Jack Thompson argues that Donald Trump’s Middle East policy represents a significant change from that of Barack Obama. For instance, in addition to isolating Iran, the president appears to be supporting the ascendancy of bloc consisting of Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United Arab Emirates. However, this agenda has emerged in piecemeal fashion rather than as part of a coherent strategy – and there are few indications that administration officials have considered the long-term implications of their approach. This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in October 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Jack Thompson argues that Donald Trump’s Middle East policy represents a significant change from that of Barack Obama. For instance, in addition to isolating Iran, the president appears to be supporting the ascendancy of bloc consisting of Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United Arab Emirates. However, this agenda has emerged in piecemeal fashion rather than as part of a coherent strategy – and there are few indications that administration officials have considered the long-term implications of their approach. This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in October 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

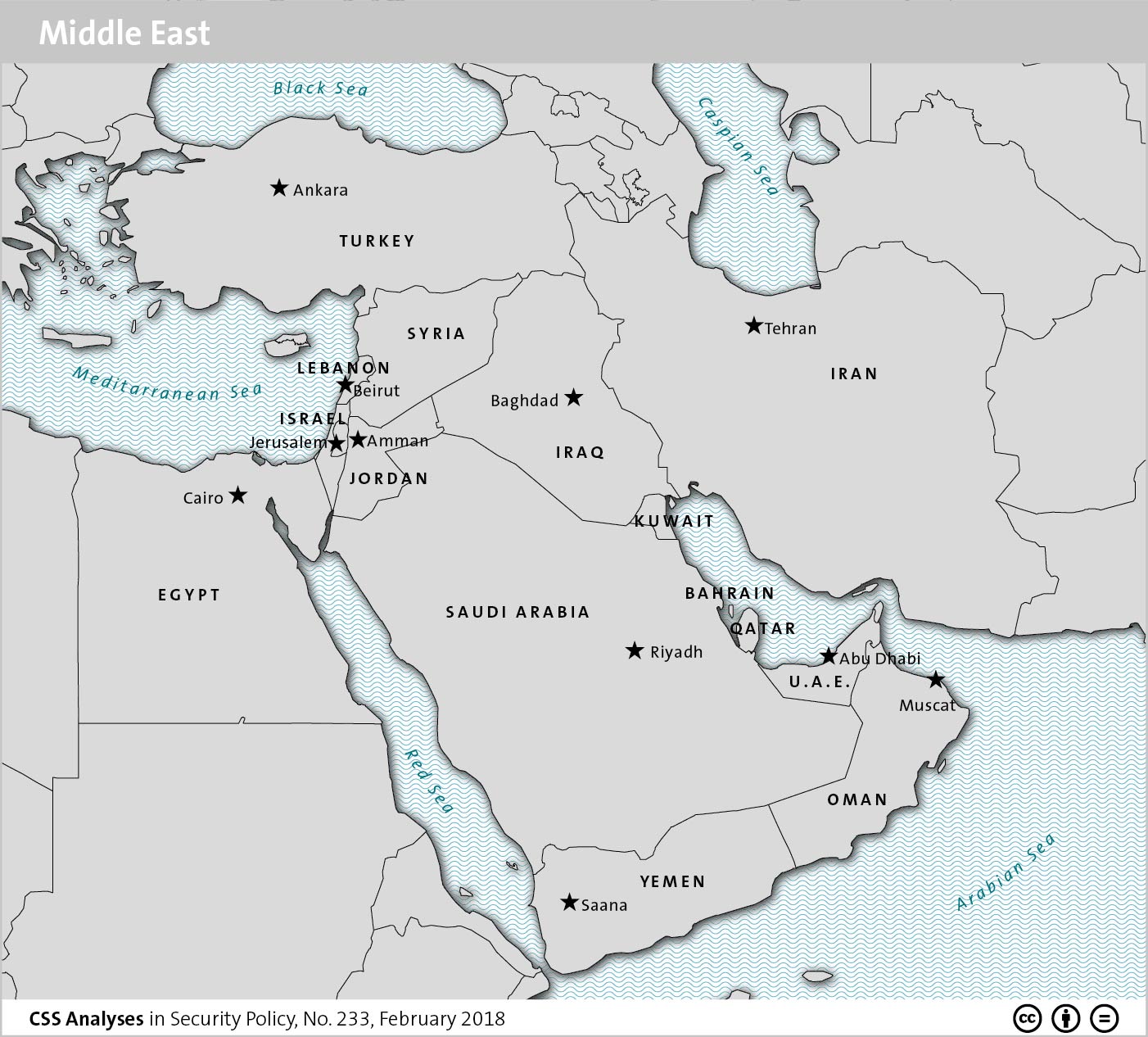

Donald Trump’s Middle East policy represents a significant change from that of Barack Obama. The president is seeking to bolster Israel and Saudi Arabia, in particular, and to isolate Iran. This agenda has emerged in piecemeal fashion rather than as part of a coherent strategy – and there are few indications that administration officials have considered the long-term implications of their approach.

Barack Obama formulated a Middle East strategy designed to repair the damage done during George W. Bush’s presidency. The United States needed to rest an exhausted military, replenish its soft power, and create political space for addressing long-standing challenges. To this end, he reduced troop levels in Iraq, avoided new large-scale military interventions, asked allies to take more responsibility for regional security, and mostly sought to address problems through diplomacy. He used a combination of engagement and sanctions to induce Iran to halt its nuclear weapons program, and sought to broker peace between the Israelis and Palestinians along lines endorsed by the international community – including a two-state solution, flexibility on the status of East Jerusalem, and pausing the expansion of Israeli settlements on Palestinian territory. To the dismay of allies such as Saudi Arabia, Obama also encouraged democratic reforms in the region, though inconsistently and with little success, and avoided overtly favoring either side of the Sunni-Shia divide.

