Lt. Col. Matthew T. Archambault

Leaders from across 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, representing three different generations of education, training, and experience, work on the final fight of the Leader Training Program, Fort Irwin, California, November 2016. (Photo by Capt. Eileen Hernandez, U.S. Army) Doctrine receives mixed reviews from leaders across the Army. Mythology surrounds doctrine like a fog. Many junior leaders reiterate the quip, sometimes attributed to the Soviets, that Americans are unpredictable because we don’t follow our own doctrine.1 These leaders implicitly associate the reputed quote with the idea that strategy or fundamentally sound tactics do not matter.

Leaders from across 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, representing three different generations of education, training, and experience, work on the final fight of the Leader Training Program, Fort Irwin, California, November 2016. (Photo by Capt. Eileen Hernandez, U.S. Army) Doctrine receives mixed reviews from leaders across the Army. Mythology surrounds doctrine like a fog. Many junior leaders reiterate the quip, sometimes attributed to the Soviets, that Americans are unpredictable because we don’t follow our own doctrine.1 These leaders implicitly associate the reputed quote with the idea that strategy or fundamentally sound tactics do not matter.

Setting aside what is taken by many as recieved wisdom, though doctrine may be far from perfect, it does contain essential fundamentals professionals must master in order to not only be successful but also to be worthy of the title “professional.” For example, units training at the Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) at Fort Polk, Louisiana, succeed or fail based upon their mastery of the fundamentals outlined in doctrine. Prior to each unit’s rotation, unit key leaders attend the Leader Training Program, a week dedicated to commanders and staffs refreshing on planning fundamentals. During this training, the commander of the operations group briefs them on the latest observed trends. Heads invariably nod at each trend, but when units arrive for their rotations, there is little evidence that their leadership addressed those trends.

This article focuses on one trend I have observed regarding the “struggle to move from conceptual planning to detailed planning.”2 Commanders put out guidance, the level of directness and clarity varies, but regardless, often the staff is incapable of achieving the appropriate level of detail in their planning.

Figure 1. Integrated Planning (Graphic from Army Doctrine Reference Publication 5-0, The Operations Process, 2012)Enlarge the figure

Failure to achieve the requisite planning detail is a three-generation dilemma that requires all the generations present in a unit—company grade officers, field grade officers, and senior (battalion and brigade) commanders—to solve collectively. To eliminate this trend, commanders must acknowledge the experience gap between themselves and their subordinates, and actively develop their staffs by engaging those staffs to solve the problems confronting their organizations. On the other hand, subordinates must support the collective effort by assuming personal responsibility for identifying their own knowledge gaps.

Detailed Planning

Detailed planning requires detailed explanation; otherwise, planning remains abstract and merely conceptual rather than practically useful in application. As noted in Army Doctrine Reference Publication 5-0, The Operations Process, planning exists on a continuum from conceptual at one end to detailed planning on the other (see figure 1). Detailed planning, specifically, is “the science of control, including movement rates, fuel consumption, weapons effects, and time-distance factors.”3

Staff members representing their warfighting functions ought to capture the necessary details in their running estimates. Practical experience at the JRTC highlights that understanding the relationship between details in plans leads to realization of risk and identification of where shortfalls may lie. The identification of these relationships occurs during the military decision-making process (MDMP) and specifically during mission analysis. Unfortunately, ineffective MDMP and current running estimates are an observed trend at JRTC, but that is only part of the conceptual-to-detail conundrum. Nearly all of the negative trends revealed at the JRTC during field exercises relate to a lack of detailed planning, whether it be in clearly defining reporting requirements during reception, staging, onward movement, and integration; publishing graphics for a common operating picture; or putting in place a system to rapidly clear ground and air for effective fires.4 Practical experience constantly exposes that the need for detailed planning is acute.

