Nick Van Mead

As their hand-built wooden dhow approaches the shore, Ibrahim Chamume and his fellow fishermen take in the sail and prepare to sell their catch to the small huddle of villagers waiting on the white sand. He has been making a living like this on the Indian Ocean since he was 14. His father was a fisherman, too. Now in his 30s, Ibrahim says earning enough from traditional fishing is tough, but has its compensations. There is the view across the tranquil lagoon to the mangrove swamps; the unspoiled beaches and bays; the lush vegetation and smallholdings growing maize, cassava, cashews and mango. Such scenes must have played out in the tiny Tanzanian village of Mlingotini for centuries.

As their hand-built wooden dhow approaches the shore, Ibrahim Chamume and his fellow fishermen take in the sail and prepare to sell their catch to the small huddle of villagers waiting on the white sand. He has been making a living like this on the Indian Ocean since he was 14. His father was a fisherman, too. Now in his 30s, Ibrahim says earning enough from traditional fishing is tough, but has its compensations. There is the view across the tranquil lagoon to the mangrove swamps; the unspoiled beaches and bays; the lush vegetation and smallholdings growing maize, cassava, cashews and mango. Such scenes must have played out in the tiny Tanzanian village of Mlingotini for centuries.

Bagamoyo, if the project goes ahead as planned, will be transformed into the largest port in Africa. That is looking ever more likely: after years of delay, the Tanzanian government says it is in the final stages of talks with state-run China Merchants Holdings International.

Bagamoyo, if the project goes ahead as planned, will be transformed into the largest port in Africa. That is looking ever more likely: after years of delay, the Tanzanian government says it is in the final stages of talks with state-run China Merchants Holdings International.

Meanwhile, landlocked Ethiopia got a 470-mile electric railway from its capital, Addis Ababa, to the port in the neighbouring dictatorship of Djibouti. The £2.5bn project – financed by a Chinese bank and built by Chinese companies – opened in January. Addis’s new light rail system, too, was funded and built by China, and operated by Shenzhen Metro Group. And Djibouti, in exchange for major investments, preferential loans, a pipeline and two airports, got China’s first overseas military base.

Meanwhile, landlocked Ethiopia got a 470-mile electric railway from its capital, Addis Ababa, to the port in the neighbouring dictatorship of Djibouti. The £2.5bn project – financed by a Chinese bank and built by Chinese companies – opened in January. Addis’s new light rail system, too, was funded and built by China, and operated by Shenzhen Metro Group. And Djibouti, in exchange for major investments, preferential loans, a pipeline and two airports, got China’s first overseas military base.

Many African people certainly see grounds for optimism. Almost two-thirds of Tanzanians view China favourably, compared with less than half of Europeans and Americans, according to the

As their hand-built wooden dhow approaches the shore, Ibrahim Chamume and his fellow fishermen take in the sail and prepare to sell their catch to the small huddle of villagers waiting on the white sand. He has been making a living like this on the Indian Ocean since he was 14. His father was a fisherman, too. Now in his 30s, Ibrahim says earning enough from traditional fishing is tough, but has its compensations. There is the view across the tranquil lagoon to the mangrove swamps; the unspoiled beaches and bays; the lush vegetation and smallholdings growing maize, cassava, cashews and mango. Such scenes must have played out in the tiny Tanzanian village of Mlingotini for centuries.

As their hand-built wooden dhow approaches the shore, Ibrahim Chamume and his fellow fishermen take in the sail and prepare to sell their catch to the small huddle of villagers waiting on the white sand. He has been making a living like this on the Indian Ocean since he was 14. His father was a fisherman, too. Now in his 30s, Ibrahim says earning enough from traditional fishing is tough, but has its compensations. There is the view across the tranquil lagoon to the mangrove swamps; the unspoiled beaches and bays; the lush vegetation and smallholdings growing maize, cassava, cashews and mango. Such scenes must have played out in the tiny Tanzanian village of Mlingotini for centuries.

