Introduction

The security of the European Union is being challenged like never before. Central tenets of the international system that Europeans helped build are eroding or even disintegrating one by one. Great power competition is increasingly shaping Europeans’ security environment, while other security threats are also on the rise, from terrorism and cyber attacks to climate change. The EU now faces security threats from its east and south – and an uncertain ally in the West. To the east, a new kind of uneasy neighbourly relationship with Russia is developing – one that appears to involve Europeans accepting Russian meddling in their political affairs, from deliberate interference in elections to cyber attacks on European companies, systems, and political machinery. Further east, China continues to deepen its influence on EU states through trade and investment in the Union and its neighbourhood.

To the south, European countries now rely on cooperation with an increasingly autocratic regime in Ankara on some of the issues that their citizens are most concerned about, particularly migration and counter-terrorism. Meanwhile, conflicts and poverty on the other side of the Mediterranean, and the migration that stems from them, are increasingly challenging Europe’s security and even its solidarity.

Most importantly, to the west, US President Donald Trump is demonstrating a total disregard for the international agreements and norms that Europeans hold dear. By withdrawing from the Paris climate change deal, by pulling out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on Iran’s nuclear programme, and by attacking the integrity of the international trading system through the unilateral imposition of tariffs, Trump has called into question Europeans’ formerly unshakeable faith in diplomacy as a way to resolve disagreements and to protect Europe. European leaders now fear that the transatlantic security guarantee will centre not on alliances and common interests but purchases of American technology and materiel – and on obeisance to an unpredictable president.

Europeans are – understandably – worried about this picture. But they are divided on how to handle it. The political crisis around immigration into the EU from 2015 onwards has revealed fundamental divisions in the way member states view their security. As Ivan Krastev has argued, “the refugee crisis exposed the futility of the post-Cold War paradigm, and especially the incapacity of Cold War institutions and rules to deal with the problems of the contemporary world.” For many Europeans, the migration crisis has called into question the ability of the EU and the global multilateral system to protect them.

There are divisions not only between but also within member states. In recent years, national elections across the EU have resulted in intense battles between political movements that favour an open, progressive agenda and global engagement, and those that prefer a nationalist, inward-looking approach that is, ultimately, anti-EU. In this unstable political environment, the need to keep citizens safe – a basic responsibility of any government – has taken on even greater importance. Safety is central to the nationalists’ increasingly popular arguments. They argue that mainstream EU governments have failed to protect citizens. In power, however, they face the inescapable dilemma that small European nations (and they are all small) cannot effectively respond to today’s threats through national policies alone.

Against this backdrop of worry and division, this report aims to understand security perceptions across the EU more fully and to search for common responses to protect the EU’s citizens. In April and May 2018, ECFR’s network of 28 associate researchers completed a survey covering all member states, having conducted interviews with policymakers and members of the analytical community, along with extensive research into policy documents, academic discourse, and media analysis. Based on this pan-European survey data, ECFR’s new report maps the security profile of all member states, identifying areas of agreement, points of contention, and issues on which they should cooperate to keep Europe safe.

The results reveal an EU that is fairly united in its understanding of the threats it faces, but that diverges significantly in the vulnerability it feels to those threats. This is not just a question of geography or size, since France and Germany, neighbours at the heart of Europe, fall nearly on opposite ends of the spectrum. France feels relatively resilient across the range of threats, while Germany thinks of itself as relatively vulnerable.

There are also important variations among the member states on what role the EU should play as a security actor. There is a near unanimous consensus that NATO must remain the backbone of European security, but EU member states differ significantly on the extent to which, within the NATO framework, Europe can or should begin to develop autonomy from the United States.

Finally, and somewhat sadly, given that there is no shortage of real threats for Europeans to be concerned about, our research paints a picture of an EU that is in some ways its own worst enemy. The responses on the preoccupation with immigration highlight the extent to which it is the political fallout of the migration crisis – its potential to increase support for populist parties and its use as a weapon in European domestic politics – and not migration itself that currently threatens the EU.

Rising fears

Europeans are united in their fear about the future. There is widespread agreement throughout Europe that security threats are on the rise: respondents to ECFR’s survey judged that the threats their countries faced intensified between 2008 and 2018, and will intensify further in the next decade. Today, the top five perceived threats are, in descending order: cyber attacks; state collapse or civil war in the EU’s neighbourhood; external meddling in domestic politics; uncontrolled migration into the country; and the deterioration of the international institutional order. Respondents expected the order of these threats to remain largely the same in the next decade (with terrorist attacks joining the deterioration of the international order in fifth place), and each threat to grow more intense in the period. Our researchers assess that, with the benefit of hindsight, the situation appeared to be slightly different in 2008, when the top perceived threats were, in descending order: economic instability and terrorist attacks; instability in the neighbourhood and disruption in the energy supply; and cyber attacks – of the kind Estonia experienced in April 2007.

The only threats that seem to have diminished in the past decade are those from financial instability and disruption in the energy supply. Respondents perceived all other threats to have intensified. They believed that the only threats that would diminish by 2028 were those from: an inter-state war involving their country or allies; the disintegration of the EU; disruption in the energy supply; and financial instability. They anticipated that all other threats would become more severe in the next ten years.

There has been little change in the international actors they perceive to be most threatening: jihadists continue to top the list, with Russia and international criminal groups sharing second place, and North Korea in third. Europeans expect these threats to persist until at least 2028. The most significant threat pertains to Russia. With Russia’s annexation of Crimea, perceptions of the country have shifted: in 2008, Europeans viewed Russia as the fourth largest threat they faced.

Given the frequency of terrorist attacks on European soil in 2008-2018, one might have expected a greater increase in Europeans’ fear of terrorism in the period, and in their projections on the threat’s severity in 2028. The reason why this is not the case might relate to a realisation that, rather than posing an existential threat, terrorism can be addressed through societal resilience. Member states are expecting the world to become more geopolitical: they expect the threats from jihadists, international criminal organisations, Russia, and North Korea to stay roughly the same in the next decade, and the threats from Turkey and China to grow in the period.

A divided union

The differences between EU countries’ threat perceptions form part of an oft-repeated narrative on European disharmony. For member states to create a coherent common defence and security policy, they need to define their fears and goals in a coherent way – perhaps borrowing (in style, if not in content) from the first NATO secretary-general’s famous claim that the alliance was founded “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”.

The conventional wisdom is that the EU’s internal divisions are particularly sharp on security and defence issues, with the east mainly concerned about Russia and the south predominantly worried about terrorism. But the results of ECFR’s survey suggest that the picture is more complex than this. Divergences in European threat perceptions are less apparent than the prevailing narrative would suggest, with terrorism and migration having to some extent made the southern neighbourhood a pan-EU preoccupation, and with cyber attacks and information warfare having increased concern about Russia in member states outside central and eastern Europe. Nonetheless, disagreements over how to address threats could become the most significant obstacle to the creation of independent European defence capabilities.

It is striking that, if we look at the EU average, most threats are seen as moderate or significant. The only outlier is the use of nuclear weapons against a European country, considered to be only a minor threat. Hence (on an aggregate EU level), no one threat eclipses the others. However, these aggregated numbers hide divisions.

Unsurprisingly, eastern and southern Europeans were particularly concerned about uncontrolled migration into their countries. Indeed, Slovenia, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, Malta, and Italy saw this as the most significant threat they face. Concern about international crime is a southern story, with Greece, Malta, Spain, and Portugal (but also Slovakia and Austria) considering it a high-priority threat. Fear of terrorism is particularly evident in larger countries and those that have recently experienced terrorist attacks (the UK, France, Spain, Germany, Denmark, and Belgium). Concern about Russia is strongest in the east (Estonia, Romania, Lithuania, Poland, and Finland), although Germany and the UK also perceive it as a major threat. Estonia and Lithuania are especially worried about Russian meddling in domestic politics.

These divisions initially appear to confirm the narrative on a divided EU. But there are few actual contradictions among Europeans even when their top priorities diverge: threats that are a top priority for some EU countries are generally a significant threat for the rest, while issues that many view as benign are at most “somehow a threat” for others. Such broad alignments will ease the search for common responses. There are only two exceptions to this rule. The first is Turkey, which ten countries consider to be no threat but two others (Greece and Cyprus) see as their top threat. The most problematic division is in European states’ perceptions of Russia, which seven countries regard as the most important to their security and six others as a significant threat, but which five, predominantly southern, countries (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Hungary, and Cyprus) view as no threat at all.

The differences in perceived vulnerability may be even more problematic. For instance, 15 countries feel “very resilient” or “rather resilient” to threats against their territory, while 11 others feel “rather vulnerable” or “very vulnerable” to such threats. These 11 countries might be more supportive of a Europe-wide military build-up while the others might judge it unnecessary. Equally, 16 countries feel vulnerable, while ten others feel resilient, to cyber attacks. There are also fundamental differences between countries: Finland, for instance, claims to be highly resilient against all threats, whereas Estonia, Belgium, or Portugal generally feel vulnerable. In this context, there is an interesting juxtaposition between France and Germany: the former’s perceived resilience to all threats contrasts with the latter’s overall sense of vulnerability.

