Fergus Ryan

This report by ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre collates and adds to the current open-source research into China’s growing network of extrajudicial ‘re-education’ camps in Xinjiang province.

The report contributes new research, while also bringing together much of the existing research into a single database. This work has included cross-referencing multiple points of evidence to corroborate claims that the listed facilities are punitive in nature and more akin to prison camps than what the Chinese authorities call 'transformation through education centres’.

By matching various pieces of documentary evidence with satellite imagery of the precise locations of various camps, this report helps consolidate, confirm and add to evidence already compiled by other researchers.

Key takeaways

This ASPI ICPC report covers 28 locations, a small sample of the total network of re-education camps in Xinjiang. Estimates of the total number vary, but recent media reports have identified roughly 180 facilities and some estimates range as high as 1,200 across the region.

Since early 2016 there has been a 465% growth in the size of the 28 camps identified in this report. 12

As of late September 2018—across the 28 camps analysed—this report has measured a total of 2,700,000 m2 of floor space, which is the equivalent of 43 Melbourne Cricket Ground stadiums.

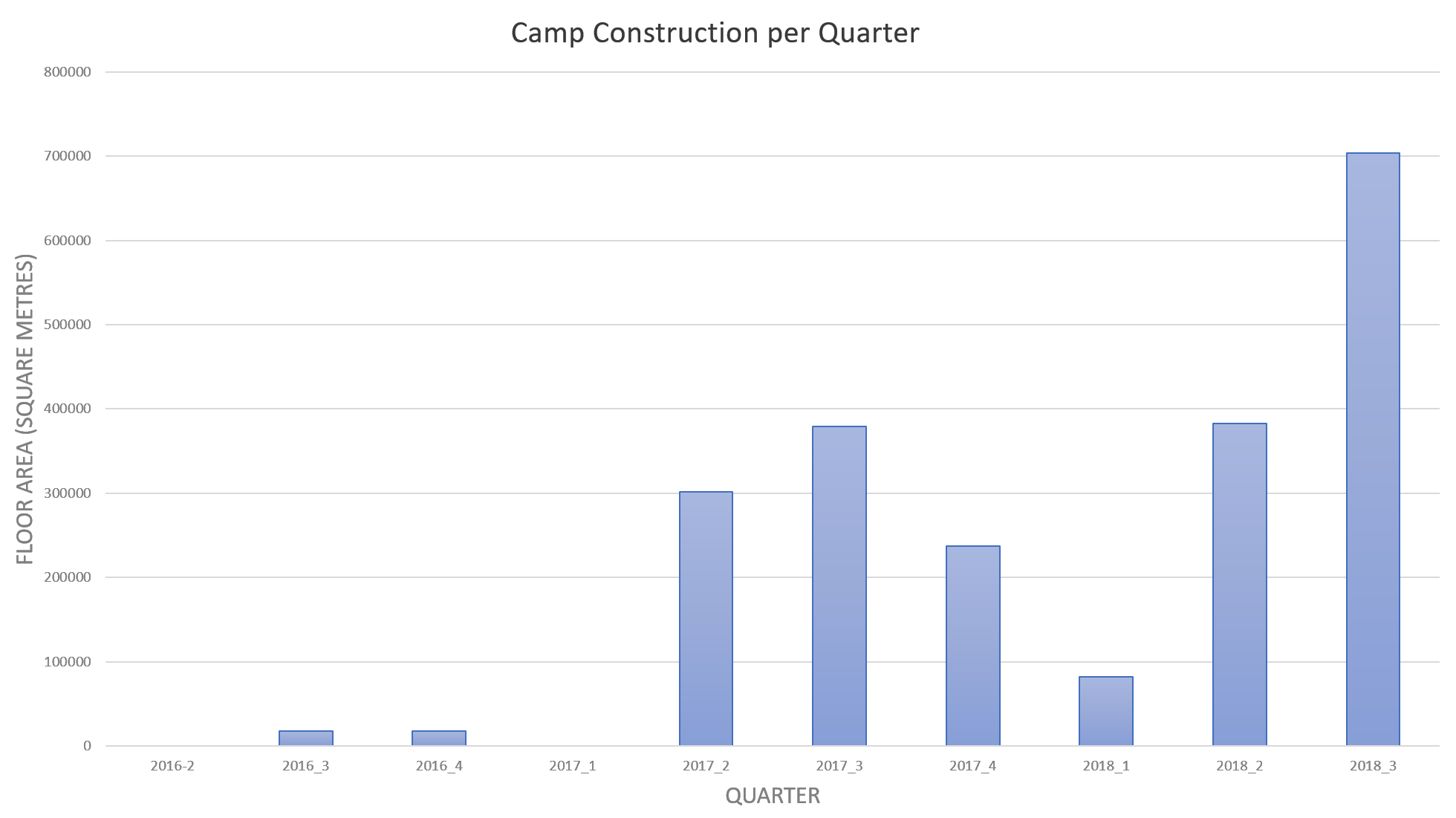

The greatest growth over this period occurred across the most recent quarter analysed (July, August and September 2018), which saw 700,000 m2 of floor space being added across the 28 camps.

Some individual facilities have experienced exponential growth in size since they were repurposed and/or constructed. For example, a facility in Hotan that the New York Times reported on in September 20183 expanded from 7,000 m2 in early 2016 to 172,850 m2 by September 2018—a 2469.29% increase over an approximately 18-month period.

The growth in construction has increased at a considerably faster pace in the summer months, with a spike in construction during the third quarters of both 2017 and 2018.

Introduction

China’s censors have been expunging evidence of the country’s vast network of extrajudicial 're-education’ camps in Xinjiang province from the internet just as fast as researchers have been finding it.

From first-hand testimony to satellite imagery, researchers have now provided empirical data that authoritatively paints a picture of the extent of China’s biggest human rights abuse since the 1989 post-Tiananmen purge.

Word of this rapidly growing network of ‘re-education’ camps first started to spread with interviews of the relatives of detainees.4 Further research drew on information in public construction and service tenders which documented and detailed the sizes and security features of these re-education camps.5

Other documents such as public recruitment notices, government budget reports, government work reports and Chinese articles in local media and social media have helped to reveal details of how Chinese authorities are rapidly expanding this network of camps.

