A sharp slowdown in investment this year points to a more subdued future

CHINA does not do infrastructure by half measures. It has the world’s longest networks of motorway and high-speed rail (which Hong Kong joins on September 23rd, see article). It has the tallest bridge as well as the longest. It is building nearly ten airports a year, more than any other country. It has the most powerful hydroelectric dam, the biggest wind farm and as much coal power as the rest of the world combined.

But the infrastructure boom has lost steam this year. After expanding at a double-digit pace for much of the past three decades, investment in it has slowed sharply. Since May spending on projects ranging from railways to power plants has fallen compared with a year earlier, the longest weak patch on record.

The question is whether this is a blip or a fundamental change. Some analysts argue that the decline in spending is only short-term, related to the government’s efforts to rein in debt. As the trade war with America rumbles on (see article), they expect that China will try to boost the economy with another burst of infrastructure-building. But many others believe that even if this were to be attempted, it would not work. Their argument is not that investment should stop. China still usefully spends more in two months on such things as building roads and ports and laying cables than India manages in an entire year. Rather, they say, building at an even greater rate would risk outstripping demand. It is time to find other ways of fuelling growth.

The recent infrastructure-spending slump certainly relates to efforts to curb the country’s massive build-up of local-government debt. Many cities had been borrowing heavily, often using murky channels, to build flashy transport systems. A crackdown on shadow banking has left them short of funds. The central government has also targeted spendthrifts. Last year it ordered a halt to the construction of a subway in Baotou, a city in Inner Mongolia, a northern province where government debts are sky high.

But the slowdown is not just because of a short-term squeeze. Chinese officials are also becoming more conservative in their planning. In July the government decreed tough new standards for subway systems. Cities must have a population of at least 3m to qualify for one. They must also have their debts under control, and cover at least 40% of building costs from their own revenues.

In recent weeks big cities with much healthier economies than Baotou’s have scaled back their subway plans, too. One example is Chengdu, the booming capital of Sichuan province, which has produced a revised blueprint for its transport system. It features six fewer subway lines than had previously been planned.

Nantong, a city about 150km north of Shanghai, demonstrates both China’s prowess in infrastructure and what seems to be a newfound restraint. Builders are close to completing a cable-stayed bridge (pictured) that will be the longest of its type in the world. Yet at the same time Nantong has tempered its ambitions. Its urban centre is home to 2m people, spread over anarea larger than London, below the required population for a subway system. It was already building its first line when the rules came into effect, and was allowed to continue with that and a second one.

But even without the new edict, Nantong had been having second thoughts. The city’s traffic already flows well. Zhong Qingwen says she is typical in getting from her home to her office, at a medical-testing company, in less than 20 minutes by bus. The city had been planning eight urban-rail lines. Their combined length of 330km would have surpassed that of Tokyo’s subway. Now the government is moving more slowly. The first line will not be finished until 2022, four years later than the original target. Beyond the second one, further expansion is off the table for now.

One reason why many cities had such big dreams was because they expected a white-hot economy and a rapid influx of migrants from the countryside. Rising demand had seemed more or less assured. But both economic growth and the pace of urbanisation are tailing off. Spending on infrastructure still accounts for a fifth of China’s annual output, far above the level of most other countries. Liu Shijin, a member of the central bank’s monetary policy committee, said at a conference this month that the economic benefits of this were waning fast. Instead, he suggested, the government should spend more on health care and welfare.

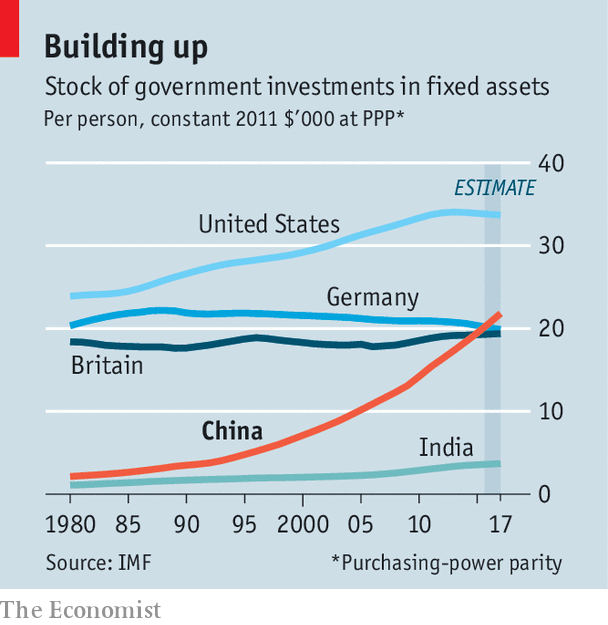

Mr Liu may well be right. China’s stock of government-invested fixed assets—a proxy for infrastructure—is already about the same per person as Germany’s or Britain’s, according to IMF data that use exchange rates adjusted for purchasing power. The stock is much greater than in other countries at China’s income level. It is well behind America’s, but it would have caught up within a decade had China continued spending on infrastructure at its previous feverish rate (see chart). Even the rosiest projections of China’s infrastructure needs suggest that demand will slacken. Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics, a London-based research firm, says investment growth will slow to low single digits.

Mr Liu may well be right. China’s stock of government-invested fixed assets—a proxy for infrastructure—is already about the same per person as Germany’s or Britain’s, according to IMF data that use exchange rates adjusted for purchasing power. The stock is much greater than in other countries at China’s income level. It is well behind America’s, but it would have caught up within a decade had China continued spending on infrastructure at its previous feverish rate (see chart). Even the rosiest projections of China’s infrastructure needs suggest that demand will slacken. Julian Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics, a London-based research firm, says investment growth will slow to low single digits.

Yet the current slowdown has gone too far for the government. After a meeting on September 18th China’s cabinet called for more “efficient” investment. Having slammed on the brakes to control debt, the central government is now making it easier for fiscally responsible localities to spend on infrastructure. It has resumed approvals of some large projects. It has also encouraged banks to buy local-government bonds, including ones earmarked for infrastructure spending.

As a result, the flow of money into subways, bridges and the like may increase slightly, says Yao Wei of Société Générale, a French bank. But Ms Yao reckons that the voices for prudence will win out, even if the trade war with America begins to take a bigger toll on the economy. Unlike in the past, China will, she predicts, play it safe on debt and let growth slide.

One dividend from China’s past infrastructure-building sprees has been the expertise it has gained in construction work. In Nantong a site managed by the China Railway Group, a state-owned company, is immaculate. Workers stand in front of a body-length mirror to check their safety gear. Cranes lay down a latticework of metal poles nearby to reinforce the terrain. A sign declares that it is a “100-year project”—a subway that should long serve the city. After a mad rush to build, China is also learning to live within its means.

This article appeared in the China section of the print edition under the headline "Life in a slower lane"

No comments:

Post a Comment