Experience

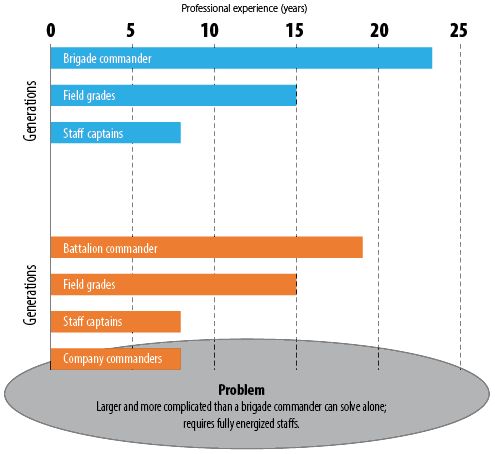

Sometimes the obvious, what is right in front of us, escapes us. Brigade commanders have more experience than their staffs. Everyone knows that. Consequently, many commanders often remind their subordinates they will command by deciding matters based on their own experiences. However, the gap in experience between commanders and their staffs and subordinates is significant. An average brigade commander will have more than twenty-two years of experience. By comparison, the field grade officers will have no more than twelve to fifteen years, and the staff captains, doing the yeoman’s work, will usually have five to seven years in the Army (see figure 2).5 These are the three generations in a battalion or brigade.

Figure 2. The Three-Generation Dilemma (Graphic by author)Enlarge the figure

Aggregate experience itself is not the only differentiation among generations. Seen through the lens of the cognitive domains, commanders operate higher on Bloom’s pyramid than subordinates, not because they are smarter, but because they have a broader base of experience that allows them to evaluate and synthesize.6 On the other hand, captains know MDMP. They know it as well as the three repetitions they executed during Maneuver Captains Career Course. Also, field grade officers know MDMP from what they remember when they were at the course, which in turn has been reinforced from iterations at combat training centers (CTCs).

The commanders, whether lieutenant colonel or colonel, likely have many more iterations, probably also accrued at CTCs. Enriching their collective execution of MDMP is all of their other experiences in the ensuing years; field problems, CTC rotations, real-world deployments, and more. Therefore, from an optimal perspective, with everything being equal, the commander and staff have common experiences, which enable a shared implicit language. However, they are separated by a difference in the number of repetitions and variety of those experiences under varying conditions.

So MDMP begins. Staff duties and responsibilities are generally clear. Commanders know their tasks within mission command; the first being to “drive the operations process through their activities of understanding, visualizing, describing, directing, leading, and assessing operations.”7 Staffs know their tasks to support the commander. The first breakdown begins with whether the commander leverages and develops the staff. Commanders are inclined to be conceptual. They have survived the staff trenches and want to revel in the art of command, but they cannot remain aloof from the science, which in effect means the details. The experience gap between a commander and the staff demands a deliberate approach to developing that staff to be an effective tool to accomplish their tasks of conducting the operations process, managing knowledge and information, and synchronizing information-related capabilities.8 The deliberate approach a commander takes benefits the unit at that moment and helps respond to the three-generation dilemma in the longer term.

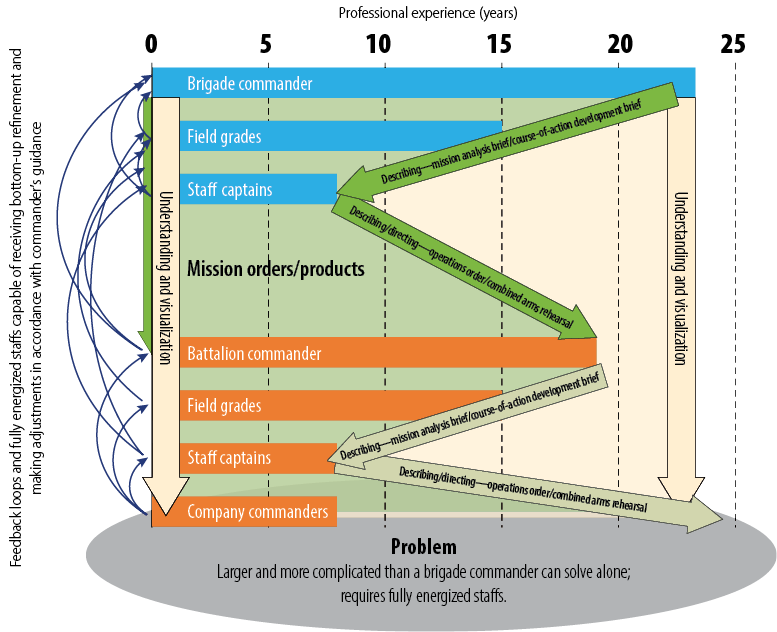

The deliberate approach involves the commander actively describing his understanding and visualization of the problem to the staff. The staff, in turn, shares that vision with and produces mission orders for battalions, which replicate the process. At every level, staffs can facilitate achieving their commander’s intent because they understand what he or she is visualizing. Coming from within the mission command principles, the commander and staff have shared understanding. Figure 3 depicts the optimal scenario.