The cumulative effect of this onslaught of evidence, as well as condemnation from US lawmakers6 and the UN,7 has forced Chinese authorities to move from outright denial of the camps’ existence to a public relations offensive in which they present the camps as places for 'free vocational training'8 rather than anything punitive.

This ASPI ICPC report contributes new research, while also bringing together much of the existing research into a single database. This work has included cross-referencing multiple points of evidence to corroborate claims that the listed facilities are punitive in nature and more akin to prison camps than what the CCP calls 'transformation through education centres’.

The report matches the plethora of documentary evidence already uncovered with satellite imagery of this sprawling network of camps. The report takes a conservative approach in deciding what the likely use of each facility is. Each potential camp is assigned a red, orange or green tag representing our level of confidence based on the available open-source data.

The data

This report collects and collates a huge amount of data and it attempted to include as much of that as possible into a database. Some subsets of the database are new—for example, our data on the growth in the size of these 28 facilities. Others have been identified by other researchers, NGOs or media outlets. Where possible, data from these sources has been included in the database, with citations and hyperlinks to the original work.

Brief summaries of the collected data are presented and tabulated in this report; however, using the accompanying database, it is possible to explore all data points in more depth and draw individual conclusions.

The database is by no means an exhaustive list and it will continue to develop and grow as additional datasets are added.9 It is hoped it will provide media outlets, researchers and governments with current and useful information, and become a resource to which they can potentially contribute.

Camps that have multiple points of strong evidence are deemed to be internment camps and were marked green using the traffic light system. These points of evidence include, for example, facilities that are described as ‘transformation through education’ facilities in official documents, that this research has geo-located from tender documents, or that contain physical features captured in satellite imagery such as barbed wire, reinforced walls and watchtowers.

Orange tags on other camps denote a comparatively smaller amount of publicly available evidence necessary to conclude the ultimate use of the facilities. Red camps denote minimal or incomplete evidence. Because of that lack of evidence, they have not been included in the public database.

This is not meant to suggest that the scope and scale of the system is small. Agence France-Presse (AFP) estimates there are at least 181 such facilities in Xinjiang,10 while research by German-based academic Adrian Zenz suggests there may be as many as 1,200 facilities.11

Instead, this report and its underlying database aim to create a repository of existing research into the Xinjiang camps in order to save for posterity the information that China’s censors are rapidly deleting from the public record.

