By Catherine Putz

“Synergizing” China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) remains in the rhetoric of both sides, most recently while Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was in Beijing for the 23rd China-Russia Prime Ministers’ Regular Meeting. His Chinese counterpart, Li Keqiang, according to the Chinese Foreign Affairs Ministry summary, said that “China will synergize the Belt and Road Initiative and the Eurasian Economic Union.”

“Synergizing” China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) remains in the rhetoric of both sides, most recently while Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was in Beijing for the 23rd China-Russia Prime Ministers’ Regular Meeting. His Chinese counterpart, Li Keqiang, according to the Chinese Foreign Affairs Ministry summary, said that “China will synergize the Belt and Road Initiative and the Eurasian Economic Union.”

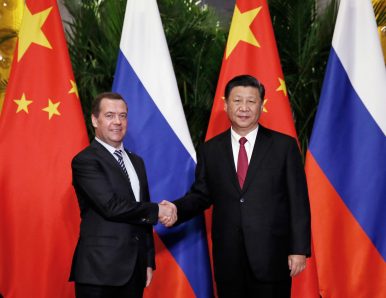

Medvedev was also in Beijing to be a guest of honor at China’s first International Import Expo (CIIE). The readout of his meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping didn’t mention the EAEU but did stress cohesion between China and Russia:

Both China and Russia are in a crucial stage in achieving national development and revitalization, Xi said.

Facing an unprecedentedly complex international environment, it is more important to keep bilateral ties at a high level and reinforce strategic coordination between the two countries, Xi said.

He said a priority for the two sides’ work in the next phase is to comprehensively implement the consensus between him and Russian President Vladimir Putin on practical cooperation between the two sides.

Though light on details, the message is clear: Russia and China stand together.

The idea of “linking” the EAEU and the BRI (at the time called the Silk Road Economic Belt), arose in May 2015, a few months after the EAEU was officially established. Xi was in Moscow to attend the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, or the Great Patriotic War, as it’s known in Russia. Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin reportedly agreed at the time to “connect the initiative of the construction of the Silk Road Economic Belt put forward by the Chinese side with the construction of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) of the Russian side.”

In July 2015, at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Ufa, Russia, a Chinese diplomat briefing reporters said Xi and Putin had discussed concrete projects to combine their respective economic projects. TASS reported at the time that the Chinese diplomat said the SCO would serve as a “convenient floor for integrating the implementation of those two projects.”

When convenient, the linking of the BRI and the EAEU is mentioned by Russian and Chinese leaders. It generates in the mind the image of two global giants hitching together their prized economic projects. In the subsequent years, however, here hasn’t been much clarity on what either side really means when they mention this connection. In the meantime, the BRI remains as amorphous as ever — anything can be a BRI project if the Chinese say it’s a BRI project. The EAEU, in contrast, putters along, inspiring neither confidence nor much increased economic activity. The EAEU as a prestige-generating project for Russia has fallen relatively flat.

In November 2016, Cholpon Orozobekova, writing for The Diplomat and pondering the connection between Russia and China, commented that “Although Chinese sources are describing this partnership as a real game changer, the integration initiative has taken no concrete steps so far; it is only in the consultation phase.”

A further two years on, tangible progress still remains largely locked in rhetoric. In May 2018, a Sino-EAEU agreement was signed with the expectation that it will enter into force in early 2019. As Gregory Shtraks noted in an analysis for the Jamestown Foundation, a Xinhua report cited the chairman of the board to the Eurasian Economic Commission, Tigran Sargsyan, saying that the treaty “creates a serious legal framework for the interaction of businesses and makes the environment in which they will operate predictable.” What that specifically means remains unclear.

Arguably the entire point of touting the linkage of the BRI and the EAEU has been political. Nargis Kassenova, a senior fellow at Harvard University’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, argued as much in a recent piece for the Foreign Policy Research Institute. In March 2017, she notes, “the Eurasian Economic Commission prepared a list of 39 priority projects to support the linkage, including building new roads, modernizing existing ones, creating logistics centers, and developing transport hubs.” The list was not made public but among the projects cited by officials as on the list — the Western Europe-Western China motorway, Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway, and China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway — Kassenova writes, progress is slow and EAEU involvement questionable.

“Such shallow progress in linking the EAEU and BRI indicates that its function is mostly rhetorical, signaling the intention of Russia and China to accommodate each other’s ambitions in Central Asia,” Kassenova writes. Central Asian states, certainly aware of the risks of dealing bilaterally with China, see few other options. Russia can’t provide the economic development support they require, and China can.

Beijing and Moscow will continue to tout the connection of the BRI and the EAEU for the simple reason that doing so satisfies the political needs of both sides.

No comments:

Post a Comment