Figure 3 only attempts to illustrate the commander’s role in the operations process—principally to understand, visualize, describe, direct, lead, and assess—through the lens of experience.9 A commander’s understanding and visualization happens as a result of staff estimates compiled in a mission analysis brief as well as from his or her own experience. The problems organizations face are generally larger and more complicated than leaders can handle alone. If the situation were not thus, commanders would not need staffs. Staffs provide crucial information to their commanders and help their commanders achieve understanding. Additionally, it is often through quality dialogue between commanders and their staffs that visualization emerges. Hence, no one should interpret this model to mean commanders provide answers to their staffs.

Figure 3. Commander Bridging the Generations (Graphic by author)Enlarge the figure

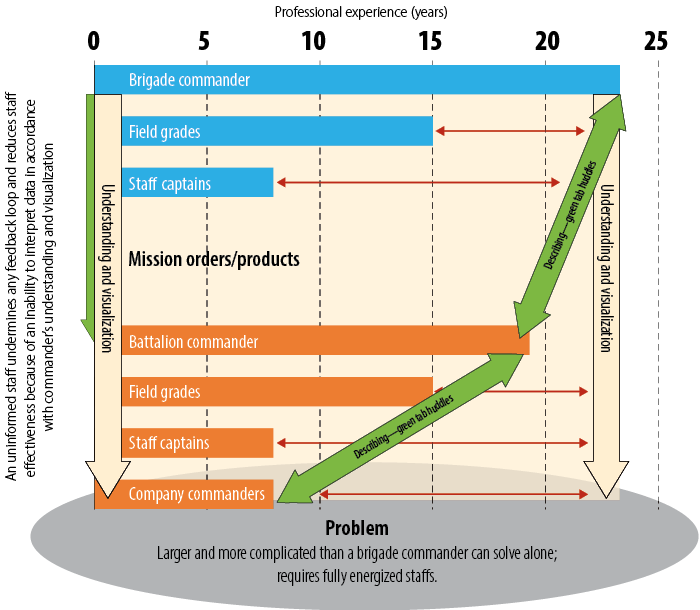

The green field in figure 3 is the realm of “describing,” just as the green arrows labeled “describing” are the opportunities provided by MDMP for a commander to actively develop the staff. Doctrine is clear that “the commander is the most important participant in MDMP” and must “use his experience, knowledge, and judgment to guide staff planning efforts.”10 The operative word is guide. Guide implies the commander is not providing a directed course of action and expecting the field grade officers to create the necessary products for its implementation. Products are necessary, but so is the knowledge of how the commander came to the visualization and understanding. Guide also implies the commander is not ignoring the staff and leveraging only the subordinate commanders in discussions. Both of these situations are common observations during rotations at JRTC. Figure 4 illustrates these occurrences, in contrast to the optimal situation depicted in figure 3.

The model in figure 4 illustrates a situation where describing and directing only occurs between commanders. Staffs are not privy to the decision made between commanders, resulting in an inability for them to act on their commander’s behalf. The red arrows reflect the risk assumed from this approach as the experience gap persists. Risks manifest themselves in many forms. In the immediate, field grade officers and staff captains, without their commander’s development and investment, cannot be proactive. Critical staff actions and synchronization do not occur and the staff does not discover critical details that could inform the commander’s understanding of the battlefield. Worse, from a generational perspective, is that these junior leaders lose an opportunity to further their development. Having the prescribed conversations directed by MDMP is a development opportunity for those future field grade officers and commanders.

Vignette

The “Get-It-Done” Brigade is executing its combined arms rehearsal (CAR) for the brigade’s defense, which begins in earnest six hours from now. Present at the CAR are all of the battalion commanders, their command sergeants major (CSMs), their battalion S-3s (operations officers), and the brigade staff. The brigade (BDE) S-3 leads the CAR from his script.

