Xi Jinping’s new “Belt and Road” initiative is designed to promote economic development and extend China’s influence. Bloomberg Markets reports on the massive project’s impact along the Silk Road. China is building a very 21st century empire—one where trade and debt lead the way, not armadas and boots on the ground. If President Xi Jinping’s ambitions become a reality, Beijing will cement its position at the center of a new world economic order spanning more than half the globe. Already, China has extended its influence far beyond that of the Tang Dynasty’s golden age more than a millennium ago. The most tangible manifestation of Xi’s designs is the new Silk Road he first proposed in 2013. The enterprise morphed into the “Belt and Road” initiative, a mix of foreign policy, economic strategy, and charm offensive that, nurtured by a torrent of Chinese money, is rebalancing global political and economic alliances.

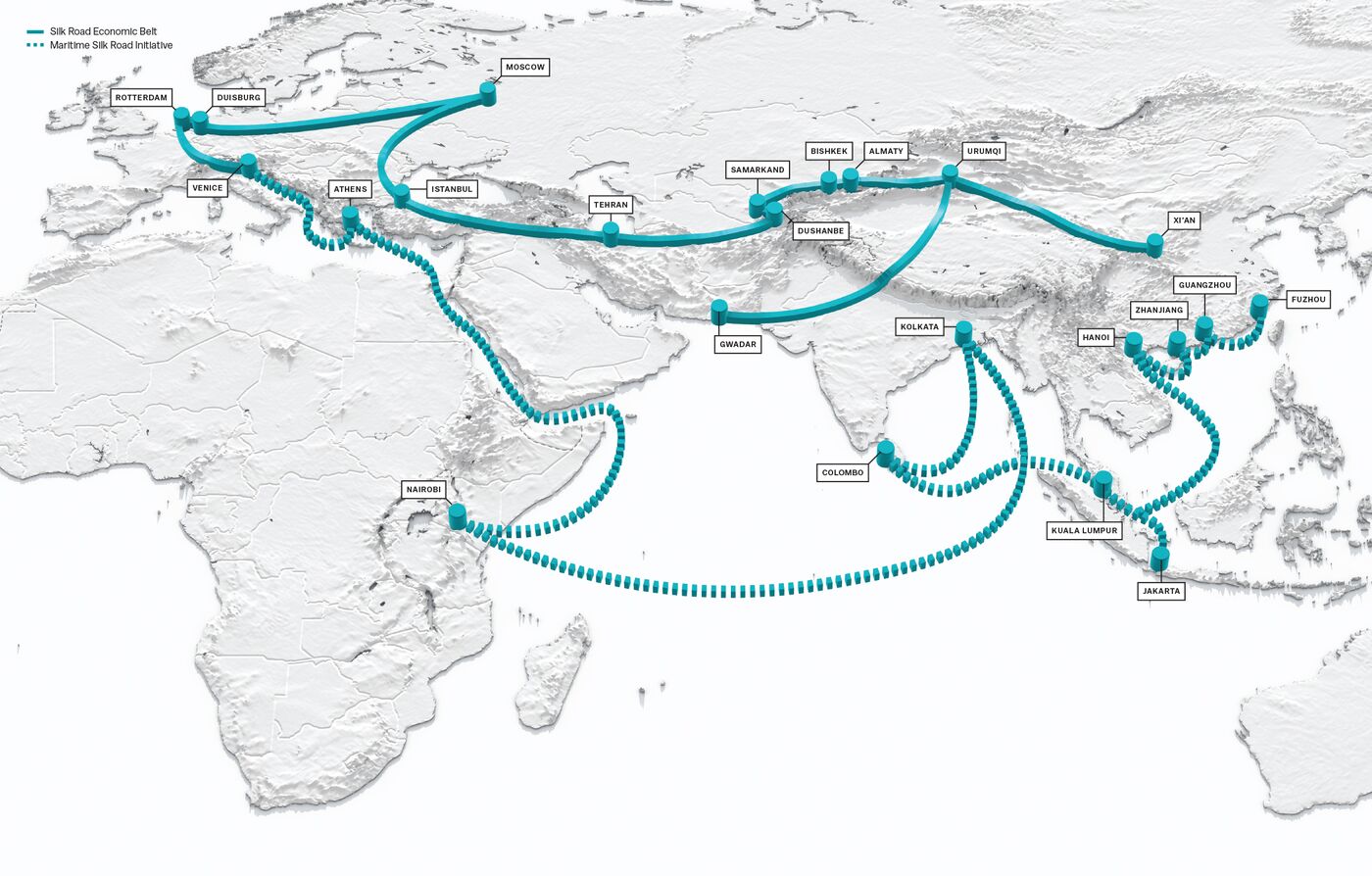

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design for Bloomberg Markets; Sources: Hong Kong Trade Development Council, China's National Development and Reform Commission

Xi calls the grand initiative “a road for peace.” Other world powers such as Japan and the U.S. remain skeptical about its stated aims and even more worried about unspoken ones, especially those hinting at military expansion. To assess the reality of Belt and Road from the ground up, Bloomberg Markets deployed a team of reporters to five cities on three continents at the forefront of China’s grand plan.

What emerges is a picture of mostly poor nations—laggards during the past half-century of global growth—that jumped at the promise of Chinese-financed projects they hoped would help them catch up. And yet as some high-profile ones falter and the cost of their Chinese funding rises, would-be beneficiaries from Hambantota, Sri Lanka, to Piraeus, Greece, are questioning the long-term price. In Malaysia, one of the biggest recipients of Chinese investment in Southeast Asia, newly installed Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad is pushing back. Expressing concerns about loan conditions and the use of Chinese labor that limit benefits to the local economy, he’s put billions of dollars of Chinese-funded rail and pipeline projects on hold.

Xi intends a century-long enterprise. China has already outspent the post-World War II U.S. Marshall Plan, measured in today’s dollars. Within a decade, according to Morgan Stanley estimates, China and its local partners will spend as much as $1.3 trillion on railways, roads, ports, and power grids. “Economic clout is diplomacy by other means,” says Nadège Rolland, Washington-based senior fellow for political and security affairs at the National Bureau of Asian Research. “It’s not for today. It’s for mid-21st century China.”