Cities of the New Silk Road: what is China's Belt and Road project? Show

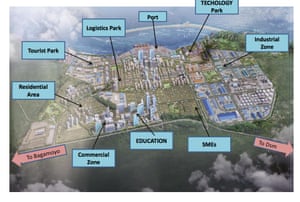

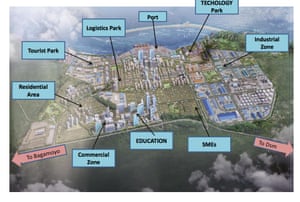

In a decade, however, the mud-and-thatch homes of Mlingotini, and a further four villages along this coastline 30 miles north of Dar Es Salaam, will be gone – razed to make space for a $10bn Chinese-built mega-port and a special economic zone backed by an Omani sovereign wealth fund.

The area south of Bagamoyo – once notorious as a key staging point in the slave trade and unsuccessfully proposed 12 years ago as a world heritage site– is seen by China as a new Shenzhen. Before Deng Xiaoping designated Shenzhen as China’s first special economic zone in 1979, it, too, was just a small fishing town. Now it is a hi-tech hub and one of the world’s biggest cities.

Bagamoyo, if the project goes ahead as planned, will be transformed into the largest port in Africa. That is looking ever more likely: after years of delay, the Tanzanian government says it is in the final stages of talks with state-run China Merchants Holdings International.

Bagamoyo, if the project goes ahead as planned, will be transformed into the largest port in Africa. That is looking ever more likely: after years of delay, the Tanzanian government says it is in the final stages of talks with state-run China Merchants Holdings International.

The lagoon will be dredged, to allow access to the vast cargo ships that will queue many miles out to sea. As for the special economic zone, the original masterplan shows factories in a fenced-off industrial area, and apartment blocks to accommodate the estimated future population of 75,000. There is even talk of an international airport. Many of the villagers have already accepted compensation for the loss of their homes.

The comparison with Shenzhen may not be so far-fetched, says the China-Africa specialist Lauren Johnston of New South Economics. “Would visitors to Shenzhen in 1980 have believed what would be unlocked by that sleepy port?” she says. “Bagamoyo could become an industrial gateway not only for youth-filled Tanzania but half a dozen landlocked African countries. There are parallels.”

The proposed radical transformation of the Bagamoyo coastline is an unofficial extension to east Africa as part of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative – and is just the latest in a long line of China-in-Africa projects. Ahead of next month’s China-Africa summit, foreign minister Wang Yi is inviting African leaders to “get on board the fast train of development”.

The Cityscape: get the best of Guardian Cities delivered to you every week, with just-released data, features and on-the-ground reports from all over the world

It is now nine years since China overtook the US as Africa’s largest trading partner. Although Kenya and Ethiopia were the only two African nations among the 30 countries signing economic and trade agreements at the Belt and Road Forum (Barf) in Beijing in May last year, China has been busy on the continent.

The flagship Belt and Road project is Kenya’s 290-mile railway from the capital, Nairobi, to the port city of Mombasa, which opened to the public last year. There are plans to extend that network into South Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi; it was already the country’s largest infrastructure project since independence.

Meanwhile, landlocked Ethiopia got a 470-mile electric railway from its capital, Addis Ababa, to the port in the neighbouring dictatorship of Djibouti. The £2.5bn project – financed by a Chinese bank and built by Chinese companies – opened in January. Addis’s new light rail system, too, was funded and built by China, and operated by Shenzhen Metro Group. And Djibouti, in exchange for major investments, preferential loans, a pipeline and two airports, got China’s first overseas military base.

Meanwhile, landlocked Ethiopia got a 470-mile electric railway from its capital, Addis Ababa, to the port in the neighbouring dictatorship of Djibouti. The £2.5bn project – financed by a Chinese bank and built by Chinese companies – opened in January. Addis’s new light rail system, too, was funded and built by China, and operated by Shenzhen Metro Group. And Djibouti, in exchange for major investments, preferential loans, a pipeline and two airports, got China’s first overseas military base.

