IF A war were to break out in Europe, its early stages might look something like NATO’s recent exercise on the Letzlinger Heath, some 100km (60 miles) west of Berlin. The war game imagined an enemy (Russia, say) sweeping across the northern European plain and into a NATO member state (Estonia, say). In the front line of resistance was NATO’s new Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF), whose rotating leadership will pass to the Bundeswehr, Germany’s armed forces, next year. The scenario was earnestly rehearsed by an array of allied forces whose common language was English. A commander’s voice crackled over the radio, ordering troops to retake the town of Schnöggersburg and its airport. The air grew thick with dust and cordite as Leopard 2 tanks raced across the scrubby landscape, with howitzer fire providing cover and helicopters circling overhead. Fire-fights broke out across the rooftops, then Norwegian tanks rolled through the cleared streets and on to the airport. “I have spent 30 weeks in training with my troops and I can tell you: we will fulfil our mission,” affirmed Brigadier-General Ullrich Spannuth with evident pride.

IF A war were to break out in Europe, its early stages might look something like NATO’s recent exercise on the Letzlinger Heath, some 100km (60 miles) west of Berlin. The war game imagined an enemy (Russia, say) sweeping across the northern European plain and into a NATO member state (Estonia, say). In the front line of resistance was NATO’s new Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF), whose rotating leadership will pass to the Bundeswehr, Germany’s armed forces, next year. The scenario was earnestly rehearsed by an array of allied forces whose common language was English. A commander’s voice crackled over the radio, ordering troops to retake the town of Schnöggersburg and its airport. The air grew thick with dust and cordite as Leopard 2 tanks raced across the scrubby landscape, with howitzer fire providing cover and helicopters circling overhead. Fire-fights broke out across the rooftops, then Norwegian tanks rolled through the cleared streets and on to the airport. “I have spent 30 weeks in training with my troops and I can tell you: we will fulfil our mission,” affirmed Brigadier-General Ullrich Spannuth with evident pride.

In a narrow sense, he may be right. Whether supporting French troops in the Sahel, or training Kurdish fighters in Iraq, Germany’s soldiers usually rise to the challenge when a few of them are under an international spotlight. But the overall state of the Bundeswehr is dismal. At a time when many other states in the region are girding themselves against possible Russian adventurism, the German armed forces are desperately short of equipment, money and, above all, public support.

Lieutenant-General Jörg Vollmer, the Bundeswehr chief of staff, who reviewed the exercise from a rooftop, admits that fitting out the VJTF will come at a price. As he insisted, the force will now be supplied with the tents and thermal clothing which it was reported, earlier this year, to be missing. But if that goal is achieved, “equipment will be lacking elsewhere,” he says.

The contrast with nearby countries is stark. Sweden and Finland, although not even members of NATO, are working hard to boost their defences and galvanise their people as they observe increased Russian activity, above all by submarines, in the Baltic Sea. In May the Swedish government issued leaflets advising citizens what to do in the event of war, a step it has not taken since the 1960s.

The contrast with nearby countries is stark. Sweden and Finland, although not even members of NATO, are working hard to boost their defences and galvanise their people as they observe increased Russian activity, above all by submarines, in the Baltic Sea. In May the Swedish government issued leaflets advising citizens what to do in the event of war, a step it has not taken since the 1960s.

As for Germany’s NATO partners, Poland and the Baltic states, they need no persuading of the dangers of Russian adventurism, which has been concentrating minds in the alliance since 2014 when President Vladimir Putin annexed Crimea and fomented war in eastern Ukraine.

At least on paper, Germany’s armed forces are deeply involved in a reordering of NATO’s military structures which are designed, in a measured way, to respond to Russian assertiveness. Some 650 German soldiers are stationed in Lithuania, leading a multinational “tripwire” force which would be in the front line of any Russian incursion. The Bundeswehr and its two armoured divisions are taking shape as the linchpin of a new European defence order, with Dutch, Czech and Romanian units under German command. That, at least, is the theory. But as memories of the cold war fade, the willingness of German citizens to pay for their own defence, let alone anybody else’s, seems ever diminishing.