ECFR’s survey thus shows that, over time, EU member states have not grown closer together on security and defence issues. While the disharmony narrative appears to exaggerate divisions between Europeans’ perceptions of threat (with the notable exception of the Russian threat), there are significant divergences between their perceived vulnerabilities. This, in turn, determines the urgency with which EU countries wish to counter threats, as well as their views on who should counter them and how they should do so.

Threatened by the new?

New threats have become a major concern. Three of the top perceived threats emerged relatively recently: cyber attacks, external meddling in domestic politics, and the collapse of the international institutional order.[1] Europeans perceive these threats as having grown much more severe in the last ten years.

Cyber is the area in which, according to ECFR research, EU countries feel most vulnerable. This is followed by external meddling in their domestic politics and then the more traditional threat of attacks on their territory. Interestingly, across the EU as a whole, these are also among the threats against which member states feel most resilient (a further indication of the extent to which it is difficult to talk about security perceptions shared across the EU).

Large and/or wealthy member states (such as Denmark, Belgium, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, and the UK) appear to be most concerned about cyber attacks – either in terms of their likelihood, impact, or manageability. This preoccupation must stem from an awareness of their societies’ reliance on digitised systems, since these countries are widely seen as “leaders” on cyber issues within the EU: France and Sweden have made significant progress in developing cyber strategies (and, indeed, France believes itself relatively resilient in this area); Denmark was the first member state to appoint a technology ambassador; the potential loss of UK cyber cooperation after Brexit is, according to ECFR research, a cause for worry among member states.

Who should protect Europeans?

EU member states broadly agree that NATO should remain the backbone of European security, and that the US should remain actively involved in Europe. But they differ on the role the EU should play in European defence.

The US remains a crucial contributor to Europe’s security, both through NATO and as an independent actor. Interestingly, however, Europeans valued technical military and intelligence cooperation with the US above any other American contribution, including troop deployments on European soil. They also placed a premium on high-level political, technological, and practical cooperation with the US. This is exactly the type of cooperation that has suffered most with America’s new approach to European security under the Trump administration. European states are scrambling to address America’s gradual withdrawal from the rules-based international order, and the administration’s decision to cast doubt on the US security guarantee for NATO allies. One answer could be to cater to US demands: 13 EU member states would be willing to make unspecified concessions to ensure that the US remained “in” Europe. But many of them would also opt to strengthen Europe’s capabilities: 14 member states advocate “pushing firmly for defence and security integration in the EU”, and 16 member states favour “upgrading and updating national defence capabilities by increasing spending”. Nonetheless, despite their greater willingness to do more for Europe’s security, Europeans are not quite willing to let go of the US. To many, the EU is still a transatlantic geopolitical project.

EU member states differ most on the desirable level of European autonomy from the US. Some believe that an increased EU role in European security and defence will make them safer and allow them to survive without the US, if needed; others want to use enhanced European capabilities in these areas to convince the US to stay engaged with Europe; others still worry that, by improving its capabilities, the EU will compete with NATO and thereby weaken the transatlantic bond. It is here that the EU faces its most significant problem, as these gaps appear to be unbridgeable – even through flexible solutions do not need to include all member states. If some states believe that increasing European defence cooperation will ultimately threaten Europe’s security by weakening the transatlantic bond, they will likely be unwilling to allow others to build an integrated European defence order. Proceeding with flexible integration might, once progress is made and credibility regained, alleviate many of their current fears. But there is a real danger that some member states will become spoilers in others’ security projects.

In this context, Europeans’ views on whether the US is a threat could be decisive, because a shift in these views could help clear the way for such projects. No EU member state views a threat from the US as a priority issue. However, a minority of member states believe that the US is either “somehow a threat” or a “moderate threat”. According to ECFR’s survey, the number of EU states that view the US in this way will rise from 5 to 8 between 2018 and 2028.

The rules of geopolitics are shifting, as European leaders have acknowledged ever more explicitly during Trump’s time in the White House. After attending the 2017 NATO summit and G7 meeting in Italy, German Chancellor Angela Merkel commented in May 2017 that “the times in which we could rely fully on others – they are somewhat over”.[2] By June 2018, following Trump’s 11th-hour withdrawal from the G7 communiqué, she had hardened her position to “we, as Europeans, have to take our fate more into our own hands” and raised the issue of “where must we be able to intervene alone”.[3]

Germany: centrist or outlier?

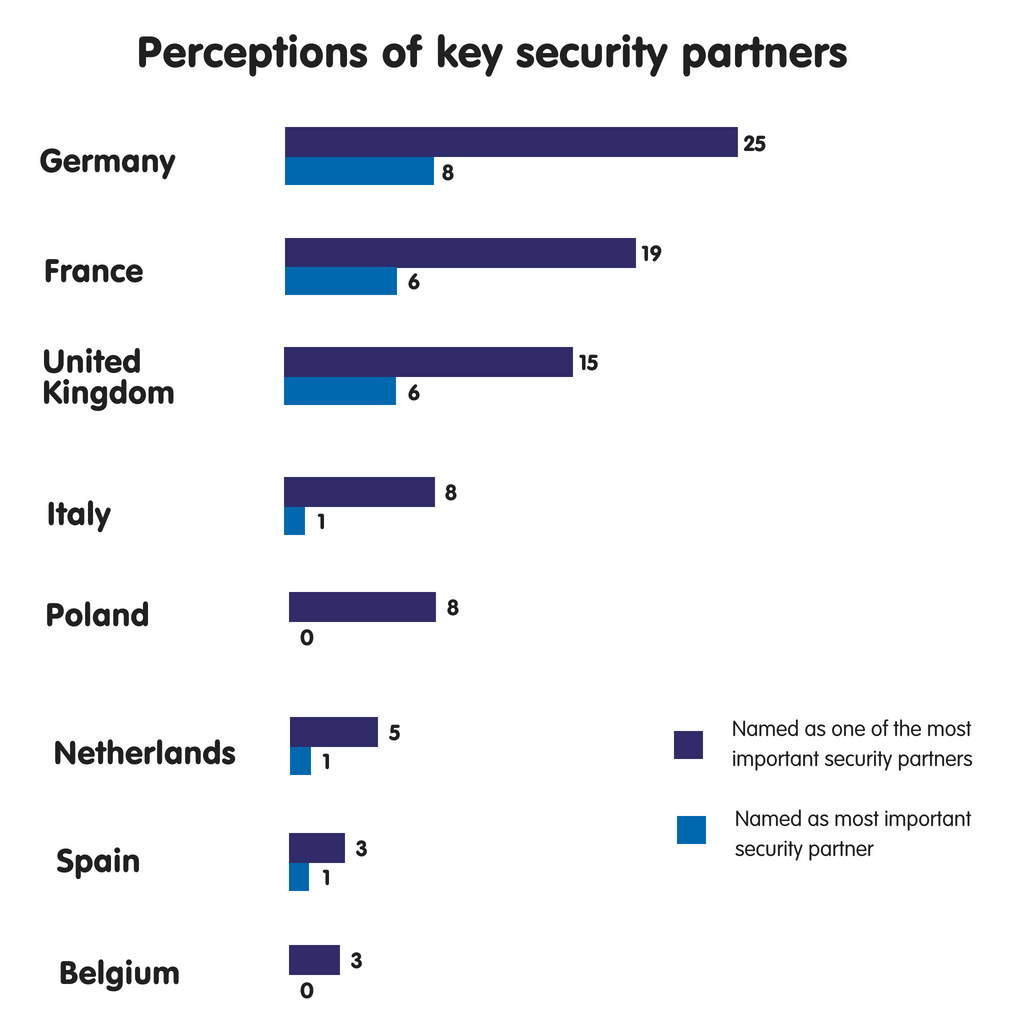

Because of its size, location, and economic power, Germany has always been a central player in the EU. ECFR’s survey shows the extent to which this is true even in security and defence – areas in which, for historical reasons, the country has shown marked reticence. A striking 25 EU countries (all but Portugal and Cyprus) name Germany as one of their “most important partners in security”. Although this seems to support the narrative on a Germany-centric, hub-and-spokes Europe that has gained acceptance in recent years, the reality is more complex. Germany may top the list, but the much lower number of eight countries see it as their most important partner, while survey respondents named 22 other countries as an important security partner. The multilateral EU, it seems, is alive and well.

Despite some recent movement towards increasing its defence spending, Germany continues to see itself as a “civilian power”. Sometimes, the justification for this stance centres on the argument that other European powers, particularly those that suffered under Nazi occupation during the second world war, would not accept a more militarily capable Germany. However, ECFR’s survey shows that there is little basis for this argument. None of the 28 EU member states expressed concern about Germany upgrading its armed forces, increasing its defence spending, or participating more in military missions. Rather, 15 countries would “highly welcome” these changes. Among ruling European parties, only Poland’s Law and Justice cultivates fear of Germany rooted in the second world war – and even it would still like to see Germany increase its military spending as a contributor to NATO. Moreover, the stark contrast in our research findings between a confident France, which regards itself as resilient across the board, and Germany, which feels vulnerable in most areas, underlines the importance of perceptions in threat assessments. Perhaps the extent of the debate in Germany about the kind of security actor it should be plays a role in perpetuating this sense of vulnerability, whereas France’s strategic posture, which has been relatively constant between recent administrations, is subject to review but not to the same level of debate.

