By Fabrizio Tassinari

EU defence cooperation suffers from a lack of strategic purpose. This challenge offers an opportunity for smaller members such as Denmark to stress that PESCO supported by Germany and the French EI2 initiative are not and should not be competitive models.

Modern German defence policy is mired in a paradox. While international partners expect more activism from Germany, a majority of its citizens believes that international organizations are more competent than the government in the field of defence and armament policy. To address this dilemma, the notion of a European Army has repeatedly been stated to be a central long-term goal of German defence policy.

This goal, however, appears far-fetched, if not downright disingenuous, and not only because of the hesitations of Germany’s European partners. In 2015, Chancellor Angela Merkel herself questioned its realization, citing concerns that Germany’s Constitutional Court would rule against it, as defence forms the core parts of German national sovereignty. In light of Brexit and the NATO-bashing by U.S. President Donald Trump, Merkel has acknowledged the need for EU’s strategic autonomy. However, austerity measures have affected the Bundeswehr’s operative capabilities to such a degree as to hamper Germany’s ambitions and overall reputation in international military cooperation.

Recommendations

EU partners expecting increasing military activism from Germany should remember that the fractioning in the Bundestag could make it harder for them to intervene abroad.

European defence cooperation and the Franco-German motor within it, remains tactical rather than strategic. This approach does not benefit smaller EU members such as Denmark.

Denmark’s specific position provides an opportunity to call for a more streamlined approach. The European Parliament election is an occasion to bring this to the fore as part of a broader moderate- conservative platform on European security.

PESCO and the European Intervention Initiative from a German perspective

By fostering closer cooperation among armed forces in Europe, Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) has been presented as the chief EU effort to face global threats in the 21st century. However, in order to take the various national sensitivities and security priorities in Europe into account, it has been designed without a clearly identified end-goal. It was precisely the glacial pace of European decision-making that raised French concerns about PESCO’s operational capability in time-sensitive crisis situations. To address this problem, President Macron of France launched the European Intervention Initiative, EI2, which proposes to function outside of EU-structures. The French initiative is analysed not as a call for new structures, but for a flexible and exclusive grouping of states that are willing and able to take action, whether they are members of the EU or not. With PESCO perceived as falling short of providing resources and operational capacity, EI2’s central priority is the development of the capable military cooperation alliance that France needs to cope with its military challenges.

The German government was initially averse to the proposed initiative: Germany’s goal of repairing fractured lines between groups of member states (which PESCO would achieve) is seen as threatened by cooperation models that function outside of EU-structures.

However, rejecting the idea could have been seen a blatant affront to their supposedly closest ally. With Germany already putting a brake on many of Macron’s European reform ambitions, Merkel could not risk tarnishing the image of the Franco-German engine further, especially when one considers that a majority of Germans support closer relations with France. What is worse, a German “nein” would be unlikely to stop Macron’s project. By joining the initiative, Merkel has avoided accusations of sabotaging Macron’s initiative, while retaining some leverage for Germany in the long run, and continuing to exercise influence while supporting PESCO as the main framework for security cooperation in Europe.