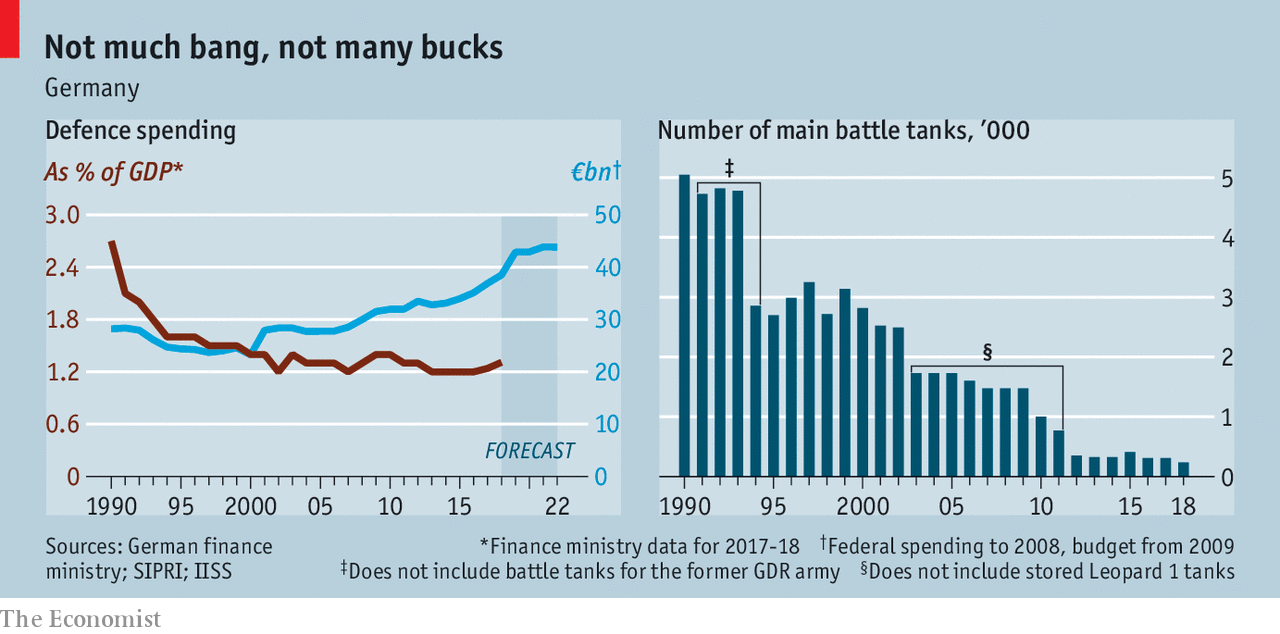

With his erratic outbursts at this month’s NATO summit, Donald Trump brought things to a head. He accused the Germans of being cynical spongers because their defence spending amounts only to 1.2% of GDP, compared with a NATO target of 2%—which in his view ought to be doubled.

As the president made thunderously clear, he was unimpressed by pledges from Chancellor Angela Merkel to raise the proportion to 1.5% by 2024. German citizens seem equally cool towards the idea, but for the opposite reason. An opinion poll at the time of the summit found that 36% of Germans thought defence expenditure was already too high, and only 15% approved of Mrs Merkel’s promise to raise it.

Defence-watchers in many countries were shocked by a report in February on the state of the Bundeswehr’s equipment. Less than half the country’s Leopard tanks, 12 out of 50 Tiger helicopters and only 39 out of 128 Typhoon fighter aircraft were fit for action. At the end of last year, none of the country’s six submarines was at sea. But German voters seem to shrug; when asked what sort of expenditure should be a priority, defence comes last. It barely featured in last year’s election.

The malaise afflicting the German armed forces has deep roots. For most of the time since reunification, the country has been slashing the numbers in uniform, from over 500,000 to 180,000. Current plans for a modest increase in numbers, to a total of about 200,000, will be hard to implement because military careers are so unpopular. Conscription ended in 2011.

In a country which has reason to be wary of militarism, any change of thinking about the country’s strategic role takes time to absorb. Only in the mid-1990s did the public leerily accept the idea of German troops being sent on far-flung missions, and even then only so long as just volunteers were dispatched and each operation had parliamentary approval. The country currently has 1,000-strong missions in Mali and Afghanistan, and not much more.

Before 2014, it was assumed that German troops were unlikely to hear shots in anger except on some cautiously chosen expeditions. As the Russian bear growled that year, military staff began planning for old-fashioned territorial defence, which is virtually inseparable from the defence of NATO neighbours. The public did not hear the growl, or chose not to hear it.

This article appeared in the Europe section of the print edition under the headline "Outgunned"

No comments:

Post a Comment