With the advent of the Trump administration, the transatlantic relationship has taken a major hit. Nowhere is this more visible than in US-German relations. As noted above, several countries have expressed concern about the United States’ trajectory, noting that the US may have become “somehow a threat”. Only Germany regarded the US as “a moderate threat” in 2018. Trump’s anti-German rhetoric and protectionist trade policies have damaged “export world champion” Germany more than any other EU country. This is likely to put the country and its leader in a particularly awkward position. Merkel has always rejected the notion that the German chancellor could become the leader of the free world in the US president’s stead. But Germany’s special position in Europe means that it is especially problematic for it to have such a poor relationship with the US.

What is to be done?

How can Europeans allay their fears about the future? How should they equip themselves to cope with an increasingly threatening environment?

Security begins at home, or so the dictum goes. It is hard not to be reminded of this when considering the security issues that preoccupy EU member states. In the responses to ECFR’s survey, there is an undercurrent of concern that the EU is doing too little to address its perceived vulnerabilities. This concern seems particularly acute in relation to possible attacks from Russia. The Russia-related issues that concern Europeans most are: the likelihood of cyber attacks; an inability to effectively respond to interference in domestic politics; a lack of adequate defences against information warfare; and the pliancy of European public opinion. (Hungary was the only member state that equated such interference with Brussels; all others identified Russia as the main threat in this area.)

Europeans believe that they are especially vulnerable to cyber attacks and interference in domestic politics. This suggests that the EU and its member states should prioritise efforts to build resilience in the face of these threats. By focusing primarily on the threat rather than the actor that many – but not all – see as responsible, Europeans may find new ways to bridge their differing perceptions of Russia. They have already done so in some areas, as seen in the Greek-led Cyber Threats and Incident Response Information Sharing Platform and the Lithuanian-led Cyber Rapid Response Teams and Cyber Mutual Assistance Programme under PESCO, as well as the European External Action Service’s Strategic Communications Division. But dealing with cyber attacks when they come, or information warfare in the heat of the battle, will only ever be part of the answer. To address the areas in which Europeans feel most vulnerable, the EU will also need to build resilience closer to home. The weakest links in any computer system – those that hackers are most likely to target – are usually accounts or data held by private citizens. Improving their understanding that they are actors in cyber security (and not only victims of inadequate protection) will be crucial. Similarly, Europeans should not only be concerned that external actors are able to manipulate information, but also that many of their fellow citizens – as consumers of information and as voters – find these arguments persuasive, or are unable to identify fake news. European leaders need to improve public understanding of these issues, and to display courageous and creative political leadership in developing convincing alternative narratives to that of inward-looking nationalism on issues voters care about.

ECFR’s survey suggests that Europeans’ intense concern about migration – which the spring 2018 Eurobarometer identifies as the most significant issue the EU faces – is in no small part of their own making. Their primary fear is not that terrorists will enter Europe via migration routes (although some expressed concern about this) but rather that migration will create damaging political fallout within the EU. The issue that most concerned respondents (representing 17 member states) was an inability to control the number of refugees arriving in Europe. But this is not in itself a security threat: even at peak levels of the migration crisis in 2015 and 2016, the EU was able to absorb the number of arrivals collectively – although the per capita levels of arrivals posed challenges for member states such as Austria, Germany, Malta, and Sweden.[4] But an inability to control the number of arrivals potentially poses a political threat to the government in any EU member state, given that the debate around the issue has become so toxic.

The second most common reasons for concern about migration were an inability to control the type of migrants that arrive in Europe, and the impact of this on member states’ capacity to work together (11 member states). They have reached an impasse on migration due to battles between member states with shared borders; between supporters and opponents of the controversial relocation scheme introduced in 2016 as a way to share the burden of arrivals internally; and between those who want to change the Dublin system – principally, states on the EU’s southern border – and those that want to preserve it – largely, those that only border other EU countries. (The UK is absent from this discussion because it is preoccupied with negotiations on its departure from the EU.) The hardened positions emerging from the new Five Star/Lega government in Italy and the Christian Social Union in Germany in recent weeks have only intensified these battles.

European policymakers must work with citizens and the political environment in their countries if they are to address security challenges. There is a need to reassess the EU’s ability to implement migration deals that promise “mobility partnerships” (increased numbers of visas to work in the EU for third countries, in return for them hosting migrants who failed to meet EU entry criteria). Deals that fail to deliver the promised control over migration into Europe only add to European citizens’ sense of vulnerability, and third countries’ doubts about the EU’s credibility. Resolving the political crisis around migration will require stronger political leadership within the EU – to rebuild a consensus on a collective European answer to increased migration levels that aligns with the EU’s founding principles of openness, tolerance, and fairness – as much as border management or foreign and security policy.

Furthermore, Europe needs to build up its defence capabilities – and not because Trump is telling it to. Few of the greatest perceived threats to the EU are directly linked to these capabilities. But the more secure Europe is in a conventional sense, the more robust it can be in its response to actors posing new threats. And responses to many of the threats that most concern member states – including terrorism, and the risk of state collapse in Europe’s neighbourhood – will have a defence component, either through military deployments or, indirectly, efforts to improve geopolitical standing.

The two arms of foreign and security policy are mutually reinforcing: although threats may be evolving, an adversary’s awareness that it is at a military disadvantage will always strengthen the hand of European diplomats. In a world of hybrid threats and geopolitical competition among actors who trade in all types of power, EU states cannot afford to ignore the utility of force.

They are gradually realising this. Merkel has recognised that Europe’s security order cannot be principally based on the transatlantic partnership when the gap in world views between leaders on either side of the Atlantic is too wide. She has also acknowledged that, to become a security power commensurate with its economic importance, the EU needs to rethink its calculations on military capability. French President Emmanuel Macron wants to strengthen Europe’s intervention capabilities, and he aims to harmonise European strategic culture through increased military exchanges. To prepare for the turbulence Europeans expect from the future international environment, the EU will need to invest more in everything from intelligence and cyber capabilities to development aid. The focus of this effort should be not only increasing overall levels of investment, but also increasing its effectiveness through improved targeting. As our colleague Nick Witney has argued, “European dependence on American protection is absurd, given that the 28 EU member states between them are second only to the US in their defence spending, and in 2017 outspent Russia by a factor of [3.5].”

The launch of PESCO is a good thing – as is growing political coordination between EU states on security and defence. Three-quarters of respondents to ECFR’s survey believed that PESCO contributed to their country’s security. But, at its most basic level, the process of working together, thereby strengthening collective responsibility for European security and defence, is important in itself as the groundwork for developing a more robust security posture.

In this context, member states should keep in mind that their overriding goal should be European rather than EU security and unity. European citizens’ growing security fears should be seen not as a catalyst for unifying the EU but the impetus for improving Europe’s defences inside or outside the Union. “Mini-lateral” initiatives – such as the French-led European Intervention Initiative (which as of its June 2018 launch included the UK and was open to third countries) and the British-led Joint Expeditionary Force – create opportunities for cooperation between countries with similar strategic cultures and threat perceptions.

