BY CCHRISTINEFAIR

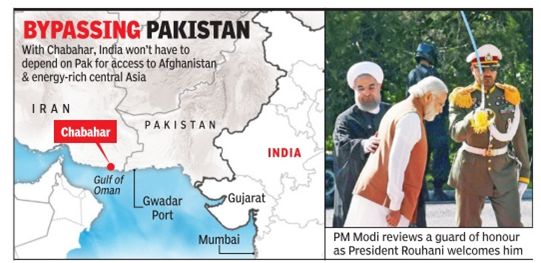

When the imposturous Donald Trump assumed the U.S. presidency in January 2017, he resolved to undo Obama’s legacy whether it was domestic achievements such as healthcare for all or the historic rapprochements with Cuba or the Iran-specific Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). As promised, in May 2018, Trump withdrew from the so-called JCPOA and threatened sanctions upon anyone dealing with Iran. This discomfited India in particular for several reasons. First India imports more than 80% of crude of which about 10% comes from Iran. Indian refiners prefer Iranian crude due to better pricing and terms compared to other suppliers. Second, India is set to develop of one of three berths at Iran’s deep-sea port at Chabahar, which would also come under sanctions. India is also working to build a rail link from the port to the Afghan border. Not only would these sanctions strain India’s strategic goals, but it would also call into question the economic viability of the port which, in turn, would have deleterious consequences for Afghanistan, which needs access to ports other than those in Pakistan.

When the imposturous Donald Trump assumed the U.S. presidency in January 2017, he resolved to undo Obama’s legacy whether it was domestic achievements such as healthcare for all or the historic rapprochements with Cuba or the Iran-specific Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). As promised, in May 2018, Trump withdrew from the so-called JCPOA and threatened sanctions upon anyone dealing with Iran. This discomfited India in particular for several reasons. First India imports more than 80% of crude of which about 10% comes from Iran. Indian refiners prefer Iranian crude due to better pricing and terms compared to other suppliers. Second, India is set to develop of one of three berths at Iran’s deep-sea port at Chabahar, which would also come under sanctions. India is also working to build a rail link from the port to the Afghan border. Not only would these sanctions strain India’s strategic goals, but it would also call into question the economic viability of the port which, in turn, would have deleterious consequences for Afghanistan, which needs access to ports other than those in Pakistan.

Under the US law which prescribes these sanctions, Washington could exempt sanctions for activities that “provide reconstruction assistance for or further the economic development of Afghanistan.” Many analysts, including this author, strenuously argued that India should push for and ultimately receive sanction relief. India stood its ground on all counts and, consequently, the Trump administration offered India a waiver on both oil imports and Chabahar developments, including the railway linkage. This is welcome news not only for India but also for Afghanistan. However, more needs to be done to make Chabahar the much-needed economic life-line of Afghanistan.

Indo-Iranian Relations: The Big Picture

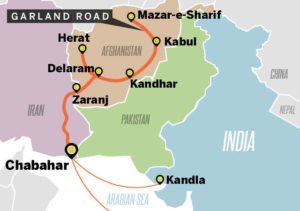

In 2003, India and Iran signed the so-called “RoadMap to Strategic Cooperation.” This was a foundational document that put forward the key activities that would guide the most recent bilateral effort at rapprochement, which began in the mid-1990s under India’s then Prime Minister Rao and Iran’s President Rafsanjani but foundered with few tangible gains. One of the prominent elements of the 2003 agreement was the collaboration on Iran’s deep-sea port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman. India is a stakeholder in the related so-called North-South Corridor per which goods move from Chabahar and travel through Iran on rail or road, then onward to the Caspian and beyond to northern markets. For India, Chabahar offers a lifeline to Iran, Afghanistan, the Central Asian States and beyond. Moreover, it is situated a mere 171 kilometers from Gwador, the port that China is building on Pakistan’s Makran coast in insurgency-prone Balochistan as a part of the so-called “China Pakistan Economic Corridor.”

In 2005, India also began building an ambitious road project that linked Afghanistan to Iran known as Route 606 or the Delaram–Zaranj Highway inside Afghanistan. The 215-km, two-lane road, connects Zaranj (the dusty provincial capital of Afghan’s Nimruz province bordering Iran) to Delaram, a transport hub in Nimruz that connects to the Kandahar–Herat Highway, which is part of the Ring Road that connects most of Afghanistan’s major cities. Built by the Border Roads Organization (BRO) at a cost of Rs.600 crore, it was a constant antagonism to Pakistan for several reasons.