While east Africa has been the main focus of Belt and Road on the continent, Chinese infrastructure projects stretch all the way to Angola and Nigeria, with ports planned along the coast from Dakar to Libreville and Lagos. Beijing has also signalled its support for the African Union’s proposal of a pan-African high-speed rail network.

Where does China in Africa end, and Belt and Road begin? Professor Steve Tsang, director of the Soas China Institute, says the definition is vague – but getting too caught up in that misses the point. “If you’d like a project to be Belt and Road, it can be Belt and Road,” he says. “You can fit anything into it. It’s a way of getting support for your project.”

The new port of Bagamoyo could see the revival of what Tsang calls “the very first China in Africa mega-project”: the Tazara railway line, stretching from the copper mines of Zambia to Dar Es Salaam.

Tazara dates back to the 1960s, when Chairman Mao Zedong won friends on the continent by supporting anti-colonial movements such as that of Julius Nyerere in Tanzania. The 1,100-mile railway opened to much fanfare in 1976 – it was the first infrastructure project conceived on a pan-African scale.

Four decades later, the once-grand station in Dar Es Salaam stands empty most days, its missing ceiling panels exposing rotting beams and allowing water to pool on the floor. Two rusty trains a week rattle up and down the line. In the cavernous main hall, a few people wait under broken TV screens for an express service which is running nine hours late.

But the old line could “shine again”, promised former Chinese ambassador Lu Youqing. There is a proposed extension to Bagamoyo, and a plan to link a revamped Tazara to landlocked Malawi, Rwanda, and Burundi. The railway’s chief executive has talked excitedly of 125mph trains.

The key difference is that Tazara was mostly paid for by Chinese aid money – a significant investment given how impoverished China was at the time. Whether branded Belt and Road or not, virtually every new project is now funded by Chinese commercial loans.

There have been concerns about these loans. Research by the Centre for Global Development found Djibouti was among eight Belt and Road countries significantly or highly vulnerable to debt distress from the loans – with IMF figures showing its public external debt swelling from 50% to 85% of GDP in two years. Before his visit to Africa in March, former US secretary of state Rex Tillerson accused China of predatory loan practices; when she was secretary of state, Hillary Clinton warned of China’s “new colonialism”. Four months into the job, Tillerson’s successor Mike Pompeo is yet to visit.

Though China loaned a whopping $95.5bn on the continent between 2000 and 2015, researchers at the China Africa Research Initiative found most of this was spent addressing Africa’s infrastructure gap. Some 40% of the Chinese loans paid for power projects, and another 30% went on modernising transport infrastructure. The loans were at comparatively low interest rates and with long repayment periods.

“The risk for African borrowers relates to the project’s profitability,” says Cari director Deborah Bräutigam. “Will they be able to generate enough economic activity through these projects to repay these loans? Or are the projects seen more as ribbon-cutting opportunities? The Chinese believe that ports and special economic zones are a ‘win-win’ development tool. It’s what they did at home at an earlier stage of their development.”

Many African people certainly see grounds for optimism. Almost two-thirds of Tanzanians view China favourably, compared with less than half of Europeans and Americans, according to the

As Bagamoyo readies for a seismic transformation from sleepy town to mega-port, the residents seem to feel unanimously positive. From the taxi drivers in the old town in their starched white kanzu cotton robes to the fashionable young restaurant manager, all were confident they would profit from more businesses, more offices, more jobs, more money. The original masterplanincludes talk of schools and health centres, playgrounds and fibre-optic broadband.

Even the fishermen – whose quiet lives look set to be turned upside down – seem optimistic. Despite concerns that the compensation already paid in connection with the special economic zone was not enough to relocate, most thought the new wealth would somehow trickle down. “It will bring many benefits,” says Ibrahim Chamume as we shelter under a thatched roof from a tropical downpour. His first child died young but he and his wife hope to have more. “Even if I do not prosper, they will.”

No comments:

Post a Comment