Just as he promised during the 2016 campaign, Donald Trump has taken a different approach. Certainly, there are aspects of continuity. The president has encouraged allies to accept more of the regional security burden, resisted the temptation to send large numbers of troops to Syria and other hotspots, and – like Obama – tolerated Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen. Yet in key respects, he has departed from the policies of his predecessor. Relations with Riyadh have improved notably, whereas during Obama’s presidency the US and Saudi governments were frequently at odds. Similarly, improving ties with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, which suffered during Obama’s tenure, has been a priority. Trump has withdrawn from the 2015 deal designed to curtail Iran’s nuclear weapons program – formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA – and reinstated sanctions on Tehran. Finally, Trump has shown no interest in promoting political reform or bolstering democratic norms – as he demonstrated soon after taking office with his so-called Muslim travel ban.

US President Donald Trump walks with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud to deliver remarks in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (21 May 2017). Jonathan Ernst / Reuters

To the extent that there is a discernable pattern, it would appear that the president is promoting a bloc led by Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates, which seeks to contain Iran and to maintain the status quo vis-à-vis democratic reform and the spread of political Islam. However, there is reason to doubt that this is part of a coherent strategy.

Iran

Iran is a top concern of the administration. The 2017 National Security Strategy mentions it 17 times, and lists as a key priority in the region preventing predominance by “any power hostile to the United States” – a clear reference to Tehran. However, the administration is struggling to formulate a realistic policy in the wake of its withdrawal, in May 2018, from the JCPOA. Trump had often criticized the deal. He and other conservatives complained it did nothing to address other problematic aspects of Iranian foreign policy, including its aspirations for regional hegemony and support for radical groups such as Hezbollah. The marginalization or departure of advisers inclined to support the JCPOA – such as Secretary of Defense James Mattis, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and former National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster – and the influence of hawkish National Security Adviser John Bolton, made withdrawal more likely.

In a May 2018 speech, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the administration would be willing to restore diplomatic and economic ties in return for: complete denuclearization; cessation of Iran’s ballistic missile program; the release of all prisoners that have citizenship in the US or an allied nation; an end to efforts to extend Iranian influence in the region, especially in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan; and an end to cyberattacks.