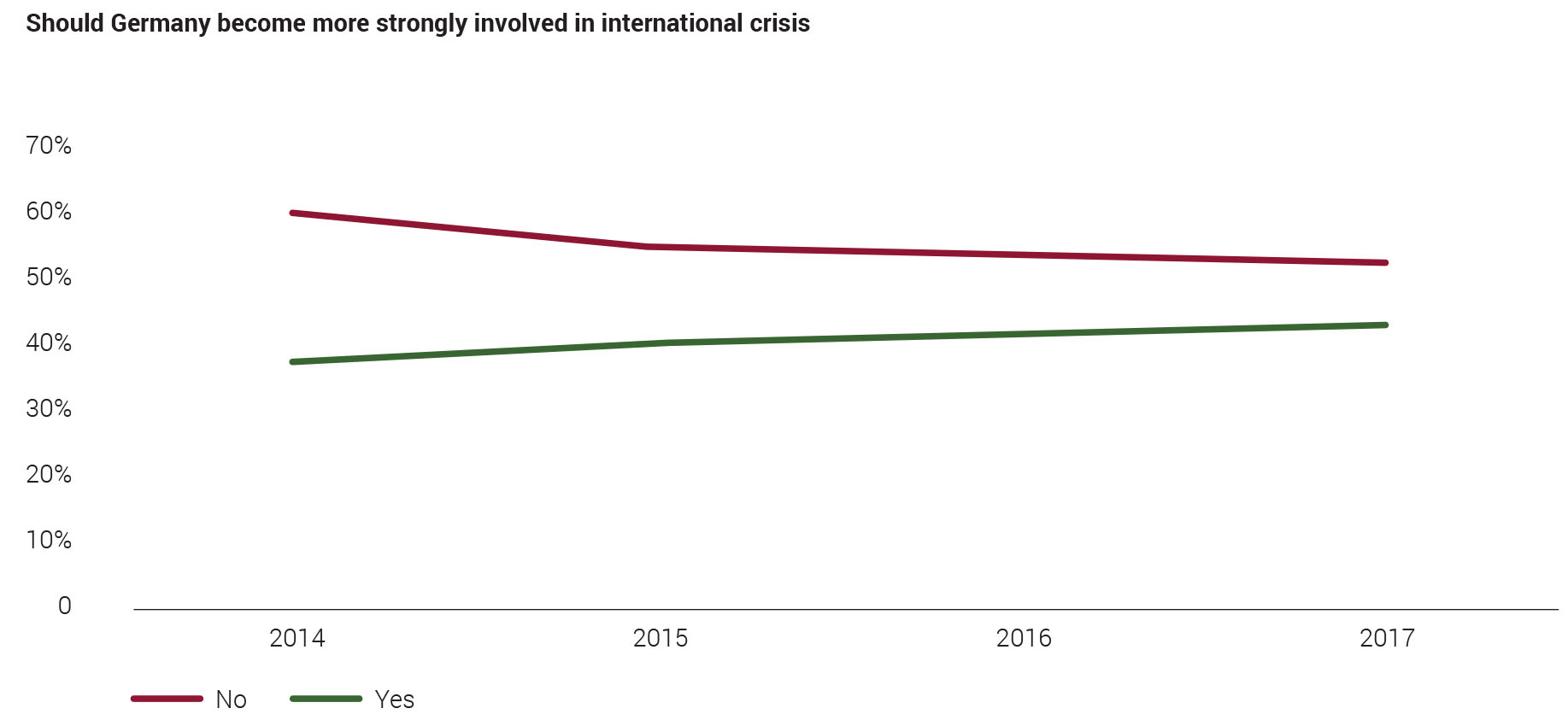

As a result, Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen described the EI2 military alliance as a forum of like-minded states that could cooperate to identify crisis scenarios at an early stage and develop political will. Merkel officially welcomed Macron’s initiative to develop a common strategic military culture, but not without stressing that PESCO is the decisive step in creating a common security policy for Europe. Chancellor Merkel also underlined the importance of embedding a potential intervention force in existing structures of security cooperation. She also stressed that joining the initiative does not change the Bundeswehr’s character of a “parliamentary army”, hereby linking any decision to send troops abroad to obtaining the approval of the Bundestag, ensuring that Germany is not bound to participate in every mission. In doing so, she considered the preferences of vast parts of the population who still reject the idea of Germany becoming more involved militarily.

Source: Involvement or Restraint? Survey summaries on German attitudes to foreign policy commissioned by Körber-Stiftung 2014 – 2017. Click image to enlarge.

The Perils and promise of a Janus-faced approach

The caution and continuing ambivalence surrounding Germany’s defence posture warrants a number of responses from its European partners. It particularly requires one from Denmark, which, limited in its room for manoeuvre by the defence opt-out and supporting Macron’s EI2, continues to regard Germany as a rising and reliable strategic partner.

The first consideration in this respect is the persistent gap between the partners’ expectations and the actual degree of activism and “will to power” of the German government. While joining all initiatives pertaining to growing cooperation in Europe, the Chancellor herself is wary and realistic about the extent to which domestic and external constraints will enable Germany to play the much looked-for leadership role. Germany having a “parliamentary army” and the currently fractious situation in the Bundestag will make it harder for Germany to intervene abroad.

Secondly, recent experience suggests that France and Germany do not see eye to eye on the future of European defence cooperation. The long-awaited impetus of France and Germany is not yet at cross-purposes but it is sending mixed signals about the extent to which Paris and Berlin want to place joint political weight behind new initiatives. At best PESCO and EI2 could complement each other in terms of membership and operational focus. But much more likely, they will remain mired in tactical manoeuvring, tiptoeing around national sensitivities and sidestepping the strategic imperatives that require closer defence cooperation in the first place.

Germany has a PESCO-first approach; in light of its EU opt-out on defence, Denmark must put its weight behind the French EI2. In light of Brexit and Trump’s increasingly critical pronouncements on NATO and European security, Germany has become Denmark’s most significant and like-minded European partner. It falls on Copenhagen, with an irregular position in the European defence policy architecture, to underline that PESCO and EI2 do not and should not present smaller countries especially with competitive models of European defence cooperation. Denmark’s relative “equidistance” from Paris and Berlin, and its historically strong activism in foreign and defence policy, place it in a favourable position to search for comparative advantages and complementarities. Momentum for this argument could be fruitfully developed, as part of a broader moderate-conservative security platform of the European People’s Party and Macron’s own group ahead of the upcoming European Parliamentary election campaign.

German Coalition Agreements – Statements about a European Army

2017 – We will fill the European defence union with life. In doing so, we will push ahead with the projects brought into PESCO and use the new instrument of the European Defence Fund. We are working for a properly equipped EU headquarters to lead civilian and military missions. We want the planning processes within the EU to be coordinated more efficiently and harmonized with those of NATO. The Bundeswehr remains a parliamentary army within the framework of this cooperation. We will take further steps towards an ”army of Europeans”.

2013 – Together with our allies, we want to strengthen weak skills and increase resilience. We are seeking an ever-closer alliance of European forces, which can evolve into a European army controlled by parliament.

2009 – We want to work for the further development of the common European security and defence policy. The long-term goal for us is to build a European army under full parliamentary control.

About the Author

Fabrizio Tassinari is a Senior Researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS).

No comments:

Post a Comment