The United States has indicated on October 20, that it will withdraw from the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, with President Donald Trump saying Saturday that Russia has been “violating it for many years,” and “we’re not going to let them violate a nuclear agreement and go out and do weapons and we’re not allowed to.” But despite pinning the blame on Moscow’s repeated violations of the treaty (Russia having allegedly begun test flights of a prohibited cruise missile as early as 2008), America’s withdrawal from the INF Treaty is not really about Russia—nor is it even about nuclear weapons. As with much else in its new era of strategic competition, America’s move is focused squarely on its contest with China in the Asia-Pacific region.

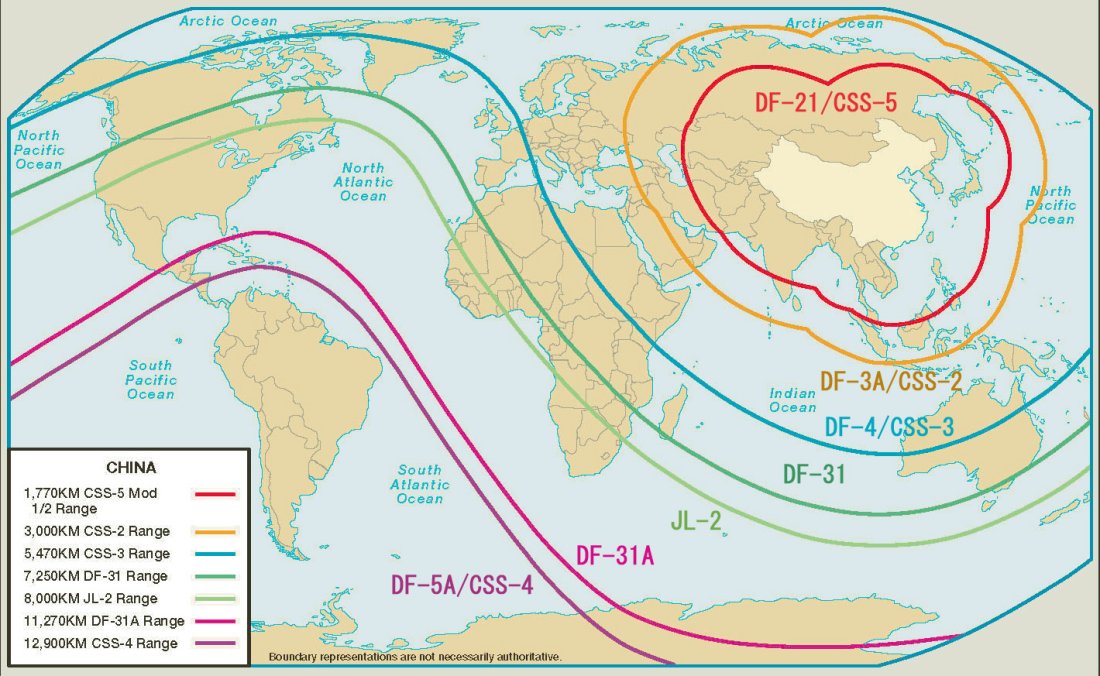

China has never been a signatory of the INF Treaty, which bans the development or deployment of both nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers. This has allowed China to build up a vast arsenal of conventional anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) weapons, such as the DF-21 “carrier killer” anti-ship ballistic missile (range of 1,500 kilometers). All of these weapons are of a class that the United States is legally prevented from deploying.

This has led to America becoming significantly “out sticked” in the ongoing “ range war " between military systems designed to safely control the increasingly unfriendly seas and skies of the Western Pacific. In the event of a high-end conflict, U.S. naval surface combatants would find themselves at a disadvantage, having to rely on older sea-launched standoff systems, like the Tomahawk land-attack missile, and vulnerable carrier-based airpower, to strike at deadly A2/AD weapons that can hide within the Chinese interior.

This is a problem, because as Christopher Johnson, formerly the CIA’s senior China analyst, recently told The Economist “In any air war we do great in the first couple of days,” but “then we have to move everything back to Japan, and we can’t generate sufficient sorties from that point for deep strike on the mainland.” And without being able to strike anti-ship systems in the mainland, American carriers operating off the Chinese coast would be placed in unacceptable danger.

U.S. withdrawal from INF, however, could help reverse this dynamic and lead to a nightmare scenario for China.

New American conventional systems, probably beginning with a ground-launched version of the Tomahawk but perhaps eventually expanding to include ballistic missiles similar to the DF-21 and DF-26, could be stationed in unsinkable, out-of-the-way locales like northern Japan, Guam, the southern Philippines, or even northern Australia.

These weapons would have the potential to act as the cornerstone of an alternative U.S. military strategy for the Western Pacific increasingly advocated by defense experts in Washington. This new strategy would use America’s own A2/AD systems to lock down the waters within the “first island chain” and transform China’s near seas into what scholars like Michael Swaine and others havedescribed as a “no man’s land” in the event of war. Such a strategy, labeled by Andrew Krepinevich as “ Archipelagic Defense ,” would be capable of deterring and containing Chinese military aggression without having to place U.S. surface vessels at significant risk. Moreover, such a strategy has the potential to be significantly cheaper (in both money and lives) than relying on incredibly expensive carrier battle groups to maintain sea control.

Chinese strategists have long been deeply concerned about the potential for such a scenario, in which the defenses of America and its regional allies would prevent the Chinese navy from “breaking through the thistles” of the first island chain’s unfavorable geography, leaving China unable to project maritime power beyond its near seas.

Meanwhile, many arms-control analysts have warned with dismay that U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty could provoke a new “missile race,” while Russian politician Aleksey Pushkov has declared that such an exit would be a “powerful blow inflicted on the world’s entire system of strategic stability.” However, at least in the U.S.-China context, the result could be more strategic stability rather than less, for two reasons.

First, if America followed the Archipelagic Defense strategy outlined above, then it would have less need to move any “ too big to fail ” assets within range of Chinese weapons during a crisis. The loss of those assets would be such a traumatic disaster for America (with up to six thousand lives lost with a single aircraft carrier, for example) that any U.S. leader would feel immense pressure to immediately and dramatically escalate the scale of the conflict. Instead, cheap, unmanned long-range strike weapons could serve in their place, reducing the chance of crisis escalation.

Second, with fewer American surface ships required to operate close to China, the tactical necessity for U.S. commanders to strike Chinese missile systems within mainland China as a defensive measure would be reduced. This is significant because, as Caitlin Talmadge explains in the most recent issue of Foreign Affairs , China’s nuclear weapons are intermingled with its conventional missile forces, and it would be nearly impossible for the United States to strike at China’s conventional ballistic missiles without inadvertently destroying elements of China’s strategic nuclear deterrent. And, as she writes, when “faced with such a threat, Chinese leaders could decide to use their nuclear weapons while they were still able to,” increasing the chances of a conflict going nuclear.

No comments:

Post a Comment