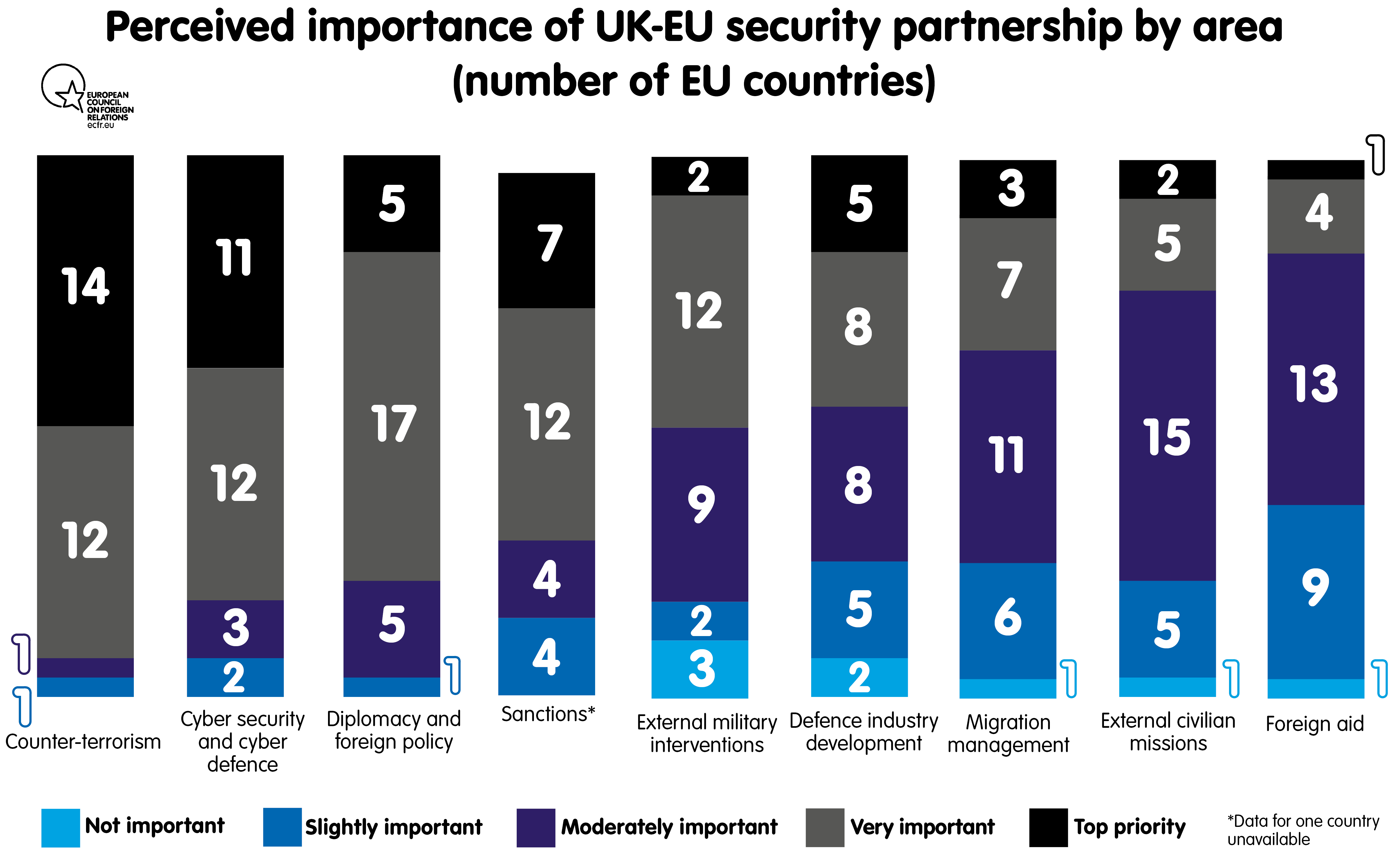

Brexit may hamper such efforts. Nearly two-thirds of respondents to the survey suggested that the UK’s departure from the EU would have a negative or very negative impact on their security. Just as the EU27 felt most vulnerable in many of the same areas, they broadly agreed on the security issues they expected to address in cooperation with the UK after Brexit. Respondents most often described counter-terrorism, cyber security and cyber defence, and sanctions as the most important elements of cooperation. Yet both the UK and the EU27 are allowing a row over the Galileo satellite project and the wider Brexit negotiations to sour talks on their future security partnership. It is possible that the sides need a cooling-off period to prevent them from accidentally sabotaging arrangements crucial to European security.

Recognising that geopolitical competition is likely to intensify during the next decade, EU states need to continue to invest in the diplomatic capacity necessary to pursue an assertive foreign policy as a crucial element of European power. There is a broad range of urgent foreign policy challenges that has a major bearing on European security – from salvaging the JCPOA and defining the EU’s relationship with the western Balkans to determining Europe’s relationship with African countries in an era of large-scale migration. Only Europe’s best diplomatic minds can meet these challenges.

More immediately, the EU needs to remain united through the upcoming NATO summit. As discussed above, EU countries are divided between those that believe increased European defence cooperation will ultimately hurt Europe’s security by weakening the transatlantic bond and those that wish to respond to an unreliable US by further integrating Europe. These differences in world view will not disappear in time to confront Trump’s call for Europeans to spend more on defence (particularly American technology and materiel) or to significantly reduce European dependence on the US. But by adopting a more flexible, multispeed approach to its security, Europeans may begin to carve out autonomous strategic capabilities.

The authors would like to thank Compagnia di San Paolo, without whose financial support this research would not have been possible. They would also like to express their gratitude to ECFR’s European Power team, especially Josef Janning, Almut Möller, Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, and Nick Witney for their helpful comments. Special thanks goes to Jeremy Shapiro, Katharina Botel-Azzinnaro, and Chris Raggett for editing. This report relies more than anything on the tireless work of our 28 researchers across Europe, to whom the authors are deeply indebted.

About the authors

Susi Dennison is a senior policy fellow at ECFR and director of the European Power programme, which focuses on the strategy, politics, and governance of European foreign policy at this challenging moment for the international liberal order. She previously led ECFR’s European Foreign Policy Scorecard project for five years, and worked with ECFR’s MENA programme on north Africa. Before joining ECFR in 2010, Susi worked for Amnesty International in its European Union office. Susi began her career in HM Treasury in the United Kingdom.

Ulrike Esther Franke is a policy fellow at ECFR, and part of ECFR’s New European Security Initiative. She works on German and European security and defence, the future of warfare, and new technologies such as drones and artificial intelligence. She has published widely on these and other topics – in, among others, Die ZEIT, FAZ, RUSI Whitehall Papers, Comparative Strategy, War on the Rocks, Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik – and regularly appears as a commentator in the media.

Pawel Zerka is a programme coordinator at ECFR based in the Paris office. He coordinates the European Power programme and ECFR’s New European Security Initiative. Pawel holds a PhD in economics and an MA in international relations. His main areas of expertise include EU affairs, Latin American politics, international trade, and Poland’s European and foreign policy.

[1] When rankings as either a “top priority” or “significant” threat are added together, the second most common answer was state collapse in the neighbourhood, which is not a particularly new threat.

[2] Merkel’s comments at a Munich election rally, 28 May 2017.

[3] Merkel’s comments on Anne Will talk show, 10 June 2018.

[4] Sweden 20.3; Malta 18.2; Austria 10.7; Germany 8.1 per 1,000 inhabitants in 2016, according to Eurostat data used in Stefano Torelli, “Migration through the Mediterranean: Mapping the Eu Response”, ECFR, May 2018, available at www.ecfr.eu/specials/mapping_migration.

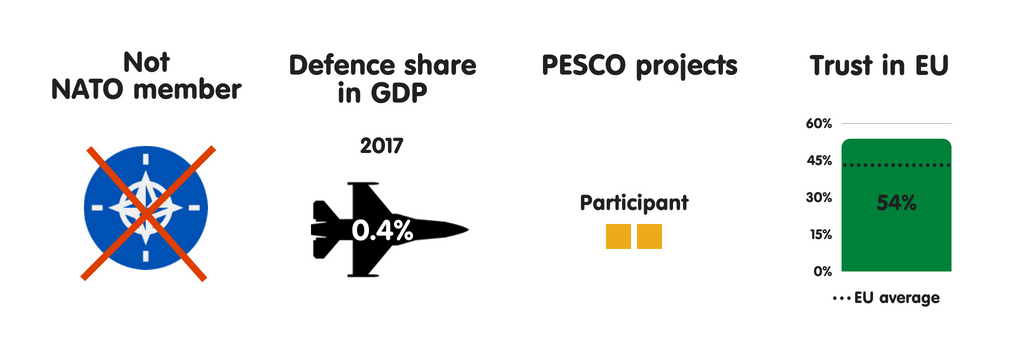

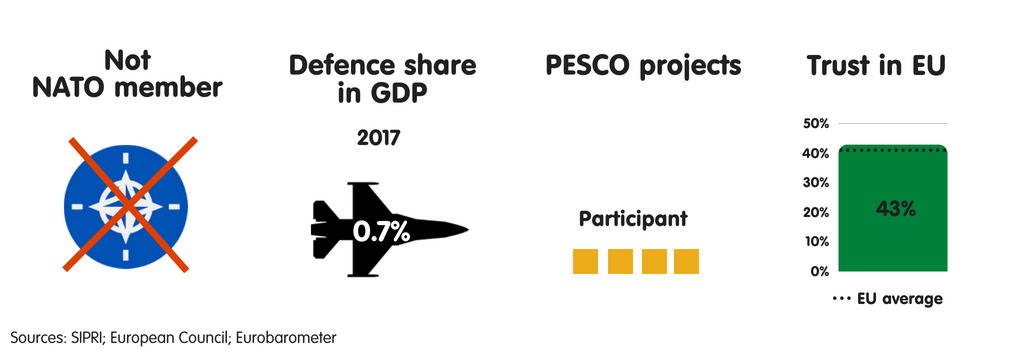

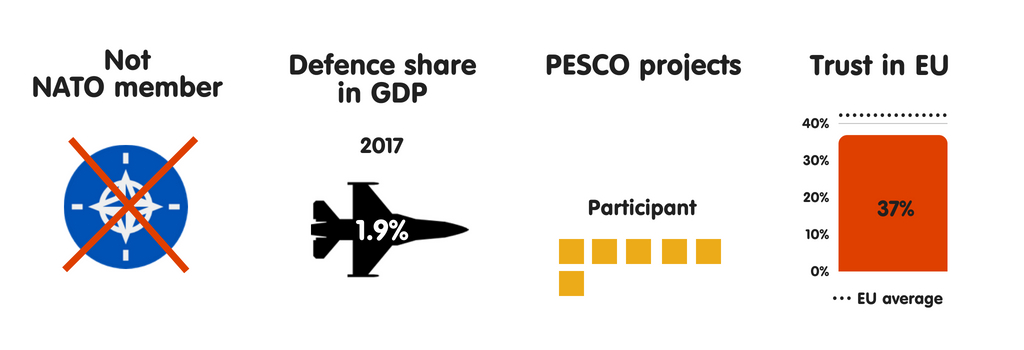

AUSTRIA

What does the country fear?