BDE S-3: We will now cover Phase IIIA, which begins with Red Battalion’s breach of obstacles in vicinity of Objective Hedgehog and concludes with the White Battalion consolidating on Hedgehog North and the Blue Battalion consolidating on Hedgehog South.

[The CAR is happening in a small clearing adjacent to the Brigade Tactical Operations Center. A generator twenty feet away drowns out the BDE S-3’s voice for the crowd on the far side of the terrain model. No one can effectively hear what’s being discussed except for Col. A. Tack and his battalion commanders seated around him. In that far side crowd, two brigade planners, both captains, both precommand, stand with their green notebooks open and pens at the ready.]

Figure 4. Commander Bypassing the Staff (Graphic by author)Enlarge the figure

Capt. Saul Tee: Did you catch those changes the commander wants?

Capt. Bo Ord: What? No. I’m sure the Three will tell us what to do. I don’t even know why we’re here.

Capt. Saul Tee: We might be needed for something.

Capt. Bo Ord: You mean like moving these placards out on the terrain model? Joe should be doing this. I didn’t think staff would be this bad. What a waste of time.

Capt. Saul Tee: It’ll be better when we’re company commanders.

BDE S-3: … Decisive to this phase is an effective breach by Red and forward passage of lines of White and Blue. Decision points during this phase include the commitment of the reserve to …

Col. A. Tack: Three, I’m going to stop you there. Sorry, I didn’t keep you up-to-date. Commanders and I huddled last night. We think two breaches on Hedgehog by White and Blue. Red clear the route to the release point and adopt a follow and assume posture. Based on his combat power, this makes more sense. Isn’t that right Red 6?

Red 6: Roger that sir. We have …

[The BDE XO (executive officer) walks up behind the BDE S-3.]

BDE XO: Did we have anyone at that meeting?

BDE S-3: I wasn’t tracking it. Were you? I was building this script.

BDE XO: Yeah. I thought you were. You could’ve sent Capt. Tee or Ord to it.

BDE S-3: Their notes would’ve been useless. They can’t make the simplest products like the EXCHECK [execution checklist]. I told them to do that and when I came back it was still empty. I did it myself.

BDE XO: Boss said he wanted …

Col. A. Tack: That’s perfect. Thanks Red 6. What’s really critical here is synchronization. We’re not going to execute this based on the clock. Events will drive our next steps as condition setting takes place. White and Blue cannot get their piece done, hell they can’t even get to where they get their piece done without the right conditions being set by …

[On the near side of the terrain model, right in the noise wash of the generator three of Blue’s company commanders stand actively taking notes and straining to listen.]

Capt. A. Merica: Once conditions are set we’re taking Hedgehog South? What conditions?

Capt. Lou Secannon: I’m not sure. We can ask the S-3 afterwards.

Capt. A. Merica: He doesn’t know. The commander will huddle with us after our CAR and we’ll get straight then. The S-3 is just there to make the staff …

Capt. Hardin DeHead: Make the staff do what? I haven’t gotten any graphics yet, have you? I’m not sure what the S-3 does. The only way I get anything is from talking to you guys. The staff is worthless.

Capt. Lou Secannon: Yeah, I don’t know why anyone would want to be on staff.

Capt. A. Merica: You have to be otherwise you can’t be a commander.

Capt. Hardin DeHead: Well, how do we not look as bad as our S-3?

Capt. A. Merica: You do what the commander wants. It’s that simple.

Capt. Lou Secannon: I never see him talk to the S-3 or XO. How are they supposed to know? They never seemed to understand what he wanted when I was on staff waiting for command.

Capt. A. Merica: You learn it at CGSC [Command and General Staff College].

Capt. Lou Secannon: I guess they didn’t learn it too good.

Capt. Hardin DeHead: When is this thing going to be over?

BDE S-3: Sir, this concludes the combined arms rehearsal. Pending yours and the CSMs’ guidance.

Col. A. Tack: Thanks Three. CSM?

CSM Noah Sense: Alright team. This is our Super Bowl! You hear me? This is our time. Whatever you got out of this, you better make sure your soldiers are ready to kick the hell outta da OPFOR [opposing forces]. It’s the killer instinct that wins on this field. It’s the will and you have it. Make sure your troopers are ready! Sir.