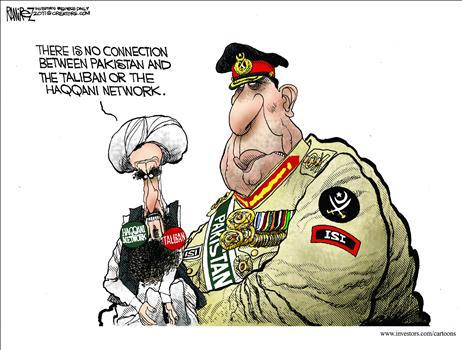

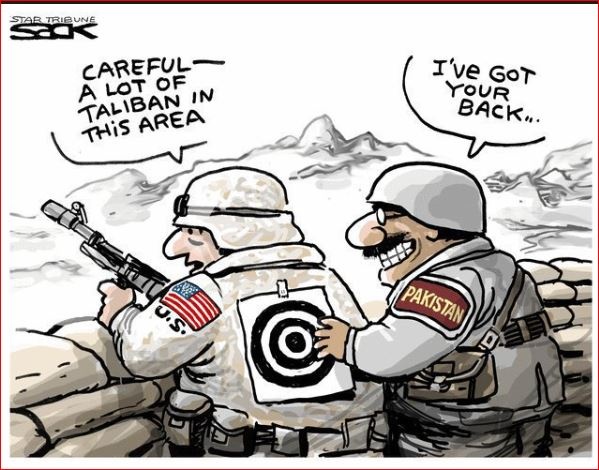

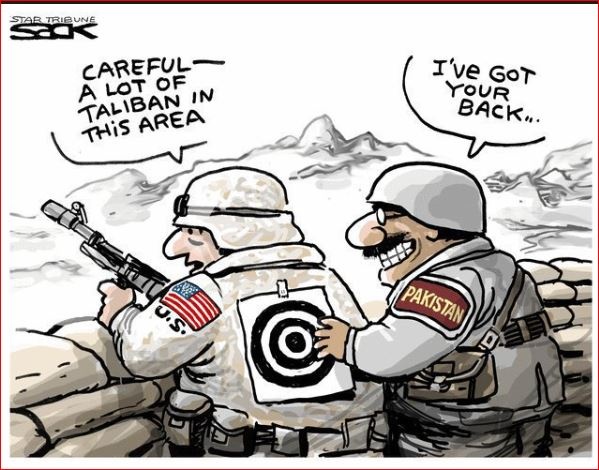

First, is the nature of the BRO itself, whose own website explains that it is “committed to meeting the strategic needs of [India’s] armed forces.” Over the lifetime of the project, over 300 BRO engineers and technicians were deployed on the project, accompanied by 70 Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) personnel for the security of BRO personnel. Second, Pakistan understood that this route would help eliminate Afghanistan’s dependence upon Pakistan for access to warm waters. Pakistan has long used Afghanistan’s dependence upon Pakistan as a tool of economic arbitrage and to preclude India from having ground access to Afghanistan. Third, Nimruz borders the restive Pakistani province of Balochistan, where Pakistan has long accused India of interfering in collusion with Afghanistan. Forth, it was yet another visible symbol of India’s presence in a country that Pakistan seeks to render into a vassal of Rawalpindi, the home of Pakistan’s opprobrious army. Given Pakistan’s enormous control over the Taliban and other murderous organizations such as the Haqqani Network, the road came under constant attack during its construction and after it was handed over the Afghans in January 2009, by which time some six Indians, including BRO driver and four ITBP soldiers, as well as 129 Afghans were murdered. This road was to be the shortest route to move products between Afghanistan and Iranian ports.

After the U.N. Security Council imposed Chapter VII sanctions on Iran in 2006, India retrenched from the project ceding space to China. In 2015, under President Obama, China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States along with the European Union forged a historic deal with Iran to limit its ability to develop nuclear weapons while bringing Iran back into the comity of nations. The so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) cleared the path for India to re-engage in Chabahar. India resumed work with alacrity because this port is critical for India’s own access to markets in Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia but also for Afghanistan’s own economic survival, in which India is a key stakeholder. With the sanctions waiver on hand, India should move to deepen its commitment Chabahar and Afghanistan’s economic future.

After the U.N. Security Council imposed Chapter VII sanctions on Iran in 2006, India retrenched from the project ceding space to China. In 2015, under President Obama, China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States along with the European Union forged a historic deal with Iran to limit its ability to develop nuclear weapons while bringing Iran back into the comity of nations. The so-called Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) cleared the path for India to re-engage in Chabahar. India resumed work with alacrity because this port is critical for India’s own access to markets in Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia but also for Afghanistan’s own economic survival, in which India is a key stakeholder. With the sanctions waiver on hand, India should move to deepen its commitment Chabahar and Afghanistan’s economic future.

A New Way Forward for Afghanistan?

While the United States is hopeful that it can come to some form of negotiated settlement with the Taliban which would conclude the endless war in Afghanistan, long-time observers of South Asia are skeptical that efforts will fructify. Why would the Taliban negotiate an end when the Taliban need not defeat the Americans and their Afghan allies? The Taliban only need to keep fighting to demonstrate that the Americans and Afghans cannot defeat them. The is the very definition of an insurgent’s victory. Second, why would Pakistan allow the Taliban to sue for peace unless that peace meant Afghanistan’s capitulation to Pakistan with the former serving as the latter’s suzerain? Would Afghans—who loathe Pakistan for the decades of devastation it has wrought—ever agree to such peace terms?

Whatever happens with respect to ending decades of conflict, Afghanistan needs a new way forward and I contend Chabahar—and Indian investment there—is central to this new future.