Due to its position on the Western Balkans migration route to Germany, Austria has experienced some of the highest levels of migrant arrivals per capita in the European Union since 2015, when the refugee crisis began. As a result, Austria’s top perceived threats are uncontrolled migration, the risk of state collapse in the EU’s neighbourhood, and the disintegration of the EU. During its July-December 2018 EU presidency, the country will focus on migration above all else. Although Austria’s threat perceptions have changed significantly since 2008, there is a widespread expectation that they will change little in the next decade – albeit with cyber attacks and threats to the rules-based international order taking on a greater perceived importance.

Who does the country fear?

Austria sees international criminal organisations and jihadists as the most threatening actors it faces. The country perceives a moderate threat from Turkey and North Korea, and expects the threat from China, Iran, and Russia to grow over the next decade. Austria’s neutrality is an important part of its national identity, but it feels rather vulnerable to traditional threats – particularly military attacks on its territory. It believes that it is more resilient to threats such as cyber and financial destabilisation.

Essential security partners

Austria perceives Germany as its key security partner, partly due to the close coordination between the countries on cross-border crime and terrorism. Austria is a member of the Central European Defence Cooperation – which includes Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, and, as an observer, Poland – and works within this mini-lateral format on joint training exercises, pooling and sharing of military capabilities, and cooperation on handling migration. As a neutral, non-NATO country, Austria has a more distant relationship with the United States than most of its EU partners. However, in recent years, there has been a rise in intelligence exchanges between the countries due to their participation in the coalition fighting against the Islamic State group.

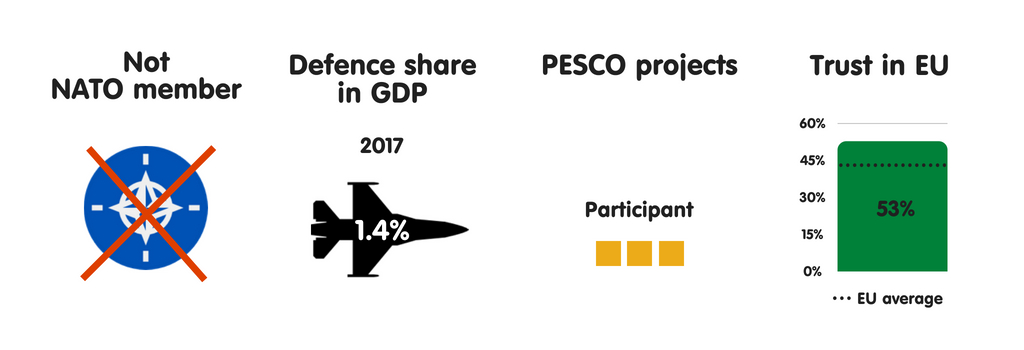

The EU as a security actor

Members of Austria’s political establishment largely agree that the EU should become a more credible actor in foreign, security, and defence policy, and that the country should actively shape debate on this issue. As a non-NATO country, Austria sees the EU as a vital forum for dealing with security and defence issues. Vienna is generally supportive of PESCO, seeing the project as a first step towards enhancing defence cooperation with its European partners.

BELGIUM

What does the country fear?

Belgium sees terrorist attacks as the most significant threat to its national security. This is the result of Islamic State group operations in Belgium and France in recent years, especially the suicide bombings at Brussels Airport and Maalbeek metro station in March 2016. Belgium has also been the base of operations for several terrorist attacks in France, including those in Paris in November 2015. These events have significantly changed the mindset of Belgian political leaders, raising their awareness of intelligence agencies’ important role in protecting society. Belgium also regards external meddling in domestic politics and cyber attacks as major threats, recognising the state’s lack of resilience in these areas.

Who does the country fear?

Belgium perceives jihadists as the most threatening actor it confronts. Other significant perceived threats include China, Russia, and international criminal organisations. Interestingly, Belgium has also begun to see the United States as a kind of threat. US President Donald Trump’s actions have widened a pre-existing Belgian political divide in which the right sees NATO as Belgium’s main security provider and the left views the alliance with greater scepticism. However, despite Trump’s efforts to undermine the international liberal order, Belgium still perceives the US as one of its closest allies.

Essential security partners

Belgium sees all four of its neighbours – the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and Germany – as its most essential security partners. This has much to do with not only historical cooperation patterns, but also the transnational character of terrorist groups. (France and Germany also perceive such groups as the greatest threat they face.) The US plays a major role in Belgium’s security, particularly through NATO and its nuclear guarantee. There is a US Air Force base in Chièvres and – despite the Belgian government’s statements to the contrary – the US has stationed B-61 nuclear bombs at Kleine Brogel Air Base. Although Belgium wishes to be seen as a reliable transatlantic ally, its low defence spending remains a problem in achieving this.

The EU as a security actor

In Belgium, as in most other EU countries, the establishment largely views the European Union as a transatlantic geopolitical project that has NATO as its backbone. The government plans to steadily increase its military budget during the next 20 years to keep the US in Europe. Yet, in keeping with its long-term policy, Belgium supports European defence cooperation, including that through PESCO. Nonetheless, it sees the initiative as a mechanism for improving transatlantic cooperation rather than for creating an independent European defence capability. Belgian leaders are also interested in strengthening European defence industrial cooperation to boost the small and medium-sized enterprises that dominate the country’s industrial sector.

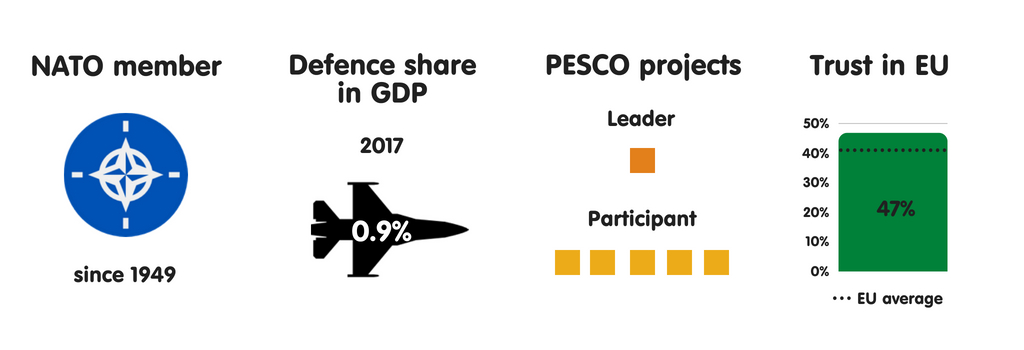

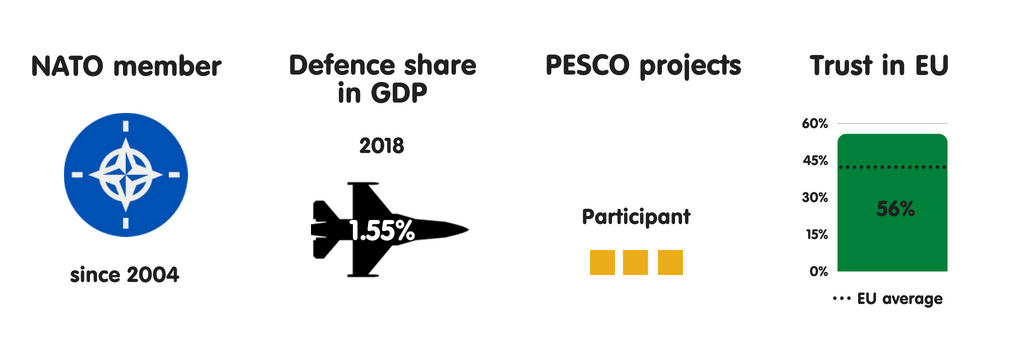

BULGARIA

What does the country fear?

Bulgaria is one of seven EU countries that perceive uncontrolled migration as the most significant threat to national security (the others are Italy, Greece, Malta, Slovenia, Hungary, and Austria). Bulgaria fears not just an inability to control the number or type of people who migrate to Europe but also, given the country’s declining population, the possible impact of migration on community cohesion. Other significant perceived national security threats include state collapse or civil war in Europe’s neighbourhood (a fear stemming from Bulgaria’s location on its southern border) as well as external meddling in domestic politics. Confident in its EU and NATO membership, Bulgaria sees little threat of military attacks on its territory. The country also perceives hybrid warfare and cyber attacks as rising threats.

Who does the country fear?