Belt and Road is very much about politics at home, too. With the government and state-owned enterprises investing vast sums outside China, Xi is encouraging Chinese companies to channel their spending into domestic projects that will directly benefit the economy and, incidentally, the popularity of his regime.

Businesses aren’t exactly defying Xi, but they’ve adjusted their plans to fit his. With the Belt and Road project enshrined in the Communist Party’s constitution as of last year, Chinese companies are using it to help them navigate Xi’s restrictions on foreign investment and capital outflows. Many are sheltering their overseas projects under the umbrella of Xi’s pet project to get the state’s blessing. Belt and Road, says Michael Every, head of financial markets research for Rabobank Group in Hong Kong, is “a political special sauce. ... If you drizzle it on anything, it tastes better.”

At first, the sauce whetted the appetites of many developing countries in Asia and Africa. As the notion of a modern Silk Road gained traction, Belt and Road meandered into places that had never had any connection with ancient caravans. This year it reached South America, the Caribbean, and even the Arctic. In June it rocketed into space: Beijing announced that Belt and Road-participating countries will be among the first in line to plug into China’s new satellite-navigation services.

Most of the proposed plans are infrastructure-based, such as a new deep-sea port in Myanmar and power lines in the Maldives. But almost any overseas investment gets tagged as being part of the initiative: a freight train carrying Chinese sunflower seeds to Tehran, a new courthouse in Papua New Guinea, an irrigation system in the Philippines.

“Economic clout is diplomacy by other means. It’s not for today. It’s for mid-21st century China”

The growing web of trade routes, including the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road Initiative, now extends into at least 76 countries, mostly developing nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, together with a handful of countries on the eastern edge of Europe. With most global trade moving by sea, it’s no surprise that many of the first places to lock up major Chinese investments were ports along with pipelines and other transport links that connect shipping to markets.