Contemporary Afghanistan is not the Afghanistan of 2001. Today, Afghanistan is connected to railheads with Iran, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. These railheads are key to helping Afghanistan get its valuable resources out of the ground and to international markets. Whereas Afghanistan was once virtually dependent upon Pakistan, it no longer is. Between 2012 and 2016, Afghan imports from Iran totaled $1.3 million compared $1.2 million from Pakistan and $1.1 million from China. While Pakistan was the largest destination for Afghan exports between 2012 and 2016 with $283 million of goods, India was right behind in the second position with $230 million. This will likely increase as Chabahar comes online. In fact, over the last year, India has shipped about 110,000 metric tons of wheat and 2,000 tons of pulses from India to Afghanistan through Chabahar over numerous shipments, demonstrating the utility of this shipping route.

If Afghanistan can focus on improving the political, economic, and trade ties with its near and far neighbors, Afghanistan can literally work around Pakistan by ever-more diminishing its dependence upon its murderous neighbor to the east. When Afghanistan is completely independent of Pakistan, it will be in a greater position to extract political concessions it.

This does not mean that Afghanistan will become peaceful. Far from it. Pakistan will work assiduously to undermine these efforts. But it does allow Afghanistan to move forward, to prosper, and to work towards economic sufficiency while strategically isolating Pakistan in every way possible that is not terribly dissimilar from the strategic decisions that India has made. India has, over successive administrations, understood implicitly that Pakistan will continue to kill Indians. However, every Indian leader since Kargil has understood that it has much to gain by avoiding war with Pakistan.

This policy of strategic restraint has paid dividends: India’s long span of economic growth has enabled it to invest in defense modernization, to diminish the immiseration of Indian masses, make human capital investments, and diversify and fortify its complex portfolio of strategic alliances. This has not been cost-free: every year, Pakistan’s proxies murder dozens of Indians. In contrast, 3 Indians die every ten minutes from road accidents. In 2017 alone, 147, 913 persons died, which is many times more than the totality of Indian lives claimed in all of India’s wars with Pakistan, including Pakistan-sponsored terrorism in Kashmir. Even in Afghanistan—which is an active war zone–traffic accidents kill more civilians (nearly 5,000 in 2017) than the anti-government forces or friendly fire (3,438 in 2017). My intention here is not to trivialize either kind of death in either India or Afghanistan; rather put them into perspective and to argue that progress can continue of some fronts even though Pakistan remains committed to murdering citizens of both countries.

India is Needed Now More Than Ever

I recently traveled to Zaranj, on the border of Iran, linked Afghanistan the road built by India. I wanted to assess the infrastructural capacity and traffic through this border crossing. What I found there shocked my interlocutors in Kabul, many of whom were under the impression that this crossing is under-utilized. Far from it. This dusty town was a busy hub and at full capacity even though little traffic is coming in from Chabahar at present: most of the traffic is coming from Iran’s more established port at Bandar Abbas. If India hopes that this route will become a significant alternative to Pakistan’s routes to warm water, India should consider helping Afghanistan augment and expand the infrastructure here.

For one thing, the bridge that links the two countries is too narrow to permit two-way traffic. It takes interminably long for a single truck to make the crossing. For years, a two-way bridge has been promised but has not yet materialized. Trucks are stacked up along the theZaranj-Delaram highway, making it difficult for regular traffic. Trucks may have to wait in line, clogging up the narrow road, for up to two months as they await their turn to cross. The customs and border facilities at Zaranj struggle with the current operational tempo as does the counter-narcotics forces who witness large amounts of precursor materials that convert opium in lucrative narcotics like heroin but lack large-scale detection devices. As I spent two days in Zaranj speaking with drivers, businessmen and an array of officials, I could not imagine how this crossing could bear more traffic. My interlocutors agreed.

Once in Iran, Afghan truckers report a bevy of woes beginning with usurious visa charges, extortion, and inadequate quotas of petrol to make the journey. Truckers told me that they feel as if they have no advocates. Everyone said that they wish the border could be open all day, every day; however, they claim the Iranians demure for various reasons. Truckers who transport goods into Afghanistan from Zaranj must countenance the Taliban as well as corrupt Afghan police, seeking payments along their routes. If Afghanistan is to derive maximal benefit from this strategic border crossing, it will have to dedicate more resources to clean up corruption and enhance security and work with Iran to make life easier for those using the crossing. Presumably, both stand to benefit from doing.

While the twinned problems of corruption and insecurity perdure throughout Afghanistan, Kabul should prioritize this crossing more than it has to date. It has the potential to transform this dusty little outpost with few opportunities other than trucking and hocking smuggled fuel. India, which enjoys good relations with Iran and Afghanistan may be well positioned to help on all these fronts. In doing so, India will advance its own strategic interests in the region all the while continuing to provide the value-added projects that make ordinary Afghans’ lives all the more livable and which have endeared Indians to Afghans.

The writer has authored the books Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (OUP, 2014) and in their Own Words: Understanding Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (Hurst 2018).

Versions of this blog post have been published by Khaama Post, on 22 November 2018 at:https://www.khaama.com/a-new-strategy-for-afghanistan-begins-in-iran-070809/

No comments:

Post a Comment