Bulgaria’s threat perceptions centre on no single country or actor. This is largely due to the fundamental divide in views on security in Bulgarian politics. Although Bulgarian parties have largely held to a consensus on the importance of EU and NATO membership since the late 1990s, only the larger party in the ruling coalition is pro-EU and pro-US; its smaller coalition partner is strongly pro-Russian and sceptical of both NATO and the European Union. All parliamentary opposition parties (as well as the president) are pro-Russian to varying degrees. Unsurprisingly, there is usually no direct reference to Russia in Bulgaria’s national security papers. Similarly, there are rarely any references to Turkey in these papers, as Bulgarians view the country as both a NATO partner and, increasingly, as a security threat. In this context, Bulgaria identifies jihadists as the most significant threatening actor it confronts.

Essential security partners

Bulgaria’s most important European security partners are other NATO members, particularly Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Bulgaria also engages in extensive cooperation with neighbouring Greece, especially on Balkans issues. Yet the United States remains Bulgaria’s most important security partner by far. Bulgarians view the US nuclear guarantee as essential to their security. There are four joint military facilities (US bases) in Bulgaria, with Sofia and Washington having agreed that the US can station up to 2,500 soldiers in the country. Bulgarians see technical military and intelligence cooperation with the US as very important. Based on an official defence ministry document, Bulgaria envisages a gradual increase in defence spending in the coming years – from 1.55% of GDP in 2018 to 2% of GDP in 2024.

The EU as a security actor

Regarding NATO as the cornerstone of its security, Bulgaria focuses on maintaining strong transatlantic ties. However, the country also participates in PESCO, while its main political parties – including those that are pro-Russian – largely support EU security and defence cooperation. In Bulgaria, the main driver of support for PESCO is a desire to avoid a multi-speed Europe and to move as close as possible to the EU core. Virtually no Bulgarians oppose PESCO. Still, some are concerned that European defence industry cooperation could harm Bulgaria’s small companies. It is one of four EU members to express such a concern (the others are the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Sweden).

CROATIA

What does the country fear?

Uncontrolled migration is among Croatia’s most significant national security concerns. Croatians are particularly worried that the Balkans migration route will reopen in summer 2018, and that a Croatia-to-Italy human trafficking route will open – challenges that Croatian police lack the resources to tackle effectively. Croatia’s other major national security concerns include state collapse or civil war in the EU’s neighbourhood (a fear stemming from Croatia’s proximity to the Mediterranean) and disruptions in the energy supply. Croatia is one of four EU members to see such disruptions as a threat (the others are Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland).

Who does the country fear?

Croatia considers international criminal organisations to be the most significant threat to its security. This has much to do with the country’s location in the Balkans, through which many smuggling routes run. For example, most heroin smuggled into Europe moves through the region. Croatia is exposed to the weakness of institutions in neighbouring non-EU countries, which are unable to counteract complex forms of organised crime. Despite Croatia’s NATO membership and a strong bipartisan consensus on most national security issues among the country’s leaders, a growing number of Croatians support the pro-Russian, anti-EU Human Wall, which has a fair chance of becoming Croatia’s third most influential political party.

Essential security partners

Croatia has few close security partners in Europe beyond its NATO allies. With several changes of government over the past few years, the country has primarily focused on internal affairs at the expense of foreign policy. Nonetheless, President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic and Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic – the two main architects of the country’s foreign and security policy in the period – have created substantively different visions of the country’s security priorities. Believing that his country should move as close as possible to the EU’s core, Plenkovic considers Germany to be Croatia’s main security partner. Meanwhile, Grabar-Kitarovic has cultivated strong relations with Poland and other Visegrád countries – as evidenced by a joint Adriatic-Baltic-Black Sea initiative that, beyond its infrastructural and economic elements, could be designed to weaken German influence in central and eastern Europe.

The EU as a security actor

Croatia usually adopts a pragmatic approach to security issues on the international stage, working to please both its EU and NATO partners. In this spirit, parliamentary speaker Gordan Jandrokovic issued in April 2018 a statement on PESCO in which he stressed that “cooperation must be conducted based on principles of inclusiveness, solidarity, and complementarity with NATO, without the duplication of activities and with respect to [member states’] decision-making autonomy”. From Croatia’s perspective, the EU and the United States have a particularly important role to play in the stability of the Western Balkans, given that Russia appears to be working to restore its sphere of influence there.

CYPRUS

What does the country fear?

Cyprus’s main security concern is the potential outbreak of an inter-state war involving it or its allies – a worry stemming from the fact that Turkey has occupied the northern part of the island since 1974. Lacking a political settlement or peace agreement on the occupation, many Cypriots fear that Ankara will engage in further direct military action against their country, perhaps employing hybrid warfare techniques.

Who does the country fear?

Cyprus is one of three EU countries that view Turkey as a significant or top-priority threat to national security (the others are Greece and Bulgaria). Yet Cypriots believe that they can agree on a comprehensive settlement with the Turks, which would enable the sides to build a constructive relationship and thereby change threat perceptions on the island. Cyprus also regards jihadists as a significant threat to their security, given their country’s proximity of the Middle East and north Africa. Like Rome, Lisbon, Athens, and Budapest, Cyprus does not see Moscow as a threat. Cyprus tries to maintain balanced relations with the United States, Russia, China, and Iran.

Essential security partners

Cyprus views Greece and France as being among its essential security partners in Europe. Cyprus and Greece have very similar security concerns, such as the perceived threat from Ankara, and stability in the Middle East and north Africa. The countries often coordinate their foreign policy initiatives. Cyprus maintains good relations with the United Kingdom, which pledged to secure the territorial integrity of the island under the treaties signed in 1959. Cyprus also considers the US to be a strategic ally, even if the American contribution to the island’s security is restricted to technical military and intelligence cooperation. Having implemented an arms embargo on Cyprus in 1992, the US remains unable to supply materiel to any military forces in Cyprus other than UN units.

The EU as a security actor

As a non-NATO member, Cyprus strongly favours the establishment of a Europe-wide security and defence policy. The country believes that greater integration of European armed forces would improve its security. As a consequence, Cyprus has a positive attitude towards PESCO, participating in a large number of projects for a country its size. Cypriot leaders believe that, in the long run, the EU will maintain a good level of security cooperation with the US only if it increasingly becomes a credible and autonomous foreign policy and security player, both in its neighbourhood and globally. Cyprus is especially supportive of greater EU involvement in the MENA region. In cooperation with Greece, it has set up two trilateral dialogues (with Israel and Egypt separately) to address crises in the region.

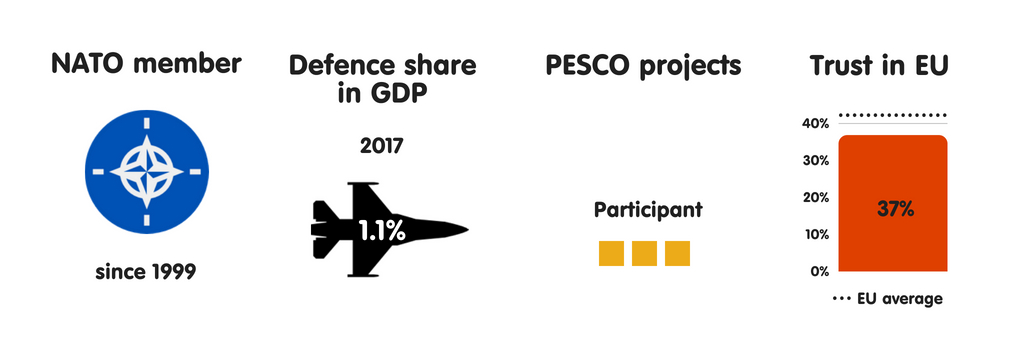

CZECH REPUBLIC

What does the country fear?

There is a gap between the Czech public and the Czech government in perceptions of security threats. The public are most concerned about migration and terrorist attacks, while the government is aware that the Czech Republic is neither a popular destination for migrants nor priority target for terrorists. Czech elites believe that the most important threats to their country are state collapse or civil war in the European Union’s neighbourhood (a concern stemming from its proximity to Ukraine), cyber attacks, and external meddling in domestic politics. Politicians on the Czech Republic’s extreme left and extreme right, as well as the openly pro-Russian president Milos Zeman, spread fear of uncontrolled migration and terrorist attacks to boost their political position.

Who does the country fear?

The Czech political establishment regards Russia and jihadists as the most threatening actors their country faces. Its view of Russia has rapidly dimmed in recent years, particularly since Moscow’s annexation of Crimea and instigation of a conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014. However, while seven of nine parties in parliament are wary of Russia and largely supportive of the EU and NATO, the extreme right and extreme left view Moscow as an ally and Washington as an enemy, demanding that the Czech Republic leave NATO. Zeman’s pro-Russian views have helped the extreme right’s and extreme left’s views enter mainstream public discourse (even though he declares himself to be pro-European and a staunch admirer of US President Donald Trump).

