LT GEN H S PANAG

The politico-strategic aim of the war was to ‘teach India a lesson’, and prevent it from challenging the Chinese borders and sovereignty over Tibet. War is not an act of senseless passion, but is controlled by political objective,” said military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. Chinese maps had started showing Aksai Chin and the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) as part of China in the early 1950s. In 1954, India also issued new maps to show our boundary along the Kunlun Mountains in Ladakh and the McMahon Line in the east. Both sides began to ‘flag’ the frontier region as per their claims, with the Chinese preempting us in Aksai Chin, and India preempting them in NEFA.

The politico-strategic aim of the war was to ‘teach India a lesson’, and prevent it from challenging the Chinese borders and sovereignty over Tibet. War is not an act of senseless passion, but is controlled by political objective,” said military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. Chinese maps had started showing Aksai Chin and the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) as part of China in the early 1950s. In 1954, India also issued new maps to show our boundary along the Kunlun Mountains in Ladakh and the McMahon Line in the east. Both sides began to ‘flag’ the frontier region as per their claims, with the Chinese preempting us in Aksai Chin, and India preempting them in NEFA.

In 1959, Zhou Enlai had clearly stated that the entire boundary was under dispute and had never been delimited. He subtly proposed that status quo should be maintained until final resolution. This implied a trade-off between Aksai Chin and acceptance of the McMahon line in the Northeast as the boundary. This proposal was rejected by India, which insisted that the Chinese must withdraw from Aksai Chin before negotiations could begin. Until now, the Chinese had shown no inclination to use force, though given the favourable terrain and their military capability, they were in a position to do so.

What then led to the war? What were the political and military aims of China? To say that the border dispute and India’s aggressive “frontier flagging” policy – “forward movement” of troops after 1959 – was the primary cause of the war would be rewriting the theory of war.

Wars imply severe economic and human cost, and hence are the instrument of last resort. The ultimate political objective of war is to impose peace on one’s own terms. To achieve this, one has to compel the opponent to submit to one’s will. Apart from diplomacy and economic coercion, ultimately, the will of the enemy is broken by imposing a military defeat. Military aims thus flow out from political aims, and are not an end unto themselves.

While the boundary dispute was the immediate casus belli in 1962, the fundamental causes are rooted in the competitive conflict for relative position of preeminence in Asia and the world, and the Indian threat to the Chinese vulnerability in Tibet.

