By Samuel Ramani

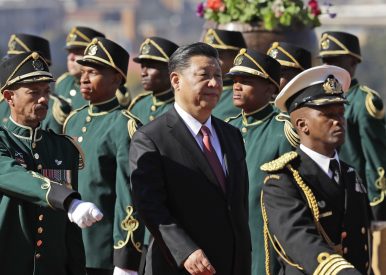

On August 24, Major General Shao Yuanming, the deputy chief of staff of China’s Central Military Commission’s Joint Staff Department, arranged a meeting with South Africa’s military chief Solly Shoke in Beijing to enhance bilateral security cooperation. This meeting gained widespread international attention, as it underscored China’s solidarity with South Africa in the aftermath of U.S. President Donald Trump’s criticisms of the South African government’s plan to redistribute farmland, which is mostly held by white farmers.

On August 24, Major General Shao Yuanming, the deputy chief of staff of China’s Central Military Commission’s Joint Staff Department, arranged a meeting with South Africa’s military chief Solly Shoke in Beijing to enhance bilateral security cooperation. This meeting gained widespread international attention, as it underscored China’s solidarity with South Africa in the aftermath of U.S. President Donald Trump’s criticisms of the South African government’s plan to redistribute farmland, which is mostly held by white farmers.

The Chinese government can use the controversy over Trump’s comments as an opportunity to counter rising negative perceptions of China amongst the South African public. South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC)-led government has addressed these criticisms of China by arguing that the Beijing-Pretoria alignment has bolstered South Africa’s influence in world affairs, and by emphasizing China’s historic support for racial equality in South Africa.

South Africa’s Increasingly Negative Perceptions of China

Although China-South Africa trade volumes have steadily increased in recent years and China strongly supported South Africa’s accession to the BRICS group of emerging economies in 2010, China continues to be viewed with suspicion by the majority of South Africans. An August 2017 Pew Research Center survey revealed that only 45 percent of South Africans had a favorable opinion of China’s role in the world. This level of support for Chinese foreign policy lagged behind all other African countries represented in the survey, and was lower than the 53 percent of South Africans who viewed the United States as a constructive force in international affairs.

The South African public’s skepticism about China’s intentions can be explained by two main factors. First, many South Africans believe that China interferes in their country’s internal affairs by providing financial assistance to the ANC. These suspicions surfaced after the 2009 national elections, when South African opposition parties accused the ANC of accepting campaign contributions from Chinese donors. These donations have been linked to South Africa’s unwillingness to criticize China’s human rights record in major multilateral forums like the African Union, the UN Security Council, and the G20.

The ANC’s decision to disengage from its long-standing criticism of Chinese government human rights abuses in Tibet has been viewed by critics as proof of China’s growing infiltration into South African political life. South African President Jacob Zuma decided to block the Dalai Lama’s entry into South Africa in 2009, causing a great deal of political backlash against the ANC. The late Nelson Mandela and his grandson strongly condemned this entry ban.

Despite this backlash, the ANC blocked the Dalai Lama’s entry once again when he announced his intention to visit South Africa in 2014. After this decision, the ANC’s political rivals expressed strong opposition to Beijing’s growing influence over South African foreign policy. This opposition culminated in the right-wing Inthaka Party’s February 2018 decision to invite the head of Tibet’s government-in-exile, Lobsang Sangay, to South Africa. The ANC’s criticism of Sangay’s visit sparked further allegations of Chinese interference in South African politics from the liberal Democratic Alliance Party, which South Africa’s new President Cyril Ramaphosa has struggled to credibly address.

Second, the ANC’s critics believe that China’s model of governance has influenced South Africa in a negative way. During Zuma’s tenure as president of South Africa from 2009-2018, some opposition activists alleged that Zuma was modelling the ANC after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to prolong the party’s political hegemony. These claims resurfaced again when ANC Secretary General Ace Magashule announced on July 30 that the Chinese Communist Party would train ANC members ahead of the 2019 South African elections.

After Magashule’s announcement, Fikile Mbalula, a member of the ANC national executive committee, criticized the CCP’s training program and claimed that China was encouraging ANC members to engage in propaganda that is typically associated with authoritarian states. As Zuma was widely criticized for reducing government transparency and diluting the South African constitution to advance ANC interests, many South African civil society activists view the growth of Chinese influence over South Africa as a trigger for further democratic breakdown, and have become increasingly hostile toward Beijing.

The ANC’s Efforts to Rehabilitate China’s Image

In response to criticisms of the Beijing-Pretoria connection, senior ANC officials refuted allegations that South Africa has entered into a neocolonial partnership with China. Instead, ANC foreign policy strategists have argued that China is seeking to create a multipolar world order, which would resist the “wrath of U.S.-led Western imperialism,” and give non-Western powers greater influence over world affairs.

To demonstrate that South Africa’s alignment with China has bolstered Pretoria’s international standing, ANC officials highlight China’s efforts to give South Africa a position of prominence within BRICS. The ANC has described South Africa’s participation in BRICS as the prime example of its foreign policy agenda of “progressive internationalism,” which seeks to promote uniquely South African values within global governance institutions.

Ramaphosa has argued that China’s encouragement of South Africa’s participation in BRICS demonstrates that Beijing is committed to helping Africa gain an independent voice in world affairs. From the ANC’s perspective, South Africa’s agreement with Beijing on opposing the 2011 overthrow of Libyan dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi and on preventing UN sanctions from being imposed on Zimbabwe demonstrates a synergy of normative positions that acts as a basis for durable bilateral cooperation.

The ANC has also attempted to improve China’s image in South Africa by emphasizing the Chinese government’s longstanding support for racial equality in South Africa. Although the Soviet Union was the ANC’s leading international sponsor during the apartheid era, China strongly supported the Pan-African Congress, which sought to achieve black majority rule in South Africa through the adoption of socialist principles. China’s support for ending apartheid contrasted markedly with the acquiescence of the United States and United Kingdom to white minority rule until the 1980s, and bolsters the credibility of ANC claims that China is a genuine ally of South Africa.

In spite of growing discontent with China’s perceived interference in South African internal affairs and the negative influence of Beijing on South African democracy, the ANC believes that South Africa’s ties with China should remain a fulcrum of its foreign policy agenda. If Ramaphosa can prevent the Beijing-Pretoria relationship from becoming a divisive issue during the 2019 national elections, the China-South Africa partnership will likely continue to strengthen for the foreseeable future.

Samuel Ramani is a DPhil candidate in International Relations at St. Antony’s College, University of Oxford. He is also a contributor to The Washington Post and The National Interest. He can be followed on Twitter at samramani2 and on Facebook at Samuel Ramani.

No comments:

Post a Comment