Essential security partners

The Czech Republic views Germany as its most important European security partner, due to the strategic dialogue between the countries and Berlin’s leadership in shaping EU security policy. Prague also engages in close security cooperation with Bratislava and Warsaw, with which it has many shared security interests and threat perceptions. Prague sees Paris as another important partner, mostly because of French security capabilities and leadership within the EU. However, the Czech Republic has perceived the US as its main security guarantor during the last three decades, despite the fact that their bilateral cooperation has declined in recent years. Partly to please the US administration, the Czech government has pledged to increase defence spending to 2% of GDP by 2024, almost double its current level.

The EU as a security actor

Prague sees NATO as vital to national security, and the EU as primarily an economic cooperation project. Nonetheless, there is a consensus among Czech civilian and military leaders that, in the long run, the EU should play an active role in developing European military and crisis management capabilities. Despite the Ministry of Defence’s initial scepticism about PESCO, the Czech government eventually joined the initiative (albeit minimally) as a way to improve national military preparedness. Prague remains wary of European defence industry cooperation, fearing that this could weaken the defence industrial base of the Czech Republic and other small EU countries.

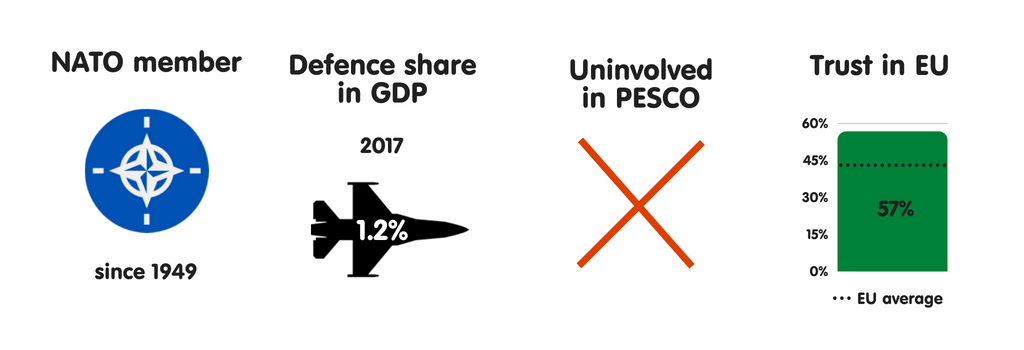

DENMARK

What does the country fear?

The Danish political establishment is most concerned about terrorist attacks and cyber attacks, followed by uncontrolled migration, the potential disintegration of the European Union, and the deterioration of the rules-based international order. These fears are partly linked to the EU refugee crisis, which led to several thousand refugees entering Denmark in late 2015.

Who does the country fear?

Unlike other EU countries, Denmark fears that Russia will increasingly militarise the Arctic, and that China’s assertiveness will become a threat to national security. According to its latest annual intelligence report, Denmark sees jihadists as the most threatening actors it faces. The country has become more alert to this threat since joining the coalition fighting against the Islamic State group, and since learning that more than 100 Danes have fought alongside extremist groups in Iraq and Syria (many of them have returned home). Denmark has experienced two jihadist operations in recent years: the 2015 Copenhagen shootings and the 2016 Kundby bomb plot. Denmark also views Russia as a major threat (although Danish parties on the extreme right and extreme left are less concerned about this than their mainstream counterparts). Danes expect that, during the next decade, Russia may become Denmark’s highest priority threat, partly because of its activities in the Arctic.

Essential security partners

With the United Kingdom having been Denmark’s most important European partner on security and defence, Brexit constitutes a major challenge for Copenhagen. There is a widespread concern among Danes that, as the only other country with an opt-out from the military aspects of the Common Security and Defence Policy, Denmark could lose influence within the EU after Brexit – and that strained EU-UK relations could have negative consequences for Danish security more broadly. Denmark’s other essential European security partners include France, Sweden, and Germany, as demonstrated by their involvement in joint training exercises and cooperation on international operations. Denmark and the United States have long maintained a close alliance. However, Copenhagen is concerned about Washington’s commitment to the rules-based international order under President Donald Trump – a worry that recently prompted it to increase military spending.

The EU as a security actor

The transatlantic relationship continues to provide Denmark’s most important security framework. However, Copenhagen has started to recognise the need for Europe to take more responsibility for its own security, particularly given the growing assertiveness of Russia, the terrorist threat, a rise in uncontrolled migration, and the unpredictability of the US administration. Nonetheless, Denmark is in the odd position of being unable to participate in PESCO due to its EU defence opt-out. The initiative’s recent launch has sparked a debate about the consequences of the Danish defence opt-out. The Danes are discussing the possibility of a referendum on repealing the measure, which could enable Denmark to participate in EU security and defence integration (there is only a slim prospect that such a referendum will take place and allow for the repeal of the opt-out).

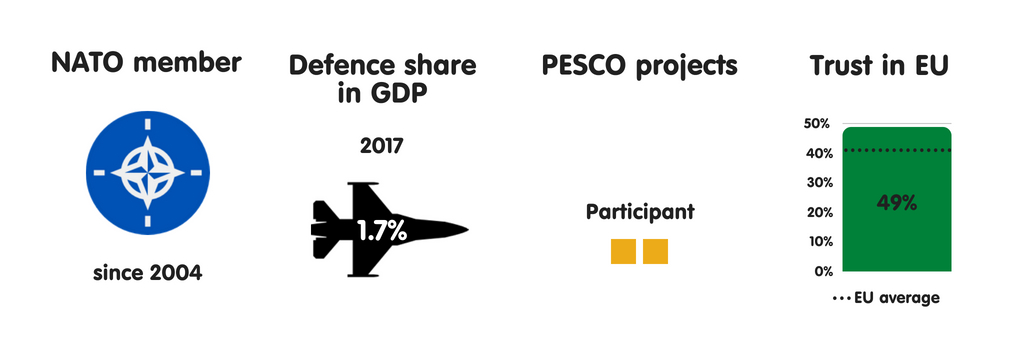

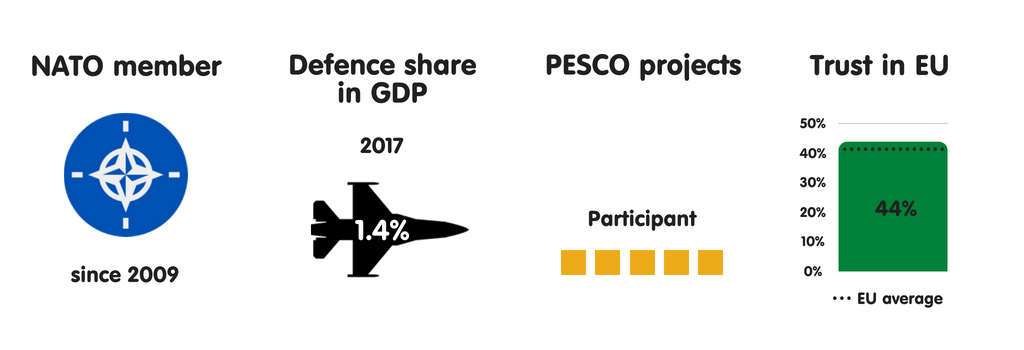

ESTONIA

What does the country fear?

Estonia is one of two EU member states that see external meddling in domestic politics as its most significant security threat (the other is Lithuania). Estonia also sees the deterioration of the rules-based international order and – given the country’s dependence on information technology – cyber attacks as major threats. Estonians expect external meddling in domestic politics to remain a leading security threat in the next decade, although they suspect that issues such as economic instability and uncontrolled migration will also become important.

Who does the country fear?

Estonia has long seen the Russian government as far more of a threat to its security than any other actor. It expects this to remain the case during the next decade. Estonia also views North Korea as a significant threat, mostly due to Pyongyang’s capacity to destabilise Europe. Estonians believe that powers such as China and Turkey – and even the United States – may increasingly come to be threats in the next decade.

Essential security partners

Estonia’s most important European security partners are other NATO members, especially the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Poland. Nonetheless, the US continues to be Estonia’s crucial security partner, contributing to its security through the deployment of troops, missile-defence radars, and other materiel on Estonian soil, as well as technological cooperation, high-level political coordination, and technical military and intelligence collaboration. Tallinn believes that it may have to make concessions to the Trump administration to ensure that the US remains engaged with European security.

The EU as a security actor

Like their counterparts in most other EU countries, the Estonian establishment largely perceives the EU as a transatlantic geopolitical project that has NATO as its backbone. Yet Estonia is also one of two EU countries that see PESCO as an essential initiative that could significantly contribute to national security (the other is Luxembourg). Estonia is particularly interested in establishing a so-called “military Schengen Area”, which would help EU member states’ military units pass through one another’s territory. The Estonian establishment views efforts to strengthen defence industry cooperation within the EU as primarily a way to enhance European defence cooperation more broadly – rather than as an economic opportunity or threat.

FINLAND

What does the country fear?

