By Pawel Zerka for European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

How willing is the EU to regard its neighboring regions as within its sphere of influence? To help provide an answer, Pawl Zerka explores the attitudes of EU member states towards the Union’s involvement as a security provider in the Western Balkans, eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia. He also highlights how these attitudes show that the EU’s overall security priorities very much align with those of Germany’s current government. This article was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) on 10 August 2018. The security perceptions scorecard highlights the EU's ability and willingness to act as a security provider, depending on the region

How willing is the EU to regard its neighboring regions as within its sphere of influence? To help provide an answer, Pawl Zerka explores the attitudes of EU member states towards the Union’s involvement as a security provider in the Western Balkans, eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia. He also highlights how these attitudes show that the EU’s overall security priorities very much align with those of Germany’s current government. This article was originally published by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) on 10 August 2018. The security perceptions scorecard highlights the EU's ability and willingness to act as a security provider, depending on the region

Europeans may have begun to lose their long-held aversion to what German Chancellor Angela Merkel calls “old thinking about spheres of influence”. Borne out of their twentieth century experiences (as Kadri Liik argues in ECFR’s latest EU-Russia Power Audit), EU member states’ traditional mindset appears to be giving way amid an ongoing migration crisis and a resurgence in great-power politics in their neighbourhood.

The crisis laid bare the consequences for Europe of instability and underdevelopment in Africa and the Middle East, underlining the European Union’s failure to consistently pay attention to these regions. Combined with growing geopolitical competition – seen in Russian and Chinese activity in the Western Balkans, which US disengagement from the region partly enables – this seems to have forced European countries to reassess their outlook.

