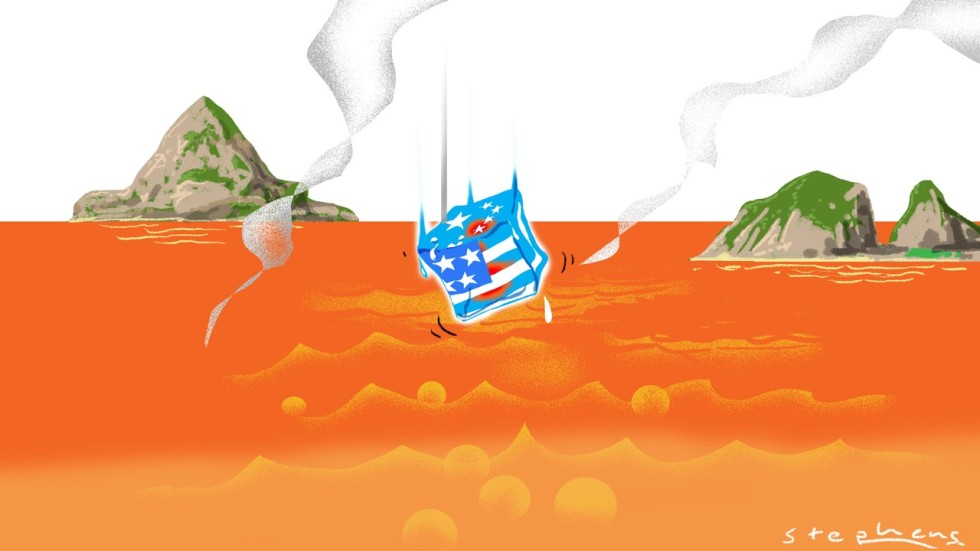

The long-anticipated top-level diplomatic and security dialogue between the United States and China has come and gone with no apparent progress on any of the issues bedevilling bilateral relations, especially the simmering tensions over the South China Sea. Glaringly, the two sides have not announced any agreement on risk-reduction measures, and sharp policy differences remain.

The long-anticipated top-level diplomatic and security dialogue between the United States and China has come and gone with no apparent progress on any of the issues bedevilling bilateral relations, especially the simmering tensions over the South China Sea. Glaringly, the two sides have not announced any agreement on risk-reduction measures, and sharp policy differences remain.

The second annual US-China Diplomatic and Security Dialogue was held on Friday in Washington, between delegations led by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Defence James Mattis for the US and Politburo member Yang Jiechi and Defence Minister Wei Fenghe for China.

The meeting had originally been planned for September in Beijing, but had to be cancelled after China declined to make Wei available to Mattis. Given the rising tension between the two militaries, it is surprising that the dialogue even took place at all, and that China agreed to send its representatives to Washington for the rescheduled meeting. It would seem that either there were urgent security matters to discuss, or China wanted something – or both.

Watch: Video shows near collision between US and Chinese warships

Perhaps the main purpose of China’s dialogue with the US was to prepare for an expected meeting between their leaders on the sidelines of the coming G20 summit in Argentina. Or perhaps Beijing wanted to ascertain if Mattis would stay in his post (there have been rumours that he is leaving Pentagon) and if not, which policymaker would be likely to replace him. China might also have been keen to determine if military relations between the two countries could continue to be productive.

Despite soothing rhetoric, there is clearly concern on both sides. Military-to-military relations are perhaps the most significant dimension of US-China relations because they can be a stabilising force when relations in other spheres break down. In June, President Xi Jinping called the US-China military relationship the “model component of our overall bilateral relations”. Mirroring Xi, the Chinese Defence Ministry has said it hopes the military relationship can become a “stabiliser” for overall ties.

According to General Joseph Dunford, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, the two militaries held a “tabletop exercise” about four months ago to increase transparency and reduce risk of miscalculation. After Mattis and Wei met on the sidelines of an Asian security conference in Singapore in October, Randall Schriver, a top Pentagon official for Asia, said such high-level talks were especially valuable during times of tension.

However, US Vice-President Michael Pence’s cold war rhetoric certainly did not help. In his “us versus them” speech on October 4, he highlighted the “reckless” challenge a Chinese destroyer made to the USS Decatur in the South China Sea and added belligerently: “We will not be intimidated; we will not stand down.” More ominously for China, the US has sent nuclear-capable B-52 bombers over the East and South China seas.

Watch: The South China Sea dispute explained

Given the current state of US-China relations, the security dialogue was considered critical to setting the tone for the near future. Observers had hoped the talks would lead to tension-defusing agreements or at least public statements to that effect. Yet, the joint press conference after the dialogue was far from reassuring.

Both sides characterised the talks as “candid”, which is diplomatic speak for sharp disagreements. The Chinese and the Americans basically reiterated their positions and talked past each other. Yang said Beijing had the right to build “necessary defence facilities” on its own territory. Pompeo said: “We have continued concerns about China’s activities and militarisation in the South China Sea. We pressed China to live up to its past commitments in this area.”

This is a reference to Xi’s supposed pledge to not militarise the Spratly Islands, but this may be a misunderstanding in danger of becoming an alternative fact. Xi never said China would not militarise the islands. According to the translation of his remarks during a state visit to the US in 2015, he said “China does not intend to pursue militarisation” in the Spratly Islands. The key words are “intend” and “militarisation”. Perhaps China might not have intended to militarise the islands. But when Vietnam and the US took what China considered threatening military action in the area, it might have felt a need to respond.

Watch: US presses China to halt militarisation of the South China Sea

Indeed, China has repeatedly warned it is prepared to defend itself if the US persists with provocative intelligence-gathering and freedom-of-navigation operations near its coast and islands. Apparently, China does not consider its defensive installations “militarisation”.

At the press conference, Mattis said the two sides also discussed the importance for all military and civilian vessels and aircraft “to operate in a safe and professional manner, in accordance with international law” – probably a reference to the USS Decatur incident, for which the US considers China at fault. Mattis and Wei also held talks and could have discussed specific risk-reduction measures. But there has been no public information on what was discussed or agreed on, if at all.

Of course, the two sides tried to put their best face on the lack of progress, saying they were committed to peace and stability in the South China Sea, the peaceful resolution of disputes, and freedom of navigation, overflight and other lawful uses of the sea. Both sides spoke of ensuring air and maritime safety, and managing risks in a constructive manner. But these were just platitudes. If lowering tensions and the risks of a clash was the purpose, the meeting would appear to have been a failure.

No comments:

Post a Comment