As a basis for negotiations, this was a non-starter. Furthermore, other signatories to the JCPOA have indicated that they intend to abide by the agreement and oppose the sanctions regime. Experts have reacted with skepticism to Pompeo’s creation of the Iran Action Group, in August 2018, which the administration has billed as “an elite team of foreign policy specialists” that will seek to implement “a campaign of maximum diplomatic pressure and diplomatic isolation.” They see it as window dressing rather than a serious task force, especially because Brian Hook, a longtime Republican operative, leads it. Hook, who served as the principal deputy to former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, discontinued the traditional mission of the department’s Policy Planning Staff – offering the secretary independent, strategic advice. He has also politicized personnel decisions.

The Shia-Sunni Divide

Trump and his advisers have abandoned the longstanding policy of opposing Shia and Sunni extremism, choosing to back Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – and by extension Israel – all of which favor confrontation with Tehran. This decision risks further destabilization in the Middle East. During the 2016 campaign, Trump accused Riyadh of free riding on US security guarantees, but as president, he has given the Saudis carte blanche in the region. Saudi Arabia hosted his first foreign visit and he has ignored Riyadh’s disastrous intervention against the Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen, its crackdown on domestic dissent, its attempts to isolate Qatar, and its attempt to cow Canada after Ottawa criticized the Saudi government’s human rights record.

Most importantly, the administration is in the process of creating the Middle East Strategic Alliance – an “Arab NATO” – a proposal floated by the Saudis in the past. The goal would be to increase overall security and economic cooperation, including a regional anti-missile defense shield, and the confrontation with Iran would assume a principal role in the new alliance’s agenda. It will reportedly be announced this autumn, at a summit in Washington tentatively planned for mid-October 2018.

Analysts have speculated that Trump wants Saudi support for confronting Iran and for a Middle East peace deal. Both expectations rest upon a misunderstanding of Riyadh’s thinking. Saudi Arabia would have been willing to support a tougher line against Iran – which it views as the chief regional threat – regardless of concessions in other areas. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the Saudis would be willing to back the peace deal that Washington is trying to impose upon the Palestinians.

As the Trump administration draws closer to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, regional polarization has increased and some key actors are more distrustful of Washington. Instead of decreasing Iranian influence, US favoritism of Sunni regimes is bolstering ties between Tehran and groups such as Hezbollah and the Houthis. Iraq, which is majority Shia but which also has a substantial Sunni population, and where Iran yields considerable influence, especially among the country’s powerful Shia militias, would prefer to avoid choosing sides. It has reacted warily to overtures from Saudi Arabia and criticized US withdrawal from the JCPOA. Turkey and Qatar have also reacted increased cooperation with Tehran.

Israel and the Peace Process

Israel applauds the confrontation with Tehran, which it views as an existential threat. In fact, Israel is one of the few countries in the region that are pleased with the president’s policies. Even by the standards of previous administrations, all of which treated Israel as a close ally, Trump has gone to extraordinary lengths to please Netanyahu. This is largely a product of conservative political culture, where unquestioned support for Israel is an article of faith. The 2016 Republican Party platform called such support “an expression of Americanism” and called for policies that leave “no daylight” between the two countries.

Trump and his advisers have enthusiastically embraced this directive. In addition to withdrawing from the JCPOA, which Netanyahu castigated as a “historic mistake,” Trump moved the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem – a move long sought by the Israelis – and notified the Palestinians that their diplomatic mission in Washington will be closed. As ambassador, he sent the lawyer David Friedman, a longtime friend of the president who has been a vocal opponent of the two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict. The administration is also canceling all funding for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees – another move lauded by Netanyahu – and would like to reduce dramatically the number of Palestinians that are granted refugee status. Doing so would essentially eliminate the right of return for most Palestinians, a notable concession to Israeli hawks. The administration has cut more than $200 million in bilateral aid to the West Bank and Gaza.

In spite of this one-sided approach, Trump has promised that he will resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He has assembled a team led by his son in law, real estate developer Jared Kushner, and the lawyer Jason Greenblatt, a longtime Trump Organization employee. Even though Kushner and Greenblatt have released no details for the forthcoming initiative, it will be dead on arrival. According to reports, key regional players such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan have rejected fundamental components of the plan. After the transfer of the embassy to Jerusalem, Palestinian National Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has refused to meet Kushner and Greenblatt, let alone discuss the possibility of a settlement. Even the Israelis are unlikely to accept the type of plan – including the two-state framework and a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem – that has any prospect of success.