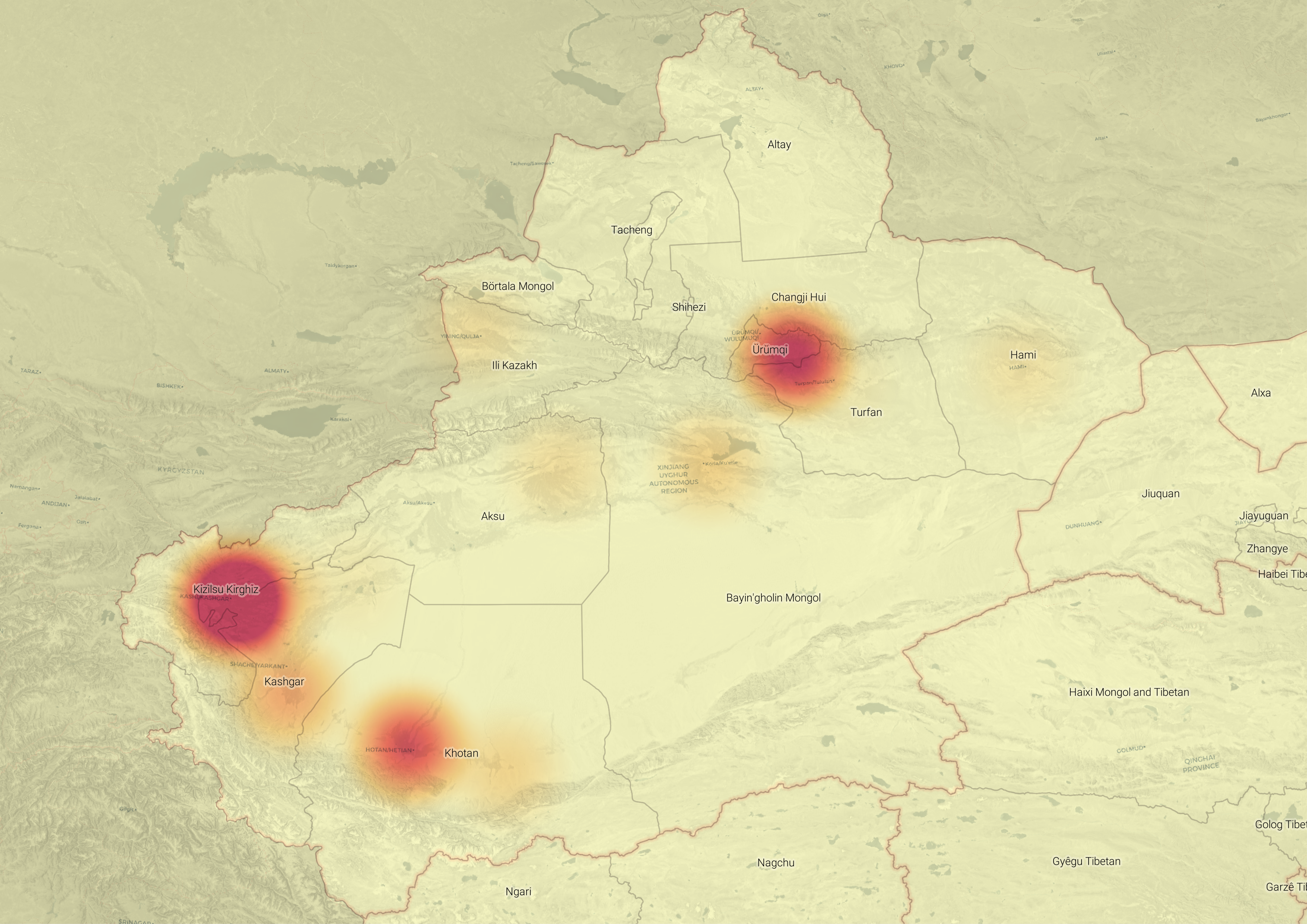

Figure 1: Heat map showing the distribution and size of the 28 camps across Xinjiang province. The larger the combined size of facilities in an area, the darker the shade on the map. Kashgar City and its surrounds feature the highest density of facility floor space and are therefore likely where the greatest numbers of re-education detainees are held.