Col. A. Tack: Thanks sergeant major. I’m not sure I can do better. We discussed a lot out here. We caught some changes to the EXCHECK and synchronization matrix. The staff will push out the notes. Maybe we’ll roll it into a FRAGO [fragmentary order]. Most important though, I want you to remember four keys to success: (1) always be attacking, (2) violence of action when you’re attacking, (3) we’re attacking based on conditions being set, not on some random clock, and (4) if you’re confused about what to do next, attack. We’ll support you and mass our efforts behind you. Any questions of me?

[Silence. Except for the generator.]

Col. A. Tack: Great. Thanks staff. Let me see the commanders real quick to discuss a few things.

BDE: [in unison, salutes] Get it done!

Col. A. Tack: [returns salute] No matter what! Hooah!

[BDE XO huddles staff primaries on the other side of the terrain model from the congregating commanders.]

BDE XO: Okay, great job. Thanks for the hard work. I know everyone is tired, but before you run off, crawl beneath a trailer, and catch some shuteye, I want everyone to run down for me what you’re next priority is. S-1, you begin.

BDE S-1: We’re prepping casualty replacement packets. That’s the biggest thing.

BDE XO: Thanks. S-2?

BDE S-2: Priority one is the INTSUM [intelligence summary], which is due in an hour. After that, I caught the commander wanted an extra hour or so of GMTI [ground moving target indicator] during Phase II. I’ll coordinate with higher for it.

BDE XO: Okay. Let me know if you run into problems with that.

BDE S-3: He also mentioned the battalion scouts and their LLVI [low-level, voice intercept] teams. Did you catch that?

BDE S-2: I did, but that’s not for our collection plan. Those would be on the battalion-level collection plans.

BDE S-3: You’re right. My bad.

BDE XO: No worries. What did you catch?

BDE S-3: I’ve got a couple changes to the EXCHECK and SYNCH Matrix. I hate that thing. I wish the commander didn’t want them. I haven’t seen them since the Captain’s Career Course.

BDE XO: Same here, but the man gets what the man wants.

[At the green tab huddle …]

White 6: Isn’t this street Phase Line Orange?

Blue 6: That’s not the same street on my graphics. It’s not clear on the terrain model.

Col. A. Tack: Well, we can’t leave here with that confusion. Let’s go with what’s on White’s graphics. Is that a problem for you to change?

Blue 6: No sir. I can change it. We had an enemy templated in that house, which means it’s in White’s AO (area of operations) now. You can shoot it.

“

... the commander must acknowledge there is something for him to learn.

”

White 6: Is that your target or a brigade target?

Red 6: It’s not on the target list worksheet.

Blue 6: Yeah, but it’s on the terrain model. We just can’t tell which street is Orange.

Col. A. Tack: No worries gents. White, take the target. Too easy, right?

Battalion commanders [in unison]: Roger that sir.

Col. A. Tack: Great. Okay. Well, if there’s nothing else. I’m looking forward to a helluva battle. Get the troopers pumped up. It’s going to be hard, but it’s going to be fun.

All Things Not Being Equal

Ideally, experiences accrued along a typical officer’s timeline will arm that officer with the requisite knowledge to be successful at the next level. That’s the reason behind professional development timelines as outlined in the Department of the Army Pamphlet 600-3, Commissioned Office Professional Development and Career Management.11 However, leaders often find themselves in situations where they are confronting something new. Officers with twenty or more years in the Army have a greater opportunity to have “seen it all,” which is why commanders can command through the lens of their experience, but require staffs to fill in the gaps. After-action reviews are critical tools for individual and organizational learning principally because they afford an opportunity to data-mine lessons from an experience.

Our profession, however, doesn’t operate under any premise that things will ever be optimal. An officer may progress from lieutenant to captain without the experience of maneuvering a platoon in the dark towards an objective as a platoon leader, figuring out logistics and administrative requirements to support a company as an executive officer, or doing penance on a staff in the S-1 (manpower and personnel), S-3, or S-4 (logistics) shops. Likewise, it’s not rare that a major whose company command didn’t include the experience of a decisive action training environment (DATE) rotation will have to perform in just such an environment but at a level of greater responsibility. These staff officers will not, of their own accord, know the appropriate level of detail necessary for a running estimate or a mission analysis brief.