China’s plans to build or rebuild dozens of seaports, especially around the Indian Ocean, have sounded alarm bells in Washington and New Delhi: How many of those docks will end up hosting Chinese warships? Just as mighty navies and global networks of military bases helped support trading empires for Britain in the 19th century and the U.S. in the 20th century, so China is building a fleet of submarines, aircraft carriers, and warships that will rival U.S. power.

China has said it has no intention of using Belt and Road to exert undue political or military influence and that the initiative is designed only to enhance economic and cultural understanding between nations. “In pursuing the Belt and Road initiative,” Xi said in 2015, “we should focus on the fundamental issue of development, release the growth potential of various countries, and achieve economic integration.”

If that’s the case, Xi will need to change the perceptions of people who live along the length and breadth of his latter-day Silk Road. And that can only happen in the towns and cities that are being transformed by China’s empire of money. —Adam Majendie, with Sheridan Prasso

Yiwu, China

Nestled in the mountains of Zhejiang province, Yiwu is the embodiment of “Made in China.” The market here is unlike any other. A vast complex of five-story buildings houses 75,000 booths selling 1.8 million kinds of goods across an expanse the size of 650 soccer fields. If you’ve picked up cheap jewelry and toys in District 1, you may need to hop onto a motorcycle taxi to reach auto parts in District 5. Most of those thousands upon thousands of stalls specialize in single items—scissors, for example: scores and scores of different kinds of scissors.

An ancient market town about 180 miles southwest of Shanghai that’s grown into a city of 1.2 million people, Yiwu got a big boost from Belt and Road. People from Beirut to Seoul and beyond have come to start businesses. Some 13,000 traders from around the world now live here. More are arriving every day, says Mohanad Ali Moh’d Shalabi, a Jordanian businessman who owns the Beyti Turkish restaurant in the center of the city and a company that exports goods to the Middle East. “In my restaurant,” he says, “I have met people from countries I have never known of.”

It wasn’t always like this. When Bloomberg reporters visited in early 2014, business was so slow that bored shopkeepers played computer games, read newspapers, or slumped over in their chairs, asleep.

Janey Zhang, whose Zhejiang Xingbao Umbrella Co. employs about 200 workers, remembers the bad old days. In 2013 the vast, labyrinthine halls of Yiwu—a legacy of 1978, when it became one of Communist China’s first wholesale markets—were almost deserted. Wholesalers and producers struggled with soaring manufacturing costs and the rise of online marketplaces such as Alibaba.

Then came a glimmer of hope. On social media and television, Zhang started seeing reports about a new freight train that would roll west for thousands of miles, crossing China into Central Asia and on into Europe. This was part of the Xi government’s “New Eurasian Land Bridge,” a seemingly endless skein of stacked container wagons replicating ancient Silk Road camel caravans. “The impact of the railway was huge,” Zhang says. “I remember seeing pictures of it piled high with cargo. After the service started, our sales and customers quickly increased.”

The first Europe-bound train pulled out of here in November 2014, heading to Kazakhstan and Russia, then through Eastern Europe and on to Madrid—an 8,000-mile journey that supplanted the Trans-Siberian Railway as the world’s longest freight-train route. Since then, more routes have opened to destinations including London, Amsterdam, and Tehran.

Zhang’s dream is for her Real Star brand to become the Hermès of umbrellas. Europe has long been her biggest market. Since the new freight trains came to Yiwu, she’s picked up customers all along the route, from Kazakhstan to Russia to Iran.

Trains have cut the time to Europe by a third or more compared with ships. The return journeys bring European goods such as wine, olive oil, vitamin pills, and whiskey. China Railway Express Co. said the value of outbound freight from Yiwu in the first four months of 2018 jumped 79 percent from a year earlier, to 1.8 billion yuan ($268 million), while imports tripled to 470 million yuan.

