PERHAPS nowhere in Europe was John McCain mourned more deeply than in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. He had been one of a small group of American senators who in the 1990s called for NATO to encompass the Baltic states after four decades of Soviet rule. “He was always ready to listen to us and relate our problems and challenges to the US administration, Republican or Democrat,” says Juri Luik, Estonia’s defence minister. “He understood the role of NATO enlargement as part of the reunification of Europe; not everyone in Washington shared that.” Mr Luik has called for NATO’s new headquarters in Brussels to bear his name. Intentionally or not, such tributes also read like rebukes to President Donald Trump, whose commitment to transatlantic security remains as hazy as McCain’s was crystal-clear.

PERHAPS nowhere in Europe was John McCain mourned more deeply than in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. He had been one of a small group of American senators who in the 1990s called for NATO to encompass the Baltic states after four decades of Soviet rule. “He was always ready to listen to us and relate our problems and challenges to the US administration, Republican or Democrat,” says Juri Luik, Estonia’s defence minister. “He understood the role of NATO enlargement as part of the reunification of Europe; not everyone in Washington shared that.” Mr Luik has called for NATO’s new headquarters in Brussels to bear his name. Intentionally or not, such tributes also read like rebukes to President Donald Trump, whose commitment to transatlantic security remains as hazy as McCain’s was crystal-clear.

Baltic pro-Americanism is deep-rooted and intimately linked to the three states’ quest for freedom from Russia. Karlis Ulmanis spent years in exile in Nebraska before returning to Latvia, helping to wrangle its independence and becoming its first prime minister in 1918. He modelled his populist political style on William Jennings Bryan and imported American cultural institutions like 4-H agricultural youth groups and state fairs, even orchestrating aeroplane fly-pasts based on one by the Wright brothers. Opposition to Soviet rule in the 1970s and 1980s collected around, among other icons, Pits Andersons, a rock musician who took the name “Pete Andersen”, drove around Riga in a pink Cadillac and became known as the Latvian Buddy Holly.

Get our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

It was America’s support after the cold war that sealed Baltic affections. The countries emerged from behind the iron curtain after decades of trauma. One survey in 1993 found that more than 40% of citizens had relatives who had been killed, imprisoned or deported by the Nazis, Soviets or both. It was Bill Clinton, urged on by McCain, who put them on the path to NATO membership, and Madeleine Albright who encouraged Latvia to naturalise its ethnic Russians to avoid future conflict. Then it was George W. Bush who presided over the Balts’ arrival in NATO (visiting several times) and Barack Obama who, weeks after Russia’s incursion into eastern Ukraine, visited Estonia to reassure Balts who feared they would be the next target of Russia’s hybrid warfare.

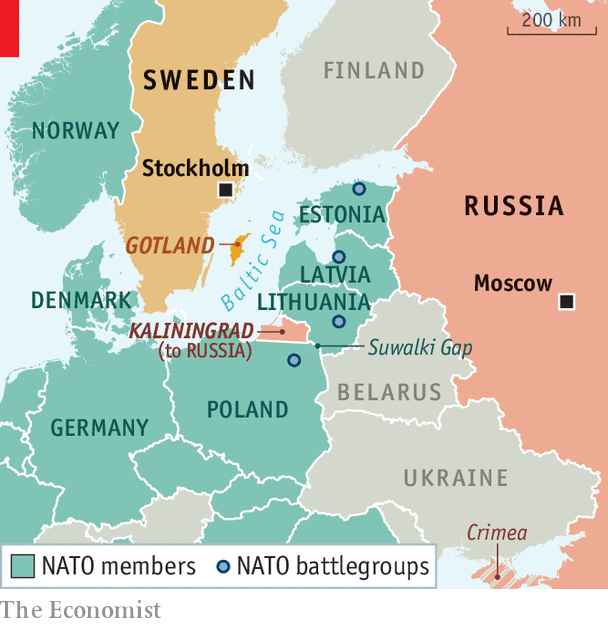

Mr Trump’s election caused anxiety. The president openly admires Vladimir Putin, has questioned America’s NATO spending and had at times appeared reluctant to affirm the alliance’s Article 5, under which an attack on one member is considered an attack on all. His presidency seems to have emboldened Russia. In February it deployed nuclear-capable Iskander missiles to Kaliningrad, its militarised enclave between Poland and Lithuania, and in September carried out its largest-ever post-Soviet military exercise, a 300,000-soldier simulation of a major land war. “Every time Trump criticises NATO, people in the Baltics get very worried,” says Nils Muiznieks, a Latvian-American political scientist. Baltic elites are somewhat reassured by enduring support for NATO in Congress and by Mr Trump’s emollience on a visit of Baltic presidents to Washington in April. Raimonds Bergmanis, Latvia’s defence minister, was in the room: “The president was very clear about his commitments to our security.” But his inconsistency continues to worry the Balts. (A threat this week by America’s NATO ambassador to “take out” the missiles is not exactly reassuring.)

A second concern also haunts the Baltic capitals. At a time when America’s commitment to Europe is in question, Europe’s commitment to America and to a common security architecture could be fracturing in response. In Berlin, Brussels and Paris it is becoming voguish to advocate “post-Atlanticist” foreign and defence policies making Europe more independent from America. “The US can no longer and will no longer be the stabiliser and protector of Europe,” wrote a group of continental intellectuals in Die Zeit, a liberal German weekly, last October. Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel, Atlanticists by their countries’ standards, have not endorsed such arguments. But even they have said that Europe can no longer rely on America.

Mind the Suwalki Gap

What seems expansive and defiant in comfortable foreign-policy salons in Europe’s west is, to Baltic leaders, not just fanciful but irresponsible. In a city like Riga, Russia is close, immediate and scary. It has a record of bullying the Baltic states. Estonians recall the crippling Russian cyber-attack that brought their country to a standstill in 2007. Military planes routinely fly into Baltic air space from neighbouring Kaliningrad and St Petersburg, and Russian television pumps inflammatory disinformation into societies with large ethnic Russian minorities. Officials here lie awake at night worrying about the Suwalki Gap, the 65km Lithuanian-Polish border strip between Kaliningrad and Russian-allied Belarus that is the Balts’ only land link to the rest of Europe and could be cut off fast if Russia doubted NATO’s willingness to defend its members. No surprise, then, that in Mr Muiznieks’s words: “Talk of strategic autonomy scares the hell out of us.”

Baltic leaders raise practical objections to the notion; Europe lacks the cash, but it also lacks the willingness to create a real substitute for America’s security umbrella. The EU’s existing battle-groups, part of its tentative shuffle towards a military capacity of its own, have remained in their barracks as politicians have argued about where and how they should be deployed. Anything like strategic autonomy would take decades of “post-Atlanticist” investment and political evolution.

To the Balts, that is a long time. This year they are celebrating the 100th anniversary of their independence. It is a time of happiness and national pride, but also a reminder that these countries are young, vulnerable and pressed up against a large, threatening neighbour. McCain understood that. Balts wish more of their European partners did so, too.This article appeared in the Europe section of the print edition under the headline "In Europe’s McCainland"

No comments:

Post a Comment