At an organizational level, all things are also not equal. Organizations that haven’t experienced a DATE rotation and don’t have leaders that have experienced a DATE rotation will face a steeper learning curve as they transition from a stability environment. There is no synchronization of maneuver during a stability operation in Afghanistan or Iraq. Stability operation staffs don’t execute MDMP but rely upon targeting instead. MDMP isn’t necessary because maneuver hasn’t been necessary. Units have been assigned an area of operations and do little more maneuver than patrols or company-size raids. Commanders can accomplish the majority of their tasks by commanding through their subordinate commanders and not leveraging their staffs. Staffs are busy in the U.S Central Command area of responsibility, but they’re not under the pressure of a DATE environment. The result is a desultory effect on culture, which is often a network that enables an individual to arrive and gain from peers and noncommissioned officers in the organization. Culture, being the things we do and how we do them, cannot overcome on its own the shift between environments.

For whatever reasons cause a culture like the one depicted in the vignette or depicted in figures 3 and 4 to arise in a formation, the propensity is for leaders, commissioned and noncommissioned officer alike, to emulate modeled behavior. Leaders, informed about the effects of a focus on “achieving” at the expense of the other leader attributes and competencies, can deliberately fashion their strategy for operating in a high pressure, time-constrained environment that demands all the capabilities of the staff.

Conclusion

There are many things we cannot choose whilst in the Army to include the missions we must accomplish or the soldiers, noncommissioned officers, and officers on our team. We do have the choice of how we develop those soldiers, noncommissioned officers, and officers. As Nathalia Crane describes in “The Colors,” “You cannot choose your battlefield, / the gods do that for you, / But you can plant a standard / where a standard never flew.”12 People’s experiences are what they are. We must be cognizant of our individual and organizational weaknesses and then work to address them. Each generation (company grade officers, field grade officers, and commanders) has a role in the organization, and commanders face the dilemma of how to pass along knowledge and enrich the generation who will succeed them. As leaders, they must embrace the fundamentals outlined in doctrine, and the science of MDMP and staff organizations outlined in Field Manual 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations, is a tangible guideline that’s changed little in the last forty years.13 Professionals are not professionals because someone says they are. They’re professionals because they’re experts in their craft. Commanders must drive their subordinates to become experts in the science of their craft. This isn’t simply a task; it must involve the commander directly in developing subordinates. The process is rewarding not only for the subordinate but also for the commander. A prerequisite, obviously, is that the commander must acknowledge there is something for him to learn. Junior staff officers have unique perspectives and are incredibly capable. Worthwhile dialogue with midgrade and senior officers is an opportunity to facilitate the sharpening of cognitive and communicative skills. The investment isn’t only for the individual but for the organization and the Army.

Notes

Steve Leonard, “Broken and Unreadable: Our Unbearable Aversion to Doctrine,” Modern War Institute, 18 May 2017, accessed 25 April 2018, https://mwi.usma.edu/broken-unreadable-unbearable-aversion-doctrine/.

David S. Doyle, “Trends and Observations: Joint Readiness Training Center” (PowerPoint briefing, Fort Polk, LA, 22 February 2018), 3.

Army Doctrine Reference Publication (ADRP) 5-0, The Operations Process (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], May 2012), 2-3.

JRTC Trends, 7 February 2018.

Department of the Army Pamphlet (DA PAM) 600-3, Commissioned Office Professional Development and Career Management (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO), 3 December 2014), 62.

Don Clark, “Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Domains,” Big Dog and Little Dog’s Bowl of Biscuits, accessed 25 April 2018, http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html. Dr. Benjamin Bloom created his taxonomy in 1956 to promote higher forms of thinking in education, such as analyzing and evaluating, rather than just remembering.

Army Doctrine Publication 6-0, Mission Command (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 12 March 2014), 10.

Ibid.

ADRP 5-0, The Operations Process, 1-3.

Field Manual (FM) 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, May 2014), 9-2.

DA PAM 600-3, Commissioned Office Professional Development and Career Management, 10.

Nathalia Crane, “The Colors,” originally published in The Singing Crow and Other Poems (New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1926), http://www.tnellen.com/cybereng/poetry/poems/the_colors.html.

FM 6-0, Commander and Staff Organization and Operations, 2-4–2-29 and 9-1–9-43.

No comments:

Post a Comment