Even so, rail freight accounts for less than 1 percent of China’s overall exports. While it can shorten journey times to Europe, it’s more expensive than seaborne trade and slower and less flexible than air cargo. But for cities such as Yiwu, and especially for those in western China even farther away from seaports, the train that Xi built has injected new life into their economies. —Kevin Hamlin and Miao Han

Hambantota, Sri Lanka

In a southern Sri Lankan jungle, Dharmasena Hettiarchchi plucks green chile peppers that grow in the shade of banana trees. His grandfather tended the same patch of land when this island was the British colony of Ceylon. Hettiarchchi takes a break from the heat under a teak tree, removes his wide-brimmed hat, and says, “If a jeep with Chinese characters comes down the road, the whole village will gather in protest.”

Hettiarchchi’s village and the surrounding town of Hambantota have become a cautionary tale for Xi’s Belt and Road aspirations. The idea was to take an inconsequential harbor visited by fewer than one ship a month on average and turn it into a modern, bustling seaport adorning a southern Belt and Road maritime route. It hasn’t turned out so well.

After Sri Lanka elected Hambantota native Mahinda Rajapaksa as president in 2005, he began sprinkling development projects across the region, one of the least-developed parts of this nation of 21 million people. Even long before Belt and Road was officially embedded in Chinese government policy, Beijing was eager to lend a hand, and Chinese loans financed Rajapaksa’s munificence. Hambantota (population at the time 11,200) got a new port, an international conference center, a cricket stadium, and an airport that, despite all the staff on show, doesn’t service a single scheduled flight.

To fund the projects here and others all across Sri Lanka, the Rajapaksa government fell deep into debt. The port at Hambantota, for example, was partly funded during the Rajapaksa administration by a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China. By the time Rajapaksa was voted out of office in 2015, more than 90 percent of Sri Lanka’s government revenue was going toward servicing debt.

Last year, with Xi’s Belt and Road plan in full flow, a new Sri Lankan government moved to ease the debt. In return for $1.1 billion, it basically handed the seaport over to China. Under a 99-year lease agreement, the government gave 70 percent ownership of the port to China Merchants Group, a state-owned company with revenue bigger than Sri Lanka’s economy.

China Merchants has promised to revive the port and turn it into a major regional trading hub. But some local people have had enough of promises. “All these huge projects are a waste,” says Sisira Kumara Wahalathanthri, a local politician who opposes the current Sri Lanka government. “No ships are coming to the port. No flights are coming to the airport.”

After 30 years of civil war, many Sri Lankans are glad to see investment, any investment. At the port and in a surrounding industrial zone, construction work continues, presaging change. Displaced from their normal habitats, wild elephants regularly trample the port’s perimeter fence. At a nearby ancient Buddhist temple, head monk Beragama Wimala Buddhi Thero says he began attending protests because the area’s way of life is under threat. While his temple will be spared, the nearby farms won’t, leaving him and his fellow saffron-robed monks without worshipers.

“It’s becoming a Chinese colony,” he says of Hambantota. In a darkened hall, reclining on a wooden throne decorated with elaborately carved lions and flowers, he complains that China has already despoiled its own rivers in the name of progress. “If that kind of pollution comes here,” he says, “it doesn’t matter if we’re developed.”

The chile farmer Hettiarchchi is wary of the surveyors who’ve begun to appear in his neighborhood, making measurements and leaving their telltale markers behind. He says the plan is for him to be relocated to a part of eastern Sri Lanka to make way for development. It’s all happening so fast, and what Hettiarchchi could be losing can’t be replaced easily or quickly. Gesturing to the towering teak above him, the 52-year-old says, “A tree like this cannot grow within my lifetime.” —Iain Marlow, with Sheridan Prasso

Gwadar, Pakistan

Surrounded by desert in southwest Pakistan there’s a stone arch bearing a single name, Al-Noor. Farther along a desolate road, a black shipping container has been painted to tell you where you are: Gwadar Creek Arena.

