EVERY month the Longyue Foundation, a Chinese charity based in the southern city of Shenzhen, pays modest stipends to nearly 3,000 extremely elderly veterans of China’s war with Japan. In its early years the foundation got most of its money from a handful of supportive businesspeople, explains Luo Yangwei, one of its bosses. That changed in 2014 when it began soliciting donations online. Last year it collected about 46m yuan ($6.7m) from warm-hearted internet users, whose numerous small gifts amounted to almost nine-tenths of what it raised. This year it hopes to boost its total income by 10%.

EVERY month the Longyue Foundation, a Chinese charity based in the southern city of Shenzhen, pays modest stipends to nearly 3,000 extremely elderly veterans of China’s war with Japan. In its early years the foundation got most of its money from a handful of supportive businesspeople, explains Luo Yangwei, one of its bosses. That changed in 2014 when it began soliciting donations online. Last year it collected about 46m yuan ($6.7m) from warm-hearted internet users, whose numerous small gifts amounted to almost nine-tenths of what it raised. This year it hopes to boost its total income by 10%.

Longyue is one of many charities hoping to benefit from an online fund-raiser run annually by Tencent, a tech giant, which ends on September 9th. During last year’s edition of the “99 Charity Day”, users of its WeChat messaging app gave 830m yuan to good causes (about as much as is raised biennially by “Red Nose Day”, a long-running British telethon). Tencent and its partners gave matching donations that brought the total to 1.3bn yuan.

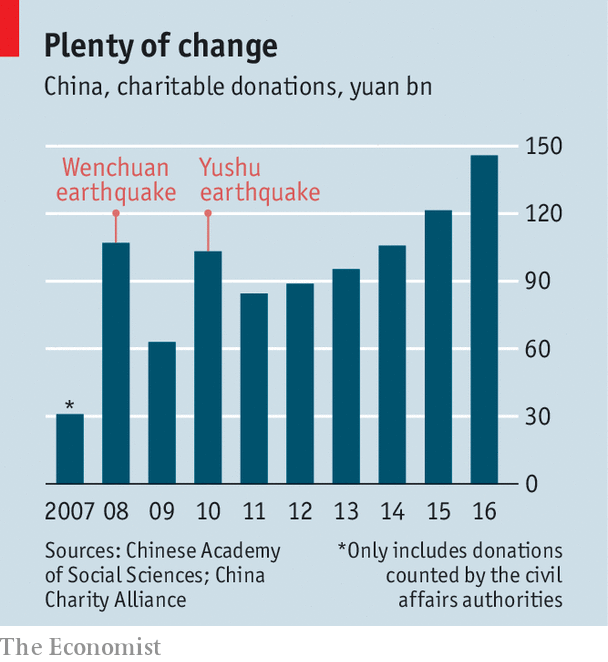

Although annual charitable giving is growing fast in China—up by about two-thirds since 2011—it still looks meagre when compared with donations in other countries. In 2016 Chinese gave away sums equivalent to about 0.2% of their country’s GDP, whereas Americans donated more than 2%. Last year the Charities Aid Foundation, a British NGO that every year ranks 140 or so countries according to the proportion of their people who say they give time, money or assistance to strangers, placed China second from bottom (Yemen was last on the list).

Differing definitions of charity may partly explain this. Much Chinese giving goes on within personal networks, not in the public sphere. People often open their wallets to help out their “cousin’s wife’s paternal grandpa” without necessarily considering it a charitable gift, says Holly Snape of Peking University. Donations to organisations the Communist Party feels uneasy about, such as religious groups, are underreported too. But low levels of recorded giving are also a historical legacy. During Mao’s rule the party abhorred charity. It did not want do-gooding groups to show up the state’s failings. People were told that the party was their only saviour.

Mao-era shackles were relaxed during the 1980s, when the party began allowing big state-backed charities to operate. For smaller, independent ones a watershed moment came in 2008, when a devastating earthquake struck Wenchuan in the south-western province of Sichuan. Their assistance in relief efforts impressed officials and ordinary Chinese. The catastrophe resulted in a step-change in charitable giving (see chart).

Most donations are from companies. Among individuals, people in their 20s and 30s appear particularly enthusiastic about giving money to charity. Doing so is made easier for them by mobile payment systems. But red tape and the party’s paranoia continue to inhibit many public-spirited Chinese. Scandals have also undermined public trust in charities. Chinese people quizzed about their giving habits still mention a case that came to light in 2011 of a socialite who enjoyed a lavish lifestyle and appeared to be affiliated to the Chinese Red Cross. (It denies any connection with her.) Meanwhile China’s charitable sector remains short of expertise. Jack Ma of Alibaba, another tech firm, once quipped that it was easier to make money in China than to give it away.

Tackling these problems was at least one motivation for a charity law that was passed in 2016 after several years of drafting. It made registration easier, at least in theory, by junking a requirement that charities find a public agency to sponsor them (persuading risk-averse officials to do so has been a long-standing obstacle for all sorts of grassroots organisations, many of which end up securing legal status only by pretending to be businesses). It also granted more organisations the right to raise funds directly from the public.

The new rules were greeted with optimism by many NGO workers, not least because of the surprisingly collaborative approach authorities took to drafting them. Ms Luo of the Longyue Foundation says the law’s stipulations about fundraising have been a big advantage for her organisation. When rattling the tin Longyue no longer has to work with a government-approved agent, who used to take a cut. Jia Xijin of Tsinghua University says publicity surrounding the law has helped raise officials’ awareness that China’s charities are important to its development.

Yet during the past two years the law’s shortcomings have become more evident. Registered charities have struggled with a requirement that they spend no more than 10% of donations they receive on administration. The aim of this rule is partly to encourage thrift and boost public trust. But officials also want to prevent independent organisations from growing large enough to put pressure on the party.

Officials have been picky about what kinds of organisations get charitable status under the new law. The party is enthusiastic about groups that promise to feed the hungry, heal the sick and clothe the poor—all things which the party says are its priorities, too. But charities that engage in advocacy, such as for gay rights or against sexual harassment, still find it hard to get approval. Previously all manner of unregistered groups had managed to operate in China thanks to vagueness in the rules surrounding charities and other NGOs. But with regulations now clearer about which kinds are permitted, officials are becoming less inclined to turn a blind eye to those that try to operate under the radar. Even as it has shown greater tolerance of charities that suit its purposes, the party has been making life tougher for those that it does not like. At the start of 2017 it greatly increased its oversight of foreign NGOs, which had traditionally supported many of their small Chinese counterparts with funding and expertise. Now foreign groups must gain approval to operate from China’s Ministry of Public Security, which is deeply suspicious of NGOs. The law has made it more difficult for Chinese organisations to receive foreign donations.

And the tightening continues. Draft regulations that were released for public comment in August would increase restrictions on domestic NGOs of all types, fear some charity workers. They would clarify penalties for violators. One worried lawyer says she believes they might result in an attempt by the government to purge Chinese civil society by forcing a large swathe of it to re-register. The party is growing keener for Chinese to open their wallets—or, more likely, their digital ones—but only to charities that please it.

No comments:

Post a Comment