Years ago, the world witnessed the creation of the first major “cyberweapon.” Secretly loaded onto an unknown Iranian worker’s USB flash drive, an American-Israeli line of malicious code now known as Stuxnet entered Iranian computer networks and spread like a cancer. The self-replicating computer worm burrowed itself in 15 Iranian industrial networks, eventually infecting its primary target: Iran’s nuclear facility at Natanz. Workers watched helplessly as centrifuges spun out of control, tricked by the worm to spin faster and faster until its eventual mechanical suicide. By the attack’s end, over 900 centrifuges were left in ruin. Strands of the worm, which found its way into the wild, still infect computers to this day.

Stuxnet, which went through years of development between its initial creation and eventual deployment, required rigorous levels of approval and government oversight before its launch. The weapon was treated as significantly different from conventional weapons and featured an approval process similar to those reserved for nuclear weapons. President Obama himself had to personally authorize the attack. That approval process is changing.

This past month, buried beneath an ant mound of political scandal and news cacophony, President Trump set in motion a plan to gut Presidential Policy Directive 20, an Obama-era policy limiting the use of destructive offensive cyberweapons like Stuxnet. What exactly will replace PPD-20 remains clouded in uncertainty, but one thing seems clear: The military’s gloves are off. Without PPD-20, the U.S. military can now use hacking weapons with far less oversight from the State Department, Commerce Department, and intelligence agencies. A paper released earlier this year by U.S. Cyber Command, the hacking arm of the U.S. military, outlines a proposed policy of increased military intervention, and paints a landscape of nations under constant cyberassault. It’s not a stretch to say the removal of PPD-20 may fundamentally restructure the way America conducts war in cyberspace. Whether or not that is a good thing depends on whom you ask.

“What this is all about is streamlining the process and giving the military permission to use cyberweapons under certain circumstances without having to go through a cumbersome process of coordination with all the different agencies,” former Navy Captain Gail Harris says. In conversation, Harris, who was involved in cyberdefense for the Department of Defense, echoed the arguments laid forth by Cyber Command in its paper. In that document, Cyber Command describes cyberspace as an “active and contested operational space in which superiority is always at risk.” Whether you like it or not, Cyber Command argues, we are currently engaged in a persistent war of code with adversaries continuously attacking and entrenching themselves deep in American networks. The brisk nine-page document details a world under constant subversion. These “persistent threats,” Cyber Command argues, require swift and aggressive military responses in kind. Be they Russian and Iranian state hackers, terrorists, or hacktivists, the document blames bureaucratic red tape and political hand-holding for much of America’s recent cyber woes.

“We cede our freedom of action with lengthy approval processes that delay US responses or set a very high threshold for responding to malicious cyber activity,” the vision statement reads.

If Cyber Command has its way, it will also be able to transition its fundamental role from defense to potentially more offensive campaigns. Cyber Command says it wants to “expand the military options available to national leaders,” and “defend forward as close as possible to the origin of adversary activity.” The move follows a recent trend by officials geared toward strengthening Cyber Command and granting it far more offensive capability.

While anyone losing hair over election hacking, foreign manipulation, and electrical grid vulnerabilities may take some solace in sharpening the military’s cyber teeth, the prospect of a perpetual online war could come with serious, sometimes unforeseen, consequences.

The Plunge Into Perpetual War

“We’ve slipped into permanent warfare,” Columbia research scholar and cybersecurity expert Jason Healey told Select All. “There is no winning this war, it is happening online.” Healey, who wrote the first history of cyberconflict and previously worked on network defense for the Pentagon, said he worried traditional military solutions may simply not work to address cyberconflict. “The military is asking politicians to give them this authority and then get out of the way forever. Once we have done this, we are not going to be able to go back to the way it was before.”

Though agreeing that changes to PPD-20 were needed, Healey said the “friction” between the military and the government over approval processes act as a force for good.

“I like friction,” he said. “Friction is how you avoid bombing Afghan weddings. This interagency process is in place to ensure civilian control over the military, limit potential escalation, and ensure other agencies that might be affected by cyberoperations have a say in the decision.”

In addition to the issues of oversight, another problem arises through the complex nature of just how these digital weapons work. Cyberweapons and hacking tools on the state level differ widely from the air strikes, tanks, and fighter jets of conventional war. Unlike roaring battlegrounds, networks transcend the geographical bounds of nation states. Militaries can, and do, launch attacks from other countries, purposefully muddying attribution attempts. Distinguishing between a hostile enemy and a civilian on their computer bemuses traditional military logic even further. What may begin as a targeted military strike in cyberspace can quickly amplify into a tsunami of code crushing anything in its path.

“At the end of the day, there just might not be a military solution,” Healey said. “Fighting fire with fire sounds great, except we are all standing in dry glass covered in gasoline.”