Al-Noor and Gwadar Creek are planned housing developments—emphasis on “planned.” There’s nothing here yet. The same goes for White Pearl City, Canadian City, Sun Silver City, and other residential tracts on the drawing boards. What you see are billboards, lots of them, as speculators and developers carve out future projects on the sun-blasted outskirts of an old fishing village named Gwadar.

Gwadar is a city of dreams made in China. Beijing is pouring money into highways and roads, a hospital, a coal-fired power plant, a new airport, a special economic zone along the lines of Shenzhen, and, crucially, the port. The chain of events that led to Chinese involvement here fits a pattern repeated up and down Belt and Road routes: Local or national efforts to expand a port stumble; China comes in and saves the day.

In the case of Gwadar, a redevelopment project begun in the 2000s under then-military ruler Pervez Musharraf foundered. In 2013 the Chinese arrived. A deep-water port here would be a natural southern terminus for a key binational project started that year, the $60 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, as well as an important component of Belt and Road. To that end, Beijing is financing the lion’s share of the $1 billion in spending on the port and infrastructure development elsewhere in Gwadar.

Gwadar, across the Arabian Sea from Oman, is so remote that its electricity comes from Iran, 60 miles down the coast. In recent years, the village has become a city of 100,000 or so. Although still mostly a gigantic building site flanked by highways and crisscrossed by roads, signs of change abound.

Ghulam Hussain, 40, is a shopkeeper. Every month, he gets six to eight truckloads of rice, flour, sugar, and other groceries delivered to him from Karachi, an eight-hour drive to the east. Five years ago, three loads a month met his needs. “There was nothing in Gwadar before,” he says. “It was deserted. We were really backward. Since the Chinese came, our businesses are booming.”

Even so, it’s hard to imagine Gwadar as the sea terminus of a road-and-rail trade link stretching 3,000 miles to eastern China. Most of the route would traverse some of the world’s most inhospitable—and economically barren—mountains and deserts.

A rail line, says Andrew Small, a senior transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a Washington-based public-policy think tank, “makes no economic sense in the foreseeable future. The economy of Pakistan and the economy of western China would need to look quite different.”

Some say that military expansion is the real driver of the activity in and around Gwadar. “The Gwadar Port shows that there is a close link to the Chinese military ambitions,” U.S. Congressman Ted Yoho (R-Fla.) said during Foreign Affairs Committee hearings on U.S.-Pakistan relations in February.

Zahid Ali, who used to run a small business topping up credit on mobile phones in Sindh province in eastern Pakistan, sees things very differently. Desperate to find a way to pay off 800,000 rupees ($6,300) in debts, he asked a client if there was any job in Pakistan that paid 50,000 rupees a month. Go to Gwadar, the customer replied.

That’s what Ali did. He started as a laborer, learned steel work, and was soon earning 55,000 rupees a month. Now, having learned a little Chinese, he’s been promoted to supervisor. “We’re getting good money, so people are coming from far away,” he says during his work shift on the six-lane East Bay Expressway. “It’s good that the Chinese came here. A lot of people have gotten jobs who were jobless.”

The Chinese who came here to work don’t mix much with the locals. Some of the 150 or so of them live in a guarded and gated compound where green shipping containers have been converted into living spaces.

One of the first things a visitor to Gwadar notes is that there are more soldiers on the streets than police—an added precaution against the threat of terrorism across Pakistan. Security is tight because Chinese wouldn’t come otherwise, says a Pakistani army officer who declined to be named because he’s not authorized to talk to the news media. He says there are checkpoints on all the roads leading into the city.

Good, says Naseem Ahmed, 25, who works for the provincial government. “Security is great here,” he says as he warms up before taking part in a soccer game at a local stadium. “You can be out at 3 a.m. in the morning, and there is no fear.” —Faseeh Mangi, with Chris Kay

Mombasa, Kenya

Astride his boda boda, or motorcycle taxi, at a crossroads in Mombasa, Simon Agina is counting containers on a passing train that’s heading to Nairobi: “… 82, 83, 84.”

