By SEAMUS DANIELS

The Trump Administration’s 2018 National Defense Strategy was remarkable for its candor in identifying China and Russia as America’s chief “strategic competitors.” But unlike earlier, relatively anodyne strategy documents from the Obama Administration, the 2018 strategy didn’t specify the forces required, let alone how much they might cost — at least, not in the unclassified summary released to the public. In this commentary, part of our continuing collaboration with the Center for Strategic & International Studies and its FY 2018 Endgame Series, CSIS scholar Seamus Daniels looks at what questions the strategy leaves unanswered.

The Trump Administration’s 2018 National Defense Strategy was remarkable for its candor in identifying China and Russia as America’s chief “strategic competitors.” But unlike earlier, relatively anodyne strategy documents from the Obama Administration, the 2018 strategy didn’t specify the forces required, let alone how much they might cost — at least, not in the unclassified summary released to the public. In this commentary, part of our continuing collaboration with the Center for Strategic & International Studies and its FY 2018 Endgame Series, CSIS scholar Seamus Daniels looks at what questions the strategy leaves unanswered.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), released by the Pentagon last January, redefined the geopolitical challenges facing the United States and recognized the “reemergence of long-term, strategic competition” with China and Russia as the greatest priority for the Department of Defense (DoD).

The strategy document issues a dire warning that the United States’ comparative military advantage over its adversaries has “eroded,” and that in order to reverse this trend and check the ambitions of its competitors, the country “must invest in modernization of key capabilities through sustained, predictable budgets.” The document’s emphasis on modernization underpins one of its primary goals: creating a more lethal force characterized by enhanced readiness, innovative operational concepts, and agile force posture and employment.

While the NDS calls for a “more resource-sustainable approach” to fund this modernization effort, the unclassified summary of the strategy fails to delineate how it plans to fund its ambitions. Previous strategy documents provided guidance for approaching the associated costs of a particular strategy or noted the tradeoffs of prioritizing some areas over others. For example, both the 2010 and 2014Quadrennial Defense Reviews (QDR) included projections for future military force structure. Notably, both documents also indicated the tradeoffs their strategies assumed. The 2014 QDR, in particular, explained the steps DoD would be forced to take if the 2011 Budget Control Act spending caps were not raised or eliminated.

Russia’s new T-14 Armata tank on parade in Moscow.

The unclassified summary of the NDS, on the other hand, merely states that the strategy “underpins our planned fiscal year 2019-2023 budgets, accelerating our modernization programs and devoting additional resources in a sustained effort to solidify our competitive advantage.” This does not explain where or how DoD plans to procure the resources necessary to fully fund DoD’s projected “modernization bow wave.”

More worryingly, however, is the strategy’s emphasis on rebuilding readiness in addition to modernization while the Trump administration has simultaneously requested increases in force structure across the Services. As Kathleen Hicks noted in her “Defense Strategy and the Iron Triangle of Painful Tradeoffs,” DoD is forced to strike a balance between capability (modernization), capacity (force structure), and readiness. Yet the administration has chosen to increase all three legs of the triangle without explaining how it plans to foot the bill.

Some might point to the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018) as a solution to this fiscal challenge. Passed in February, BBA 2018 raised the budget caps for discretionary defense spending in FY 2018 and FY 2019 by $80 billion and $85 billion, respectively – significantly greater increases than the budget deals agreed to in 2013 and 2015. The legislation ensures that total national defense spending for the upcoming fiscal year will be set at $716 billion, a 13 percent real increase above FY 2017 funding levels.

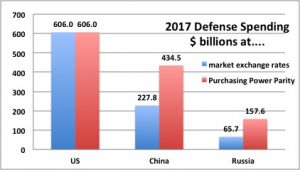

SOURCE: DoD 2019 budget submission, SIPRI database

However, to better understand how the administration intends to fund the modernization plan outlined in the NDS, one must assess DoD’s five-year spending projections known as the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). As Todd Harrison and I note in our recent analysis, DoD projects limited growth in its base budget over the course of the FYDP, just 1.2 percent total growth above inflation from FY 2019 to FY 2023. Acquisition funding in the base budget, including RDT&E and procurement, is expected to fall by 2 percent over the same period, prompting further questions of how DoD plans to fund its modernization plans.

Significant changes to DoD’s budgetary projections seem unlikely given comments from administration officials. A major boost appears even less likely if Democrats take the House in November’s midterm elections, according to statements made by current HASC ranking member Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA).

While the Trump administration’s defense budget projections do not show significant real growth in the budget over the coming years, defense officials have touted efficiency reforms as a potential source of savings that can be reinvested elsewhere in the department to fund modernization priorities. DoD’s first-ever Chief Management Officer, Jay Gibson, projected that the department would save $6 billion in FY 2019 and $46 billion over the course of the FYDP by eliminating waste and adopting more efficient business practices.

Prior analysis, however, has shown that generating significant savings through efficiency reforms is notoriously difficult, and DoD must be realistic in its approach to making these reforms by not spending the savings before they are realized.

Patrick Shanahan

Recent statements and actions from within the department suggest that the leadership has recognized that major savings from reform are unlikely. A recent memo from Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan noted savings from IT and logistics reforms generated approximately $300 million in savings in FY 2018 while Defense Health Agency consolidation efforts are expected to save more than $2 billion annually by 2023 – numbers far short of the $46 billion projected over the FYDP. Gibson meanwhile is reportedly being removed from his position as CMO due to his “lack of performance.”

However, recent comments from Shanahan indicate an understanding that tradeoffs must be made to fund modernization efforts. At the 2018 Air Force Association Conference, the deputy secretary explained that “now is the time to make choices about what we will and what we won’t do. Those choices as reflected in [the FY 2020] budget will determine what our military looks like for the next fifty years.” However, we will have to wait until the FY 2020 “masterpiece” budget is released to understand if the administration is really willing to make the difficult, yet necessary decisions to achieve the modernization goals outlined in the NDS.

No comments:

Post a Comment