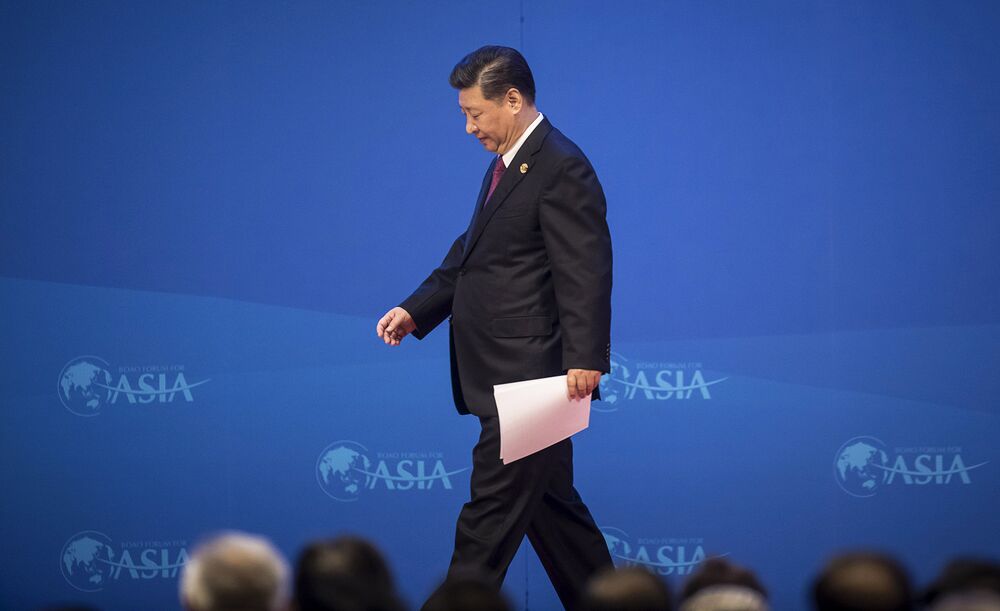

A few months ago, Xi Jinping seemed unstoppable. He’d just abolished presidential term limits and announced the most sweeping government overhaul in decades. Having hosted Donald Trump for a successful visit in November, Xi seemed to have prevented a trade war with the U.S. Party propagandists were distributing hagiographic accounts of the newly anointed leader for life. Today, China’s president looks like he may have overreached. An economic slowdown, a tanking stock market, and an infant-vaccine scandal are all feeding domestic discontent, while abroad, in Western capitals and financial centers, there’s a growing wariness of Chinese ambitions. And then there is the escalating trade war with the U.S. China initially refused to believe it would happen, but in the past few weeks it’s become the prism through which Xi’s perceived failings are best projected.

A few months ago, Xi Jinping seemed unstoppable. He’d just abolished presidential term limits and announced the most sweeping government overhaul in decades. Having hosted Donald Trump for a successful visit in November, Xi seemed to have prevented a trade war with the U.S. Party propagandists were distributing hagiographic accounts of the newly anointed leader for life. Today, China’s president looks like he may have overreached. An economic slowdown, a tanking stock market, and an infant-vaccine scandal are all feeding domestic discontent, while abroad, in Western capitals and financial centers, there’s a growing wariness of Chinese ambitions. And then there is the escalating trade war with the U.S. China initially refused to believe it would happen, but in the past few weeks it’s become the prism through which Xi’s perceived failings are best projected.

China watchers say studying the workings of the Communist Party is like trying to review a play by watching only the audience’s reaction. By that gauge, signs of upheaval are reverberating around Beijing during what is fast becoming Xi’s summer of discontent: articles from prominent academics and pundits questioning his overall policy direction; an embarrassing rebuke of his top economic adviser by Trump; and a rare public spat over policy between the central bank and Ministry of Finance. All point to a newfound sense of self-doubt creeping into a country whose relentless march to becoming a global superpower had seemed unstoppable. “The trade war has made China more humble,” says Wang Yiwei, a professor of international affairs at Renmin University in Beijing and deputy director of the institution’s “Xi Jinping Thought” center. “We should keep a low profile,” he says, even suggesting that China should rethink how it implements Xi’s flagship “Belt and Road” infrastructure project.

That’s a remarkable shift in sentiment from March, when Xi boasted of taking China closer to the center of the world stage at the National People’s Congress and secured near-unanimous support for scrapping term limits. Yet that’s also when the whispers began, as some throughout the country, from young officials to old cadres, were shocked at the suddenness of Xi’s power grab.