There are plenty of freight containers back where those came from—and much more besides. The port of Mombasa, Kenya’s import lifeline, is a heaving mass of traffic of all sorts. Trucks line up quayside to move shipping containers from the docks to the railway. Three-wheeled tuk-tuks weave dangerously between other vehicles through hot, dusty streets filled with noise and litter.

Kenya’s largest port is also its oldest. So in 2011, with the ancient British colonial-era Mombasa-to-Nairobi narrow-gauge railway falling into disrepair and Beijing in the market for African investments, Kenya made its move. It agreed to let China finance and build a standard-gauge railway at a cost of $3.8 billion. The Mombasa-Nairobi SGR, as it’s called, is the nation’s largest infrastructure project since independence from Britain in 1963.

Atanas Maina, managing director of Kenya Railways, says more than 30,000 Kenyans were employed directly on the project, which was run by China Road and Bridge Corp.; an additional 8,000 worked for subcontractors.

The first paying passengers rode the line in June last year. Along its 293-mile journey, the SGR rumbles across almost 100 bridges and viaducts, many designed to allow the lions, zebras, and other wildlife that inhabit two national parks, Tsavo East and Tsavo West, to cross under the tracks.

Freight trains like the one Agina saw from his boda boda began running in January. “Those are 84 trucks off the road,” he says as the containers whiz by. The railway cuts the Mombasa-Nairobi trip to five hours, down from more than eight by truck. Five freight trains a day were making the journey during spring. The number could eventually increase to 12, removing as many as 1,700 of the 3,000 trucks that currently ply the route.

Like any major infrastructure project, the rail line has its detractors. The economist and government critic David Ndii says it’s not commercially viable, while a Kenyan newspaper, the Standard, accused China Road and Bridge of “neo-colonialism, racism and blatant discrimination” in its treatment of local employees; Kenya Railways subsequently said it would investigate the allegations.

Environmental activists tried without success to block the SGR from going through Tsavo parkland and have taken legal action to try to stop the next phase of railway construction, which would run the line through Nairobi National Park on the edge of the capital.

Trucking companies, whose business grew steadily as the old railway decayed, are now worried about the loss of customers. Vanessa Evans, managing director of Rongai Workshop & Transport Ltd., says the SGR could have been a plus for the Kenyan economy in the long run, but poor coordination at the Mombasa and Nairobi rail terminals causes cargo backups and delays. The new rail line, she says, “has nearly destroyed our business because the turnaround time varies between not good and awful. We have been in agony for the past five months.”

The train that pulls out of Nairobi Railway Station each morning at 8 o’clock, with noteworthy punctuality, is called the Madaraka Express. In Swahili, “madaraka” means power or responsibility; Madaraka Day, a national holiday, celebrates self-rule. If the old railway was a relic of Kenya’s British colonial past, the new one, built with Beijing’s money, could be seen as a harbinger of a new kind of imperial reach.

It’s a blue-suited Chinese instructor who makes sure the female train attendants—uniformed in the colors of the Kenyan flag—are standing in a nice straight line as passengers board. China financed 90 percent of the SGR’s $3.8 billion cost. And the giant Chinese Communications Construction Co. will operate the rail line for its first decade.

The area around the station thrums with activity as construction pushes ahead on houses, container yards, and warehouses. Along the route to Mombasa, gleaming steel-and-glass stations stand out against clusters of tiny houses with rusty corrugated iron roofs and mud walls; the contrast encourages the locals “to dream big,” says Maina.

Michael Ndungu, 21, a student who studies in Mombasa and visits the capital on weekends, used to take the bus. “The SGR has made my life much better,” he says. “It is faster and definitely safer.” In Mombasa the surge in passengers—1.3 million during the first six months of the year—has been good for the economy. “Business is good,” says Stephen Kazungu, a 26-year-old taxi driver.

The newly laid track, the trains, the stations—“You don’t see that kind of infrastructure development in this part of the country,” says Agina, the 22-year-old boda boda driver, as the freight train fades into the distance. “This is amazing.” —Samuel Gebre

Piraeus, Greece

It was the spring of 2016. Greece was in the vise-grip of the European sovereign debt crisis. Its neighbors and creditors were pressuring the government to enforce austerity. So Greece sold control of Piraeus, the storied seaport once connected to Athens by fortified walls, to China Cosco Shipping Corp., a Chinese state-owned enterprise.