Figure 2: The cumulative floor area in the analysed facilities. Following the second quarter of 2017, many already-constructed buildings were converted into re-education facilities (separated into camps tagged green and orange).

Figure 3: The rate of quarterly additional construction. Spikes can be seen during the summer months (third quarters) of 2017 and 2018. Growth so far in 2018 (1.169 million square metres) has already outpaced growth in the entirety of 2017 (918,000 m2).

Case studies

The devil is in the detail: The Kashgar City Vocational Technical Education Training Center12

Coordinates: 39°27'9.59"N, 76°6'34.24"E

Last month, Global Times editor Hu Xijin visited what he referred to as a ‘vocational training center’ in Kashgar. He posted a two-minute video of the trip on his Twitter account.13

Hu visited Middle School No. 4 located to the east of Kashgar City. This school, as well as Middle Schools 5 and 6, were under construction across the first half of 2017. Over the summer break, ovals at Middle Schools 5 and 6 were turfed with grass. These schools were being built adjacent to two other schools—the Kashgar City High School and the Huka Experimental Middle School (沪喀实验中学).

But by July 2017, when construction was complete, every ‘school’ building in the southwest of the facility (previously Middle School No. 5) was surrounded by tall fencing that had been painted green and topped with razor wire. By August, much of School No. 6 was enclosed with similar fencing. Upon completion in around November 2017, School No. 4 was also highly securitised and a tender was released calling for bidders to oversee and install new equipment, including a new surveillance camera system.14

In March 2018, one of the previously turfed sports ovals was demolished and replaced by four large six-storey buildings, totalling roughly 50,000 m2 of floor space. Each was surrounded by six 10-by-18 m fenced yards for detainees.

Kashgar City High School and Huka Experimental Middle School, only 50 m to the north of Kashgar Middle School No. 4, paint a dramatically different picture. Basketball courts are filled with students playing outside, and people can be seen in satellite imagery walking between buildings in the schools and on the large sports fields.

The video posted by Hu Xijin of Middle School No. 4 on 24 October shows detainees dancing and playing table-tennis and basketball. However, this visit—and the footage shared on social media—may not reflect the regular daily experiences of the detainees.

Through satellite and imagery analysis—including imagery updated daily—we can determine that these courts are coloured mats that are recent additions to the camp. The mats were placed on a concrete-covered area that is normally bare and appears inaccessible to detainees.

Lifted edge of the basketball mat suggests that these courts are likely not permanent.

Across 25 satellite images between August 2017 and August 2018, which show the facility since its construction, not a single image featured these outdoor courts. But these coloured mats do appear in satellite imagery available from 10 October. Global Times editor Hu Xijin posted about his visit to these facilities on Twitter and Weibo on 24 October.15

The location filmed by Hu Xijin in Kashgar City Vocational Technical Education Training Center. Features outlined in the panorama produced from Global Times reporting correspond to outlines in the same colour in the satellite imagery.

Checking in with the Shule County Chengnan Training Center since the Economist’s May 2018 coverage16

Coordinates: 39°21'27.64"N, 76°3'2.39"E

On 31 May 2018 the Economist included satellite footage of the ‘Shule County Chengnan Training Center’ in a lengthy article it published on China’s ‘apartheid with Chinese characteristics’.17

We have tracked this camp’s enormous growth since the Economist article featured satellite imagery of the camp. Since March 2018—which was the date the satellite image was taken from—the facility has more than doubled in size.

Across the 2.5-year time period covered in this report,18 the facility has grown from 5 to 24 buildings or wings. Its total floor size has increased during that period from 12,200 m2 to 129,600 m2. This represents an increase in size of 1062.3%.

The camp is described in official documents as a ‘transformation through education’ facility, and a tender shows the involvement of the Shule County Justice Bureau.19 Through satellite and imagery analysis, the camp’s physical features—including barricaded facilities, watchtowers, and enclosures surrounded by barbed-wire fencing—can be clearly seen.

But the evidence base for this facility goes beyond satellite imagery, tenders and floor sizes. In addition, we have matched our satellite images to the first-hand accounts, street-view imagery and video footage published by religious freedom advocacy group Bitter Winter in September 2018.20

Bitter Winter’s evidence highlights several key features of the facility. Footage from newly constructed buildings shows the scale of the camp. The reporting detailed the structure of these facilities. Each floor consists of 28 rooms, and each room is monitored by two security cameras.

