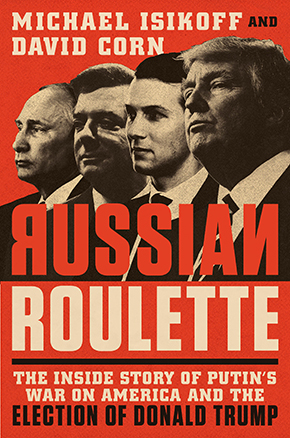

This is the second of two excerpts adapted from Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump (Twelve Books), by Michael Isikoff, chief investigative correspondent for Yahoo News, and David Corn, Washington bureau chief of Mother Jones. The book will be released on March 13. CIA Director John Brennan was angry. On August 4, 2016, he was on the phone with Alexander Bortnikov, the head of Russia’s FSB, the security service that succeeded the KGB. It was one of the regularly scheduled calls between the two men, with the main subject once more the horrific civil war in Syria. By this point, Brennan had had it with the Russian spy chief. For the past few years, Brennan’s pleas for help in defusing the Syrian crisis had gone nowhere. And after they finished discussing Syria—again with no progress—Brennan addressed two other issues, not on the official agenda.

First, Brennan raised Russia’s harassment of US diplomats—an especially sensitive matter at Langley after an undercover CIA officer had been beaten outside the US embassy in Moscow two months earlier. The continuing mistreatment of US diplomats, Brennan told Bortnikov, was “irresponsible, reckless, intolerable and needed to stop.” And, he pointedly noted, it was Bortnikov’s own FSB “that has been most responsible for this outrageous behavior.”

Then Brennan turned to an even more sensitive issue: Russia’s interference in the American election. Brennan now was aware that at least a year earlier Russian hackers had begun their cyberattack on the Democratic National Committee. We know you’re doing this, Brennan said to the Russian. He pointed out that Americans would be enraged to find out Moscow was seeking to subvert the election and that such an operation could backfire. Brennan warned Bortnikov that if Russia continued this information warfare, there would be a price to pay. He did not specify the consequences.

Bortnikov, as Brennan expected, denied Russia was doing anything to influence the election. This was, he groused, Washington yet again scapegoating Moscow. Brennan repeated his warning. Once more Bortnikov claimed there was no Russian meddling. But, he added, he would inform Russian President Vladimir Putin of Brennan’s comments.

This was the first of several warnings that the Obama administration would send to Moscow. But the question of how forcefully to respond would soon divide the White House staff, pitting the National Security Council’s top analysts for Russia and cyber issues against senior policymakers within the administration. It was a debate that would culminate that summer with a dramatic directive from President Barack Obama’s national security adviser to the NSC staffers developing aggressive proposals to strike back against the Russians: “Stand down.”

At the end of July—not long after WikiLeaks had dumped more than 20,000 stolen DNC emails before the Democrats’ convention—it had become obvious to Brennan that the Russians were mounting an aggressive and wide-ranging effort to interfere in the election. He was also seeing intelligence about contacts and interactions between Russian officials and Americans involved in the Trump campaign. By now, several European intelligence services had reported to the CIA that Russian operatives were reaching out to people within Trump’s circle. And the Australian government had reported to US officials that its top diplomat in the United Kingdom had months earlier been privately told by Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos that Russia had “dirt” on Hillary Clinton. By July 31, the FBI had formally opened a counterintelligence investigation into the Trump’s campaigns ties to Russians, with subinquiries targeting four individuals: Paul Manafort, the campaign chairman, Michael Flynn, the former Defense Intelligence Agency chief who had led the crowd at the Republican convention in chants of “Lock her up!”, Carter Page, a foreign policy adviser who had just given a speech in Moscow, and Papadopoulos.

One senior US government official briefed on the meeting was told the president said to Putin in effect, “You fuck with us over the election and we’ll crash your economy.”

Brennan spoke with FBI Director James Comey and Admiral Mike Rogers, the head of the NSA, and asked them to dispatch to the CIA their experts to form a working group at Langley that would review the intelligence and figure out the full scope and nature of the Russian operation. Brennan was thinking about the lessons of the 9/11 attack. Al Qaeda had been able to pull off that operation partly because US intelligence agencies—several of which had collected bits of intelligence regarding the plotters before the attack—had not shared the material within the intelligence community. Brennan wanted a process in which NSA, FBI, and CIA experts could freely share with each other the information each agency had on the Russian operation—even the most sensitive information that tended not to be disseminated throughout the full intelligence community.

No comments:

Post a Comment