The deal bears many of the hallmarks of China’s biggest Belt and Road projects. It began years before Xi’s signature project was announced—in 2009, Cosco won a contract to run part of Piraeus’s container business—and was then handily folded into the initiative; it was geared largely toward enhancing the reach of China’s maritime trade; and it involved a host nation desperate for investment.

But unlike many of China’s high-priced Belt and Road investments, this isn’t a remote greenfield construction project in a developing nation. The port deal marked China’s gradual takeover of one of Europe’s oldest and most important sea gateways. Piraeus has been Athens’s port and shipyard for about 2,500 years, a perch on the Mediterranean that helped Athens become a naval superpower.

From his office, Ioannis Kordatos, managing director of the Hellenic Welding Association, can see the wall of containers stacked high at Pier II, Cosco’s original beachhead here. “If Cosco magically disappeared tomorrow, it would be a huge loss,” says Kordatos. “What matters isn’t that they are Chinese but that they are a private company doing serious business in the area.”

Very serious business. The 2016 deal gave Cosco a 67 percent share of Piraeus Port Authority SA for €368.5 million ($429.5 million). During PPA’s first full year under Chinese control, its net income jumped 69 percent, to €11.3 million, as revenue from its container terminal rose 53 percent. Since Cosco first became involved, Piraeus has risen to be Europe’s seventh-busiest container port; 10 years ago, it wasn’t in Europe’s top 15.

Piraeus is a bustling city in its own right. Marinas here are filled with Athenians’ yachts ready for weekend sailing. Passenger ferries dock near the town center to carry locals and tourists to Aegean islands. Farther west, in the repair yards, workers mend boats. Above all, giant gantry cranes loom over shipping containers.

These days, whether you arrive here by sea, by metro, or by road, you’re bound to run into construction, with chunks of the city boarded up as bulldozers work on a new subway station and public transportation connections.

In the heart of Piraeus, Cosco plans to upgrade the ferry and cruise ship terminals, adding a shopping mall and new hotels. Farther out, around the Gulf of Elefsina, Cosco’s investments could help revive Greece’s rust-belt industrial heartland in the Thriasio Plain west of Athens. There, a planned logistics center, linked to the port by rail, could become a staging area for goods headed north through the Balkans.

Not everybody in Piraeus shares Kordatos’s warm feeling toward Cosco’s purchase of PPA. “If I had the money, I’d buy it myself rather than let it go to foreigners,” says Evlampia Kavvatha, who owns a store selling shelving in the town center.

Perhaps Cosco’s presence here is a case of desperate times calling for desperate measures. Like the rest of the country, Piraeus has been hit by a depression that’s wiped out a quarter of the nation’s economic output since the sovereign debt crisis. Away from the main shopping district street, Piraeus suffers from the blight of empty storefronts that afflicts cities across Greece.

Giorgos Gogos, general secretary of the Piraeus Dockworkers Union, says he’s worried about the impact of a Chinese state-owned enterprise on labor relations and the local community. “We think it’s a mistake for infrastructure like this to leave the state,” he says. “The Chinese have their own way of operating. [Cosco is] a state colossus backed by capital of the Chinese state. It has the characteristic of Chinese state capitalism.”

For all the concern about the potentially corrosive effects on Greece’s economy and sovereignty—and about Beijing’s ulterior motives—Cosco’s incursion into Piraeus has something in common with other investments by Beijing along the vast and meandering Belt and Road: China put its money where others wouldn’t. —Marcus Bensasson

Majendie is a senior editor in Singapore. Hamlin and Han cover the economy in Beijing. Marlow covers government in New Delhi. Mangi covers companies in Karachi. Gebre covers news in Nairobi. Bensasson covers the economy in Athens.

No comments:

Post a Comment