Egypt and Turkey

Relations with two crucial allies in the region, Egypt and Turkey, have been strained in recent years, due in part to growing authoritarianism in both states. Trump’s affinity for other strongmen would seem to hold out the promise of good working relationships, but that has only been the case when it comes to Egypt.

Ever since the 1979 peace agreement with Israel, the Arab Republic has benefitted from $1.3 billion in annual military aid, largely because Washington is eager to keep relations between these key allies on a strong footing. However, in the wake of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s 2014 seizure of power, Egypt’s crackdown on dissent has been an irritant. The Obama administration briefly froze some military aid after the coup, but relented in 2015. Concerned by continued human rights violations and, more importantly, by Cairo’s facilitation of North Korean arm sales, the Trump administration also temporarily withheld some funding – almost $300 million – but released much of it in July 2018.

Initially, Trump and Turkish President Recep Erdoğan enjoyed strong chemistry. Ankara’s illiberal turn, and tension over Turkey’s purchase of Russian arms, its attacks in Syria on Kurdish fighters – a key US ally – and Washington’s refusal to extradite Fethullah Gülen – a cleric accused of involvement in the 2016 coup attempt against the government – had no apparent impact on the relationship between the two men. In fact, according to reports, Trump fist-bumped the Turkish leader during the NATO meeting in Helsinki in July 2018, praising him for not allowing democratic niceties to prevent decisive action, unlike other European leaders.

While Trump did not object to Erdoğan’s authoritarianism, he drew the line when it came to safeguarding his domestic political interests. Among a group of US citizens incarcerated in Turkey, the administration has focused on Andrew Brunson. The fate of the pastor is of special interest to evangelical Christians – a crucial part of the president’s conservative base – and Vice President Mike Pence often highlights Brunson’s case. The administration expected Brunson’s release in July 2018, per an agreement between Trump and Erdoğan. When Turkey failed to act, Washington imposed sanctions on the ministers of justice and the interior and doubled tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminum imports. Analysts predict that Ankara will eventually retreat, but so far, Erdoğan remains defiant.

Further Reading

Miller, Aaron David and Sokolsky, Richard. “What is Trump Getting for Sucking Up to Saudi Arabia?” Politico, August 29, 2018.

Katulis, Brian and Benaim, Daniel. “Trump’s Middle East Policy: The Good(ish), the Bad, and the Ugly.” The New Republic, January 19, 2018.

Lynch, Marc. “Obama and the Middle East: Rightsizing the U.S. Role.” Foreign Affairs 94, no. 5 (September/October 2015): 18 – 27.

Mohseni, Payam and Nakhjavani, Ammar. “The United States Cannot Afford to Pick a Side in the Shia-Sunni Fight.” The National Interest, June 25, 2018.

Nasr, Vali. “Iran Among the Ruins: Tehran’s Advantage in a Turbulent Middle East.” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 2 (March/April 2018): 108 – 118.

Singh, Michael. “Is Washington too focused on Iran’s Nuclear Program?” Foreign Affairs, May 9, 2018.

Syria, Iraq, and the Islamic State

Trump’s feud with Erdoğan comes at an inopportune moment. Turkey is an influential actor in Syria and the US military uses Incirlik Air Base for airstrikes against the Islamic State. In addition, the administration has struggled to formulate a coherent strategy regarding the Syrian civil war. In early 2018, former Secretary of State Tillerson announced a plan that entailed indefinitely committing troops to Syria in order to counter Iran and secure the ouster of President Bashar al-Assad. Then, in April 2018, Trump ordered the military to begin planning for the withdrawal of troops – there are approximately 2200, mainly in eastern Syria – and urged regional allies, such as Saudi Arabia, to assume the costs of reconstructing the parts of the country that have been liberated from the Islamic State. Trump and National Security Adviser Bolton planned to rely on Russia, rather than the presence of US forces, to persuade Tehran to depart.