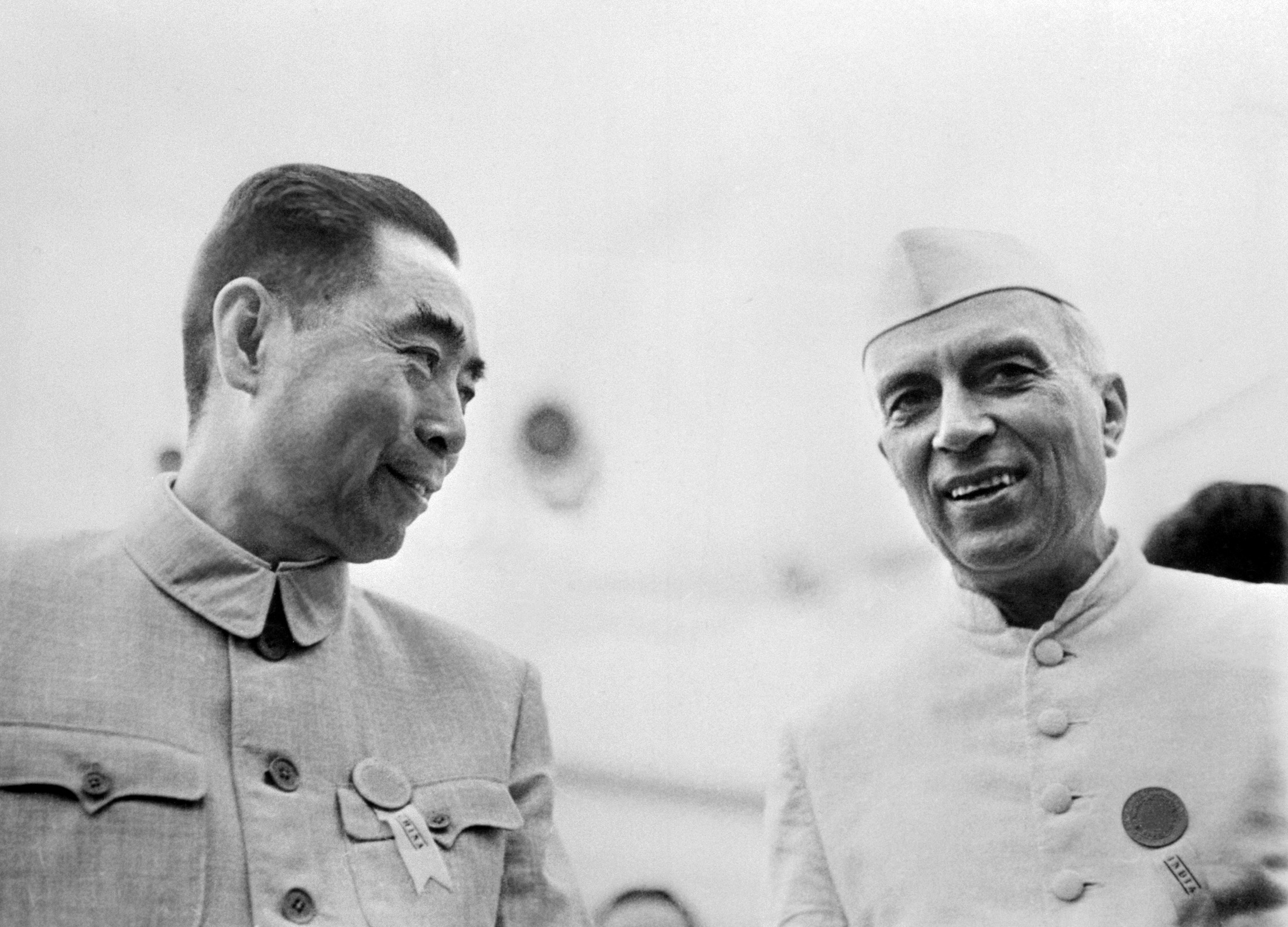

From the very onset, China had let the world know that it is ordained to be a great power. India was seen as a rival power centre and the international personality of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was an anathema to the Chinese leadership. Thus, there was an undeclared aim to cut Nehru down to size and neutralise India as rival.

Tibet is China’s Achilles heel. Tibet is a civilisation by itself and had never accepted the sovereignty of China. At that time, China believed India was assisting the insurrection in Tibet in conjunction with the CIA to restore status quo ante pre-1950. The asylum to the Dalai Lama in March 1959 confirmed this Chinese belief. The road through Aksai Chin was essential for China to maintain its control over Tibet. Thus, India’s rejection of a reasonable Chinese proposal to exchange Aksai Chin for acceptance of the McMahon Line was seen as part of India’s designs in Tibet.

Over the next three years, India aggressively pursued the forward policy to establish its writ over the territory it considered legitimately belonging to it. China responded in a quid pro quo manner with its policy of “peaceful coexistence”, but continued to exercise restraint to avoid precipitating the situation. India was further emboldened, and its belief that China would not go to war while it secured its legitimate territory was further reinforced.

The Galwan River and Dhola Post incidents convinced the Chinese that war was inevitable.

Chinese leadership was well-versed in the art of war and was intimately involved with the decision-making and had deliberated its strategy over a series of meetings. By early October, it gave formal directions to the PLA to execute the plans for the war.

The politico-strategic aim of the war was to “teach India a lesson”, neutralise it as a rival for position of preeminence in Asia and the world, and prevent it from challenging the Chinese borders and sovereignty over Tibet.

The military objective was to impose an absolute defeat on Indian forces operating in NEFA and Ladakh, and in so doing, completely annihilate the forces in NEFA, seize territory up to the plains (in NEFA) and the 1959 claim line in Ladakh.

The difference in the approach between Ladakh and NEFA was due to the logistics problems faced by the PLA in Ladakh, and the destruction of only one brigade that India deployed was not considered a worthwhile objective. Moreover, China had already secured the territory it had claimed.

The ideal time for the campaign in the high-altitude areas of Ladakh and NEFA is from June to October. Due to the initial policy of restraint followed until the Dhola incident, the decision-making for the war had got delayed and the final decision was taken only in the first week of October. This effectively gave the PLA only one month to achieve its military objectives. This delay also led China to unilaterally withdraw upon completion of the annihilation and achievement of other objectives.

It would have been extremely difficult to maintain the PLA forces via the snowbound passes over very poor motorable tracks. The forces would also have been vulnerable to counter attack in the lower reaches.

China did not want the USA to physically intervene to assist India. Also, the Chinese claims in NEFA were merely a ploy to justify the seizure of Aksai Chin. The compulsion forced by weather conditions was eventually used to enhance China’s prestige in the world.

The politico-strategic aims evolved by a political leadership with an experience of 30 years of continuous war were achieved in totality by an equally experienced and battle-hardened PLA through a clinically-conducted war that lasted one month. A classic example of how a nation must exercise force in pursuit of its national interests.

The author served in the Indian Army for 40 years. He was GOC-in-C Northern Command and Central Command. Post-retirement, he was a member of the Armed Forces Tribunal.

No comments:

Post a Comment