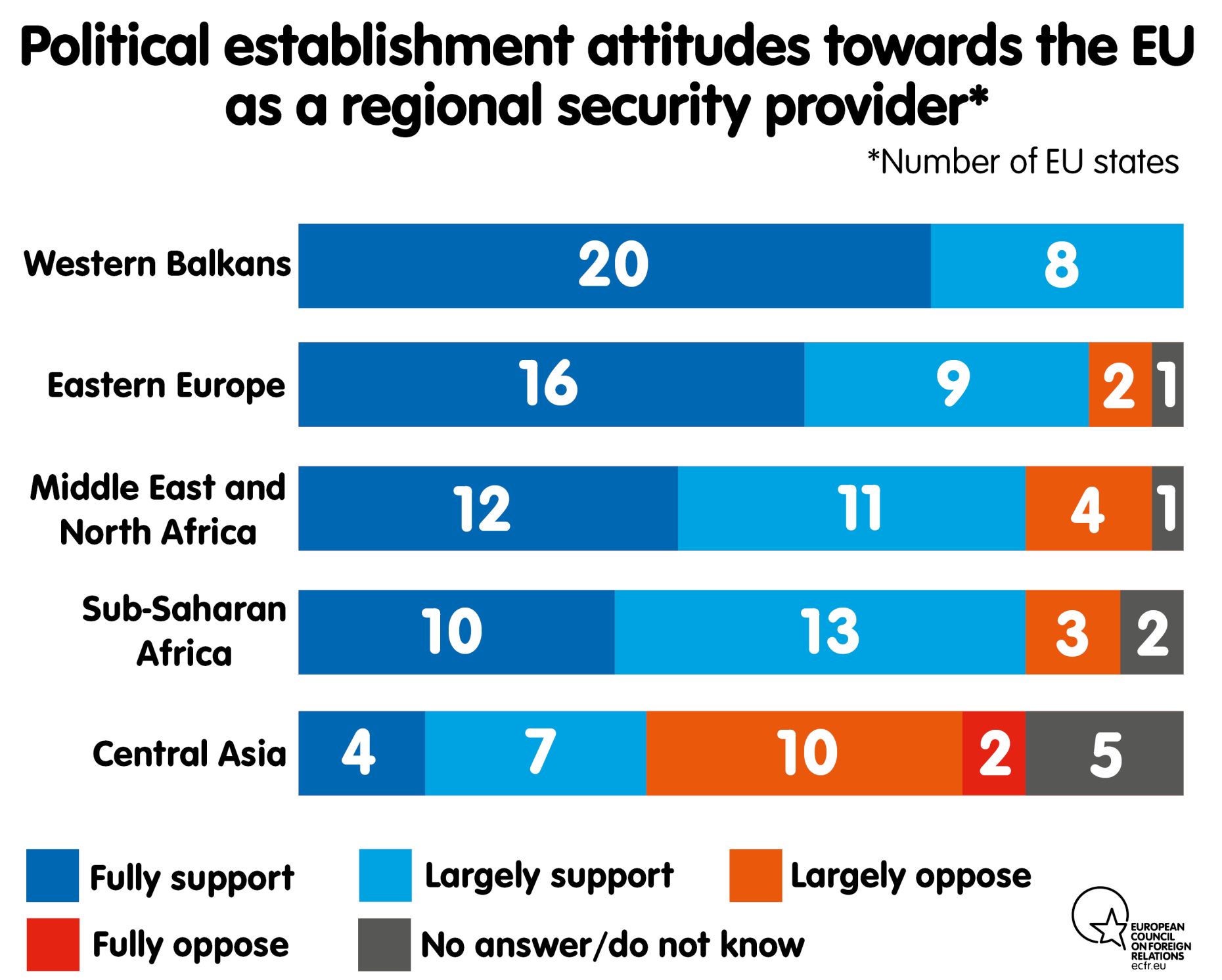

The EU’s willingness to act as a security provider in neighbouring regions may indicate whether it regards them as being within its sphere of influence. This is one of several issues ECFR examines in its new security perceptions scorecard, covering all 28 EU member states (see diagram below).

As the scorecard shows, member states unanimously support active EU involvement in the western Balkans. Several western Balkans countries are working towards EU membership, while the EU has close economic links with the region, as its most important trade partner, foreign investor, and foreign donor by far. As a result, any rise in Russian or Chinese involvement in the western Balkans, as well as any increase in tension between states in the region, causes alarm in the EU. Nonetheless, there is an ongoing debate within the Union over whether the EU accession process is the best tool for promoting democratic and economic reform in the western Balkans.

According to ECFR’s survey, most member states strongly support active EU involvement in eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Although the EU is somewhat divided between countries focused on the east and those more interested in the south, there is considerable overlap between the two groups.

Only Portugal and Italy would rather the EU was not actively involved in eastern Europe. But Greece, Cyprus, and Hungary do not share this view, even if – as the scorecard demonstrates – they also regard Russia as posing no threat to their security. Italy’s focus on Africa (rather than eastern Europe) is understandable due to the strong links between instability in the Sahel and migration flows, the country’s key security concern.

The Netherlands, Latvia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Malta have not vocally supported the EU’s active involvement in sub-Saharan Africa – despite a growing awareness within the Union that stability in the region is important to European security. The Netherlands’ foreign and security policy documents focus on Europe’s eastern neighbourhood for crisis management operations (although they cover a wider area for development aid). Meanwhile, Romania is mainly concerned about the western Balkans and the Black Sea region, feeling relatively insulated from the EU’s migration challenges.

EU member states have comparatively little interest in Central Asia: only Poland, the UK, Finland, and Slovakia strongly believe that the EU should be actively involved in the region, while another seven countries moderately support such involvement. In contrast, 12 countries (including France and Germany) oppose active EU involvement in the region. Altogether, the EU seems to concentrate on the western Balkans, the Middle East, and Africa, at the expense of Central Asia (and more distant regions).

Interestingly, the EU’s overall security priorities very much align with those of the current government in Berlin. Most German leaders believe that the EU should not pursue global ambitions but rather invest in the stability of its neighbourhood, especially areas in which Germany and the Union have substantive security interests or need to protect trade routes and supply chains. This is why they see eastern Europe and the western Balkans – along with (partly due to migration flows) the Middle East and Africa – as crucial to European security. Indeed, according to its coalition treaty, the German government will seek an increase in funding for cooperation with Africa in the next EU budget. Similarly, Berlin views Central Asia as comparatively unimportant (even though it directs some development aid towards the region).

The next Multiannual Financial Framework – which will shape EU budgets for years to come – will likely reflect the EU’s perceptions of which regions fall within its sphere of influence, focusing particularly on Africa and the western Balkans. Nonetheless, it remains to be seen whether an apparent convergence around the German vision of priority regions will shift the EU’s strategic focus onto these areas – especially at a moment when, following the refugee crisis, new challenges to Berlin’s leadership in Europe are emerging.

About the Author

Pawel Zerka is the cordinator of the ECFR's European Power program.

No comments:

Post a Comment