Recently, James Jeffrey, the State Department’s new “representative for Syria engagement,” announced another reboot. According to the former diplomat, US troops will remain as long as necessary. Trump and his advisers have decided to “find ways to achieve our goals” – which will once again focus on blunting Iran’s influence and fostering a stable government acceptable to Syrians and the international community – “that are less reliant on the goodwill of the Russians.” Washington will not insist on Assad’s departure – according to Jeffrey he has “no future” but it is not “the job” of the United States to oust him – but it has warned that there will be significant consequences if Assad uses chemical weapons again or if Syrian and Russian forces kill large numbers of civilians.

Though Trump repeatedly criticized Obama’s Syrian policy before taking office, as president, he confronts the same challenge as his predecessor – a desire to influence the course of the conflict and the post-war order, without committing large numbers of troops. Like Obama, he has adopted a similar approach, which entails focusing on defeating the Islamic State and pressing other nations to take actions that will serve US interests. He has had little success in these efforts. The continued presence of a small number of US troops will not fundamentally change the dynamic, and, when it comes to determining the nature of Syria’s post-conflict political landscape, it is likely that Washington will have less influence than Russia, Iran, or Turkey.

The United States has more influence in Iraq, but even there, in spite of a massive investment of resources over the last fifteen years, and the continued presence of US troops – 5200, according to the Pentagon – Iran enjoys a stronger position. Popular Mobilization Units – state-approved militias – played a crucial role in defeating Islamic State forces, and the administration fears that many of these units are beholden to Tehran. US officials consider Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, a leading figure in the movement, to be a terrorist, not least because he reportedly has close links to Qassem Soleimani, commander of the Quds Force, the Special Forces unit of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards that operates abroad. Fatah, the political alliance that represents the militias, took second place in the May 2018 parliamentary elections.

Conclusion

Trump apparently supports the ascendancy of a Saudi-Israeli-UAE axis and the corresponding geopolitical consequences. However, there is no indication that this is the product of careful consideration. The administration’s lone public presentation of its vision for the region, the National Security Strategy, merely mentions vague goals such as promoting stability and a favorable balance of power, and, as other analysts have noted, it bears little relation to the president’s other foreign policy pronouncements.

Instead, his decision-making represents the confluence of a number of largely independent factors. Washington has longstanding alliances with Saudi Arabia and Israel, and doubling down on them is easier than following the trail blazed by Obama, which entailed a complicated balancing act of seeking improved, but still tense, ties with Tehran and accepting less cordial relations with the Saudis and Israelis – an arrangement which satisfied few. It also allowed Trump to visit Riyadh and Jerusalem in triumphant style, and gave his hosts the opportunity to take advantage of the president’s well-known susceptibility to flattery.

Furthermore, siding with the Saudi-Israeli-UAE bloc pleases the president’s political base. It overturns key aspects of his predecessor’s legacy – a personal obsession that also plays well with conservatives – and prioritizes the concerns of evangelical Christians regarding Iran and Israel.

Trump’s leadership style has also played a pivotal role in shaping his Middle East policy. By nature, he governs reactively and instinctively and ignores issues he finds uninteresting. His tendency to prioritize loyalty over competence has led to the sidelining of relative moderates and empowered advisers such as Bolton, who has reinforced the president’s belligerent instincts when it comes to Iran, and steered him toward more hawkish positions on Syria.

Perhaps the biggest concern is that the president and his advisers have given little thought to the implications of their decisions. What will be the consequences of abandoning support for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? What will happen if the JCPOA implodes and Iran resumes its nuclear weapons program? What if US influence in Iraq continues to ebb and that of Iran grows? Will new security commitments, in the form of the Middle East Strategic Alliance and the plan to indefinitely station troops in Syria, lead to involvement in other regional conflicts? No one knows the answers to these pressing questions, least of all Trump.

Recent issues of the CSS Analyses in Security Policy series

About the Author

Dr Jack Thompson is Team Head of the Global Security at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. He is, amongst others, the author of Trump and the Future of US Grand Strategy (2017).

No comments:

Post a Comment