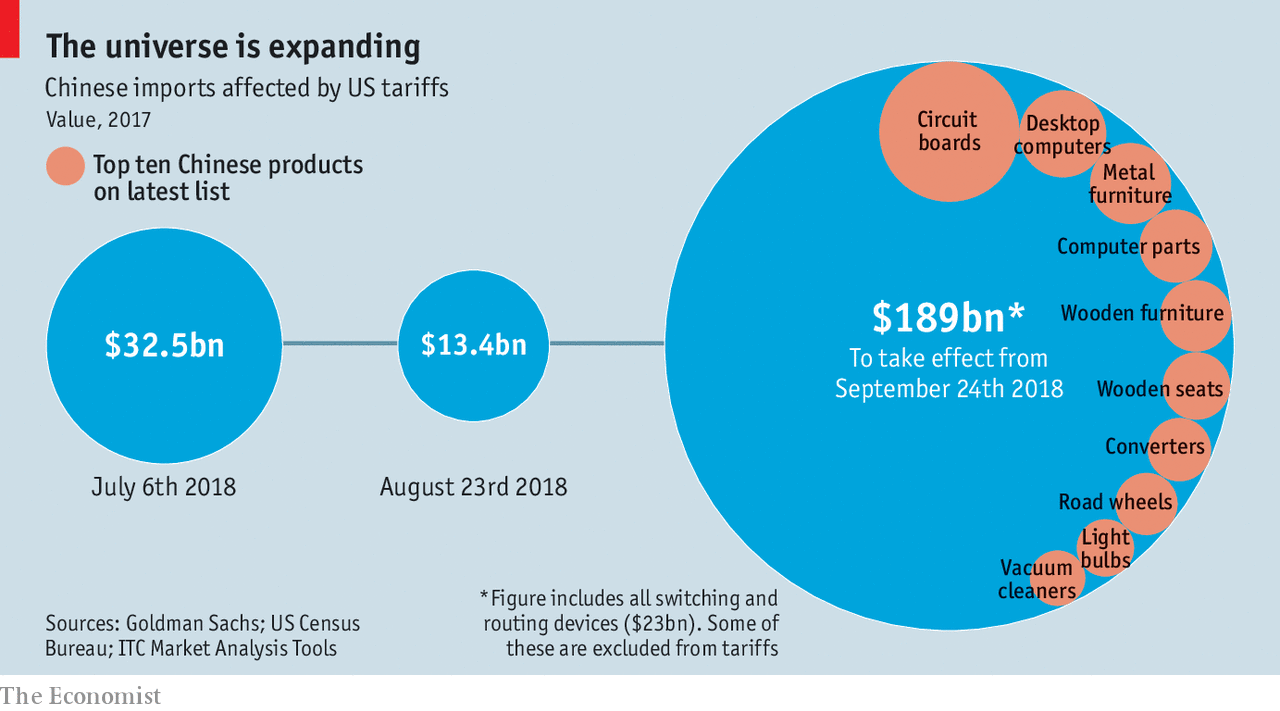

ANOTHER week, a further ratcheting up of trade tensions between America and China. On September 17th President Donald Trump announced that he had approved a further wave of tariffs on Chinese imports. From September 24th, imports of products which in 2017 were worth as much as $189bn, including furniture, computers and car parts, will be hit with duties of 10%. The Chinese have promised to retaliate on the same day with duties on $60bn of American exports. Unless peace breaks out before the new year, the American rate will increase to 25% on January 1st.

ANOTHER week, a further ratcheting up of trade tensions between America and China. On September 17th President Donald Trump announced that he had approved a further wave of tariffs on Chinese imports. From September 24th, imports of products which in 2017 were worth as much as $189bn, including furniture, computers and car parts, will be hit with duties of 10%. The Chinese have promised to retaliate on the same day with duties on $60bn of American exports. Unless peace breaks out before the new year, the American rate will increase to 25% on January 1st.

Mr Trump frequently rants about how the Chinese have long taken advantage of Americans. But American bureaucrats stress that the duties come after careful deliberation. The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) took seven months to write a report detailing China’s unfair trade practices. Each tranche of tariffs has been consulted on and then revised. The latest set came after the USTR’s office had received 6,000 written submissions and held six days of hearings.

Compared with an earlier proposal, the latest tariff list excludes products worth up to $30bn. Child-safety seats and safety headgear were exempted. Antiques more than a century old were spared, too. (Some had pointed out that the Chinese government restricted their export anyway.) Despite Mr Trump’s warning on September 8th that prices of products made by Apple may increase as a result of his tariffs, smartwatches and bluetooth devices were removed from the list.

The Trump administration claims that these deliberations have helped to minimise the impact on the American consumer. The staggered tariff rate is supposed to give importers time to change their suppliers. Wilbur Ross, the commerce secretary, was mocked online for claiming that, because the tariffs are spread over thousands of products, “nobody’s going to actually notice it at the end of the day”. But in support of his claim, economists at Goldman Sachs, a bank, estimate that the 10% tariff rate will boost inflation by only around 0.03 percentage points, and the increase to 25% by a further 0.05 next year.

Still, this diligence was not welcomed by all. More than three-quarters of the products that will be affected on September 24th are intermediate and capital goods, which means the most immediate impact will be to push up American businesses’ costs. Mr Trump’s announcement triggered complaints from industry representatives including the US Chamber of Commerce, the American Chemistry Council and the American Apparel and Footwear Association, all of which warned that Americans would end up footing the tariff bill, and pleaded for a different approach.

Although it claims to be following due process, the Trump administration’s actions are far removed from the procedures of the rules-based global trading system. Ordinarily, members of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) would take their complaints to the body’s judges. If such accusation are upheld, then those judges allow limited retaliation.

In 2012, for example, the American government complained to the WTO that the Chinese government was breaking the rules by restricting the export of rare-earth elements. China’s dominance in their global supply meant that this hurt American manufacturers by pushing up prices for their inputs. After the WTO’s judges sided with the Americans, the Chinese government dropped the measures.

The Trump administration claims that the WTO’s incomplete rule book makes it incapable of dealing with China’s alleged misdemeanours, which include forcing foreign companies to hand over their technology. But, even as it complains, America is simultaneously weakening the system by which the WTO’s rules are enforced, by blocking the appointment of judges to the body’s court of appeals. From October, only three will be left—the minimum needed to rule on a case.

On September 18th Cecilia Malmström, the European Union’s trade commissioner, unveiled a “concept paper” outlining reforms that could plug some of the gaps in the WTO’s rules, as well as ways to reform dispute settlement. But it is far from clear whether either Mr Trump or the Chinese government will take the bait.

And without the multilateral rules-based system to contain the conflict, the trade war between China and America could get much bloodier. In his announcement on September 17th Mr Trump threatened to hit another $267bn-worth of Chinese imports if China retaliated against his latest tranche of tariffs. For their part, the Chinese show little sign of backing down, and have promised to use fiscal policy to soften any domestic blow.

Although they are running out of American exports to target, they have other ways to fight. On September 17th, for example, reports emerged of a Chinese official musing about China repeating its trick of imposing export restrictions on raw materials that American manufacturers depend on. The next day, Craig Allen, president of the US-China Business Council, warned that the WTO had made clear its opinion that such restrictions were illegal. But why, when America is acting outside the rule book, should others stick to it?

Correction (September 21st 2018): The original version of this article referred to Craig Allen as the chairman of the US-China Business Council. He is its president. Sorry.

No comments:

Post a Comment