In May, entering trade negotiations with the U.S., China projected swagger and self-confidence. Xi dispatched Liu He, his top economic adviser, to the U.S. with the official designation of his “personal envoy.” Liu returned to proclaim victory: There would be no trade war, he said in nationally televised interviews. Then came the shock. Trump imposed $50 billion in tariffs on China. That’s since escalated to a threat to impose a 25 percent tariff on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods, prompting the country to warn the U.S. against “blackmailing” it over trade. Meanwhile, a slowing economy makes China more vulnerable to damage from a trade war, which economists predict could cut as much as half a percentage point from growth.

Chinese academics, economists, and some officials have begun to question whether the leadership could have done more to avoid the confrontation. As carefully worded essays circulate on the WeChat forum, the grumbling has begun to echo around the halls of government. One Finance Ministry official says China made a “major misjudgment” of Trump’s determination to confront the country. Others wonder if China underestimated the durability of American power. “The U.S. will use its hegemonic system, established since World War II from trade, finance, currency, military, and so on, to stop the rise of China,” Ren Zeping, chief economist at China Evergrande Group, wrote in one widely read commentary published on June 5.

“Rising anxiety has spread into a degree of panic throughout the country”

As officials and scholars look around the world, they see widespread skepticism of Chinese ambition, particularly in Western capitals whose governments are taking measures to limit China’s ability to buy strategic assets. If this is China’s moment, officials ask, how is it the new superpower seems so alone? “There was a broad-based consensus building that China’s behavior was predatory and needed to be stopped,” says Jude Blanchette, who analyses Chinese politics at Crumpton Group LLC, an international advisory and business development firm in Arlington, Va. “The casting off of term limits was a match on that gasoline and has acted as an accelerant for pushback in the U.S.”

China has begun to rein in its swagger, starting with the propaganda system. State media were told to downplay the Made in China 2025 industrial initiative to become the world’s foremost power in 10 important industries, including artificial intelligence and pharmaceuticals, a plan the U.S. has identified as a key threat. They were also instructed to avoid talking about China’s greatness (the Chinese title of one recent blockbuster movie translates as “my country is awesome”). The push is to focus instead on how China has helped other nations, according to a person familiar with the instructions.

Europeans, still deeply skeptical of Chinese industrial policies, are pressing for pledges of greater reciprocal market access to be made more concrete and tougher screening of Chinese investments inside the 28-nation bloc. EU officials say they agree with Trump on the substance of his criticisms, even if tariffs aren’t their preferred weapon. “The EU is open, but it is not naive,” European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker told a July session of business leaders attended by Premier Li Keqiang in Beijing.

Domestic criticisms have intensified, too. “People across the nation, including the entire bureaucratic elite, feel increasing uncertainty about the direction of the country and a deep sense of personal insecurity,” wrote Xu Zhangrun, a law professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing, in a July 24 essay on the website of the Unirule Institute of Economics, a Chinese think tank. “Rising anxiety has spread into a degree of panic throughout the country.”

Domestic policy dust-ups, from fresh outrage against failed peer-to-peer lending services to a rushed transition from coal that left millions of villagers without heat, are beginning to look like the inevitable outcome of a system where decision-makers are isolated from facts on the ground. Some began to look back nostalgically to a time when keeping a low profile was seen as a key part of making China great again.

After the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, China began a global charm offensive. The mantra then was to follow former leader Deng Xiaoping’s maxim: China should hide its strength and bide its time. Officials and scholars are starting to talk wistfully of Deng’s guidance. That strategy “allowed China to pursue wealth and power in a way that stayed below the radar,” says Crumpton’s Blanchette. “By casting that off so forcefully, it’s exposed China to many of the global forces it’s now being battered by.”

While Xi may have lost some of his ability to inspire confidence among his people, he is more capable than ever of inspiring fear. His anticorruption campaign has netted more than 1.5 million officials. And there are no outwardly visible signs of organized opposition to him in the party. Even if everyone is clear that Xi isn’t perfect, there are costs for saying so. “It is too soon to reevaluate Xi’s position,” says David Cohen, a Beijing-based managing editor at consulting firm China Policy. “It is clear that whatever doubts people might have about Xi as a person, there is broad agreement on the biggest areas of policy.”

Still, there is a sense in which the last month has felt like the end of the beginning for Xi Jinping. “There is suddenly a burst of open discussion and criticism, and it’s very dramatic compared with what we’re used to under Xi,” says Cohen. “People below think there’s more room to push back.”

No comments:

Post a Comment