Footage acquired by Bitter Winter of the Chengnan Training Centre. Features outlined in the photos correspond to outlines in the same colour in the satellite imagery.

Methodology

This report provides a quantifiable picture of the spread and growth of China’s large network of camps throughout the Xinjiang region. These camps were located through various means, including via unique satellite signatures and physical features; official construction bidding tenders from the Chinese government; and media collected from official sources, local and international NGOs, academics and digital activists. Considerable information was drawn from the analysis of freely available or commercial satellite imagery.

Satellite imagery of these camps shows highly securitised facilities with features such as significant fencing to heavily restrict the movement of individuals, consistent coverage by watchtowers, and strategic barricades with only small numbers of entry points. Often the perimeter around these camps is multi-layered and consists of large walls with tall razor-wire fencing on both the inside and outside. These features allowed us to pinpoint the location of camps mentioned in official construction tenders.

Locating camps was aided significantly by engaging and sharing information with Shawn Zhang, a student at the University of British Columbia.21 In addition, official media and reporting by NGOs and activists were vital. These sources provided media from some facilities which allowed us to match the features shown—such as buildings and fencing—with the available satellite imagery.

The floor area of every facility was measured.

The growth in floor area of these facilities was calculated for every quarter from the beginning of 2016 to September 2018. In most cases, this process involved measuring the roof area of every building using Google Earth imagery and other commercial satellite imagery collected by Digital Globe. Floor area was then calculated by multiplying roof area by the number of storeys in each building. The number of storeys was estimated from satellite imagery by either counting the externally visible windows when the building’s facade was shown or, when the facade was not prominently featured, by analysing the length of the shadows cast by the building. Where footage of these buildings from the ground existed, this was used as the primary source for the number of storeys.

Some facilities contained additional buildings that were constructed after the most recently available Digital Globe imagery. For these cases, the floor area was calculated from lower resolution (3 m pixels as opposed to 30–50 cm pixels) imagery provided by Planet Labs.

No attempt was made in this analysis to differentiate between buildings used for different purposes, and the total area of each facility includes teaching buildings, administrative buildings and dormitories that house detainees.

In addition, no attempt was made to determine the date of a facility’s first use as a re-education facility. For facilities such as schools or government-built residential housing that have been converted to re-education centres, our measurements represent the total building area within the current facility’s boundaries.

These measurements were translated into chronological growth by cross-referencing building measurements with monthly satellite imagery accessed through Planet Labs’ Explorer portal to determine the period of time over which each building was constructed or completed. Some buildings that were too small to register in Planet Lab’s lower resolution imagery, such as single-storey utility buildings or sheds, were not included in this analysis. This data can be found in the database accompanying this report.

Facilities were then matched to publicly available construction tenders released by local governments using Chinese-language web-searching and links collected by other researchers (chiefly, Adrian Zenz, a China security expert at Germany's European School of Culture and Theology). Saving this information often involved a race against time to gather the data before the documents were removed by those censoring China’s cyberspace. Every important document discovered and included in our database was permanently archived online.

Finally, the report drew on media reporting in local, national and international outlets. This media collection—including photographs, videos and geographical data—was used to further confirm key details such as the location, use or purpose, and physical features of each facility.

Conclusion

The speed with which China has built its sprawling network of indoctrination centres in Xinjiang is reminiscent of Beijing’s efforts in the South China Sea. Similar to the pace with which it has created new ‘islands’ where none existed before, the Chinese state has changed the facts on the ground in Xinjiang so dramatically that it has allowed little time for other countries to meaningfully react.

This report clearly shows the speed with which this build-out of internment camps is taking place. Moreover, the structures being built appear intended for permanent use. Chillingly, stories of detainees being released from these camps are few and far between.

Without any concerted international pressure, it seems likely the Chinese state will continue to perpetrate these human rights violations on a massive scale with impunity.

Acknowledgments

ASPI ICPC would like to thank Dr Samantha Hoffman and Alex Joske for their contributions to this research.

This project would not have been possible without the crucial ongoing work of Shawn Zhang, Adrian Zenz, journalists and civil society groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment