LT GEN H S PANAG

India must not forget the catastrophic defeat of 1962 war with China, when our Army was routed in just 10 days of actual battle in two phases of five days each in October and November. The whole of North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and 50 per cent of Ladakh were shamefully abandoned. To add insult to the injury, after achieving its political and military aims, China unilaterally declared a ceasefire and withdrew.

India must not forget the catastrophic defeat of 1962 war with China, when our Army was routed in just 10 days of actual battle in two phases of five days each in October and November. The whole of North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and 50 per cent of Ladakh were shamefully abandoned. To add insult to the injury, after achieving its political and military aims, China unilaterally declared a ceasefire and withdrew.

So complete was our defeat that for the next 24 years, we did not dare to deploy our Army on the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Not until the mercurial General K. Sundarji forced the issue after the Sumdorong Chu incident in 1986.

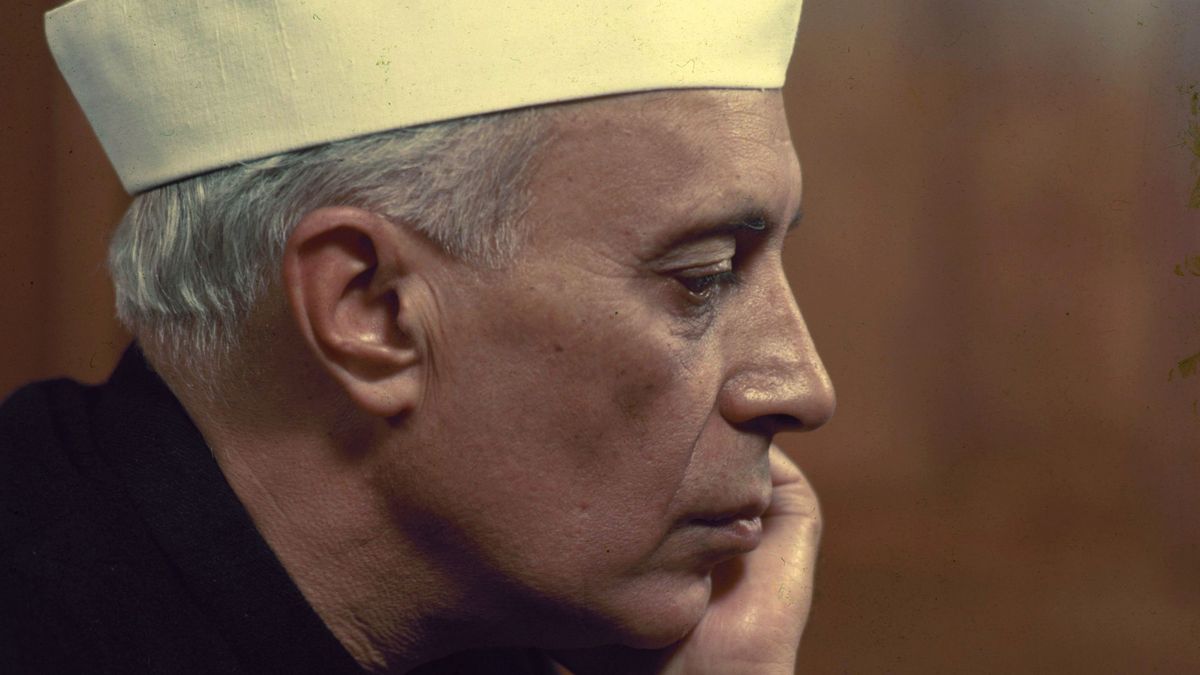

The responsibility for this Himalayan debacle rests squarely with former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Most historians and military analysts blame him for not creating the military capability and border infrastructure necessary to ensure our territorial integrity and prepare for the threat posed by China.

Given the abject poverty of India, there was no way Nehru could have created the military capability to counter the seasoned PLA, armed with the best Russian weaponry. It had demonstrated its capability by imposing a stunning defeat on the US in Korea. The only option was to become a subservient ally of the US to get the desired military aid and let the guns take priority over bread.

India decided not to do so due to the collective idealism of Nehru and our political leaders, all of whom had taken part in the freedom struggle. And, also because our strategic assessment was that despite the territorial dispute, the probability of war was very low. Moreover, poverty alleviation was a national goal.

Even 56 years after 1962, our border infrastructure is still 30 per cent of what China has created and well short of even what we ourselves desire, and our military can barely keep its head above the water against the PLA. To expect Nehru to have done it with far fewer sources is unrealistic.

‘Frontier’, ‘border’ and ‘international boundary’ are geostrategic terms used to describe the in-between space between contiguous nation states in ascending order of legitimacy and international acceptance.

What we inherited in the upper Himalayas was a frontier region shaped by the Himalayan chapter of the Great Game. Imperial Britain used the dysfunctional Tibet as a buffer state after subjugating it militarily in 1903-04, and thereafter maintained a token military presence at Yatung and Gyantse primarily to safeguard the trade route.

The frontier region was not physically occupied. In the eastern sector, the boundary was demarcated by the McMahon Line under a tripartite agreement between British India, Tibet and China. In the western sector, the reliance was placed on the 1842 Sikh/Dogra Empire-Tibet treaty.

However, the boundary of the Aksai Chin area along the Kunlun Mountains was shown as un-demarcated.

Conventions and treaties are given short shrift by nation states in the frontier regions where physical, political and military control decides the eventual delimitation of an international boundary. This was the backdrop when the Sino-Indian frontier dispute began in the early 1950s.

Once China occupied Xinjiang and Tibet and made its preliminary territorial claims, Nehru evolved a strategy to deal with the situation. Our military was weak and we did not have any border infrastructure. The military was virtually impotent with respect to the northern borders. Consequently, the strategy adopted was to rely on diplomacy and avoid conflict. Simultaneously, it was decided that using the traditional doctrine of Forward Policy, our ‘flag’ must be planted in the frontier regions at the earliest to be in a better negotiating position for a final settlement. China began a similar exercise on the southern borders of Tibet.

In NEFA, India pre-empted China and secured the areas up to the McMahon Line by 1951 using the Assam Rifles. This was a remarkable feat because until then Tibet exercised virtual control over Tawang and parts of Lohit division. In the western sector, China pre-empted us and secured a major part of Aksai Chin and built a road through it linking Xinjiang to Tibet. However, elsewhere, we managed to plant our ‘flag’ using the CRPF and the Intelligence Bureau (IB).

By mid-1959, we had reached little beyond the present day LAC in the western sector and the McMahon Line in the eastern sector, and our police/paramilitary came face to face with the Chinese border guards. Due to the revolt in Tibet and India granting asylum to the Dalai Lama in March 1959, China hardened its position and came out with a new claim line in Ladakh. Nehru had to then decide whether to accept the actual ground positions as a mutually acceptable border without giving up our claims for a final settlement or to continue with the brinkmanship on the premise that war will not take place. He chose the latter option.

The first two clashes took place on 25 August at Longju in Lohit Division and on 21 October at Kongka La in Ladakh. Until now, the goings-on in the frontier regions had been secretive and were not in the public domain. However, the border clashes and casualties led to immense Parliament and public pressure. Nehru lost his nerve and abandoned a fairly successful strategy despite China offering a status quo settlement. All his subsequent actions were panic-driven and tactical, bereft of strategic thought. NEFA and Ladakh were placed under the Army control in August and December 1959 respectively.

Diplomacy was abandoned. The pragmatic frontier- flagging ‘Forward Policy’ adopted so far was replaced by a more aggressive ‘Forward Policy’, which actually became ‘forward movement of troops’, to call the Chinese bluff. Less by design and more by default, Nehru blundered into a military confrontation on an unfavourable terrain and with an army that was ill-prepared for the task. Rather than calling the bluff of the Chinese, our own bluff was called.

The author served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC in C Northern Command and Central Command. Post retirement, he was Member of Armed Forces Tribunal.

No comments:

Post a Comment