This is not just theory; we have proof.

Last June, Europe witnessed what happens when a cyberweapon loses control. As a recent Wired story describes in detail how NotPetya, a cyberattack that was intended as a show of political force against Ukraine by the Russian government, quickly hopped borders and dealt over $10 billion in damages around the world. Over 300 Ukrainian companies were hit in what one Ukrainian man described to Wired as “a bombing of all our systems.” Nearly 5,000 miles to the west, Maersk shipping containers were left stranded in New Jersey. The code cared little for international borders.

Others in support of less restrictions, like Richard Harknett argue in favor of the U.S. attacking enemies before they ever reach American networks in the first place. “Previous U.S. approaches ultimately left the U.S. playing ‘clean up on aisle nine,’” Harknett wrote.

In a similar vein, Harris said a U.S. posture of strength could deter adversaries from challenging with attacks in the first place. “I think if people know that we are going to respond under certain circumstances, then I think that will lead to less attacks,” she said. “Right now there are no red lines for our cyberopponents.”

Maybe. It’s certainly true that, at least on the public level, where and when the U.S. will take on enemies with code remains shrouded in secrecy. It also may be true that a show of cyber teeth by the U.S. military could intimidate enemies and send would-be attackers meekly cowering over the prospect of finding themselves on the receiving end of a cyber equivalent to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But another less palatable possibility may exist. A ramping up of aggressive U.S. attacks could, according to Healey, have just the opposite effect, and encourage others to step up and match that escalation with even greater force. Several rounds of this back and forth, and the not long specter of a Cold War era arms race runs the risk of resurrection, this time through lines of code and paid trolls.

In its vision statement, Cyber Command attempted to jump ahead of criticism, and denied claims that it is “militarizing” cyberspace.

Even if it’s not, top members of the U.S. government have signaled they are.

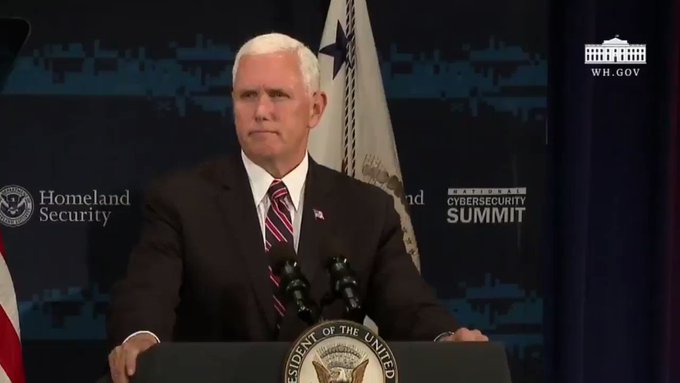

At a national cybersecurity conference in July, Vice-President Mike Pence made clear the government’s focus on offensive attacks.

“Resilience,” Pence said, “isn’t enough. We must be prepared to respond.”

Pence explained the government’s own vision further, saying, “Our administration has taken action to elevate the United States Cyber Command to a ‘combatant command,’ putting it on the same level as the commands that oversee our military operations around the world. Gone are the days when America allows our adversaries to cyberattack us with impunity.”

Most security experts agree with some of the major points issued by Cyber Command and by government officials like Pence. Attempts at interference and disruption online have changed, and the need for updated rules and procedures to deal with these issues need to evolve as well. Allowing the military a clearer, faster protocol for dealing with attacks sounds wise, but just where the limits are remain unclear. The Cyber Command vision statement is just that — a vision. Academics critical of the PPD-20 rescinding, like Stanford cybersecurity experts Herb Lin and Max Smeets, are calling for greater clarity.

“The vision doesn’t address what that [gaining strategic advantage] actually means and how much it will cost,” they wrote. As it stands, the language used both by Cyber Command and Pence suggests an emphasis not on stability, but on victory. But as Lin and Smeets note, “winning” cyberbattles may keep the United States on top, but does little to end that larger issue of persistent online war. “A United States that is more powerful in cyberspace does not necessarily mean that it is more secure.”

In terms of actual policy decision and accountable legal frameworks, the Trump administration and the military remain relatively silent — at least publicly. However unlikely the thought of the U.S. launching a successor to NotPetya may be, without clear language specifically limiting these types of weapons, it’s difficult to predict what safeguards are in place to prevent that situation.

The rescinding of PPD-20, regardless of what may replace it, signals a watershed moment for how the United States engages in cyberwarfare, who it is willing to target, and what methods it is willing to use.

“I wrote the first history book on this,” Healey said, reflecting on the weight of this moment in context. “I suspect that when I write the second or third version, 2018 is going to be one of the turning points for when things get better or worse. The U.S. has said, ‘The gloves are off.’”

No comments:

Post a Comment