Finland perceives the most significant threats to its security as being inter-state war, cyber attacks, and external meddling in domestic politics. It is one of eight EU countries that consider there to be a significant risk of an inter-state war (the others are Greece, Cyprus, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, France, and the United Kingdom). According to the Finnish government, following Russia’s operations in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, “the early-warning period for military crises has shortened and the threshold for using military force has become lower”, leading to a situation where “the use or threat of military force against Finland cannot be excluded”. However, Finland perceives the main threat to its security as being a mixture of military and non-military “hybrid influencing” activities, which include cyber and information operations.

Who does the country fear?

Finland key foreign, security, and defence policy assessments portray Russia as the most threatening actor it faces. One of seven EU countries to take this view (the others are Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, the UK, Germany, and Romania), Finland viewed Moscow as a threat long before the Russian occupation of Crimea and the outbreak of conflict in eastern Ukraine created instability in Europe’s security environment. Indeed, in 2008, Helsinki was deeply concerned about the Russia-Georgia war and perceived Russia’s apparent attempt to acquire the status of a great power once more. Finland sees neither China nor the United States as threats, and it maintains amicable relations with Turkey.

Essential security partners

Finland views Sweden as an essential security partner (due to their bilateral defence cooperation and joint territorial defence exercises), as it does Germany and the UK (having established framework agreements with both countries). Helsinki also views the Dutch as close partners on EU security and defence policy. Nonetheless, it perceives Washington as its most important security partner; the advent of the Trump administration has not significantly changed this. Although Finland signed a new statement of intent on defence cooperation with the US and Sweden in May 2018, Finnish politics remains divided over whether to apply for NATO membership (a split that dates back to the 1990s). Parts of the Finnish political leadership openly support the move, but most Finns oppose it.

The EU as a security actor

Regarding the EU as a form of security community, Finland strongly supports the development of EU security and defence policy, as well as European defence cooperation. Finland views the NATO presence in Europe and the US commitment to the alliance as essential to its security. Having long supported the EU’s security and defence policy, Helsinki is likely to continue to do so regardless of shifts in US politics. The Finnish government has been very supportive of PESCO, even though it has few expectations of the initiative – a stance reflected in its modest level of participation in the first round of PESCO projects.

FRANCE

What does the country fear?

France perceives terrorism and cyber attacks as the most significant threats to its security. The country’s 2017 Strategic Review also emphasised its significant concern about the deterioration of the rules-based international order, especially in the realm of non-proliferation. Unlike other large EU member states, France perceives the return of military competition and inter-state war as a genuine threat. Paris regards all these threats as having intensified in the past decade, expecting them to remain acute or even rise in the next decade. France sees itself as highly resilient against the threats it faces, particularly military attacks on its territory and disruptions in the energy supply.

Who does the country fear?

Due to the recent terrorist attacks on Paris, Nice, and other parts of France, the French government sees jihadist groups (from Syria, Iraq, and the Sahel region, as well as Europe) as posing the most pressing threat it confronts. It also regards Russia and North Korea as significant threats. France believes that Russia is most likely to attack the EU through economic warfare, cyber operations, information warfare, and interference in domestic politics. It expects the threat from Russia to recede over the next decade but that from international criminal groups to increase in the period.

Essential security partners

Paris perceives the transatlantic relationship as important, with the United States contributing to French national security through high-level political coordination at the UN Security Council and elsewhere. France engages in technical military and intelligence cooperation with the US in expeditionary operations, including Barkhane (in the Sahel) and Chammal (in Syria and Iraq). Within the EU, France’s key security partners are the United Kingdom along with Germany, Italy, and Spain. France wants to maintain its close defence and security relationship with the UK through bilateral cooperation after Brexit. But the French military – and parts of the French political elite – fear that Brexit will weaken Paris within the Union by removing the only member state that shares much of France’s strategic culture.

The EU as a security actor

France regards the EU as a security community that should aim to develop closely interconnected – if not unified (as in President Emmanuel Macron’s proposal for a joint intervention force) – armed forces capable of operating autonomously across the globe. A leader in establishing PESCO, France sees the initiative as a significant step forward for European defence and coordination between European countries more broadly (if not as far-reaching as it originally hoped). Paris regards efforts to strengthen defence industry cooperation in the EU through the European Defence Fund as beneficial so long as they only boost European companies (rather than European subsidiaries of external companies) and enhance European strategic autonomy. Still, France’s European Intervention Initiative (EI2) stresses its focus on operations and its reliance on flexible cooperation and integration.

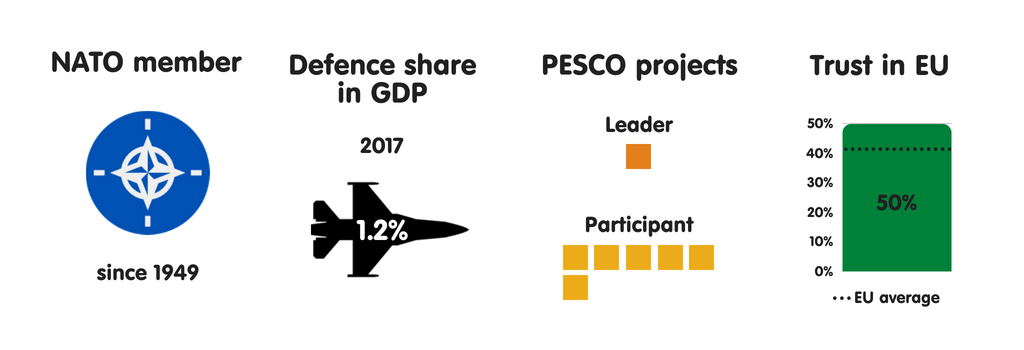

GERMANY

What does the country fear?

Despite its size, economic power, and geopolitical strength, Germany feels vulnerable to a wide variety of new and traditional threats. The government is most concerned about terrorism, a lack of state resilience, the potential for state collapse in the European Union’s neighbourhood, and the possible disintegration of the EU. It also regards cyber attacks, external meddling in domestic politics, and the deterioration of the rules-based international order as serious threats. Berlin sees uncontrolled migration, along with its root causes and effects, as the principle stability risk Europe faces. Berlin believes that all these threats have intensified since 2008.

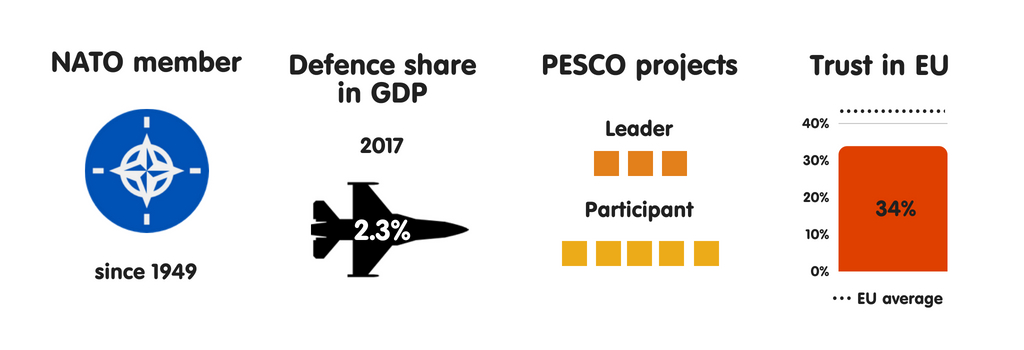

Who does the country fear?

Germany sees Russia and, to a lesser extent, China as the most threatening actors it confronts. The 2016 German White Paper on Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr states: “Russia is openly calling the European peace order into question with its willingness to use force to advance its own interests and to unilaterally redraw borders guaranteed under international law, as it has done in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. This has far-reaching implications for security in Europe and thus for the security of Germany.” The paper portrays jihadism as a “cross-cutting issue” that is highly important. Berlin perceives Iran as a potential risk due to questions around its involvement in arms proliferation and the destabilisation of the Middle East, but not as a pressing issue. Germans have also begun to regard the United States as a kind of security threat, as the unpredictability of the current US administration has created “unprecedented insecurity” in transatlantic relations.

Essential security partners

Germany views France as its most important security partner by far. The countries generally cooperate closely within an EU framework, often basing their security partnership on a shared willingness to promote the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). Germany also sees the United Kingdom as an important partner due to the latter’s military power and the cooperation between their defence industries. Berlin perceives Poland’s investment in military capacity and defence industry as important to German national security, and maintains close cooperation between the German and Dutch armed forces. For Germany, the US security guarantee and cooperation within NATO are crucial. The government has significantly upgraded its engagement within NATO in reaction to instability in Europe’s neighbourhood. However, due to the growing risk that the US security guarantee will lose its credibility, German leaders largely agree that they need to enhance and modernise national defence capabilities while also promoting closer CSDP cooperation.

The EU as a security actor

The German government is hugely supportive of EU security and defence integration, believing that it is central to German security. In a speech to the Munich Security Conference in February 2018, German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen stated: “We want to stay transatlantic – and at the same time become more European. It is about a Europe that can mobilize more military weight; that is more independent and can assume more responsibility – in the end, also in NATO.” The German government’s coalition treaty states: “We will fill the European Defence Union with life. This implies advancing the PESCO projects and the use of the newly established European Defence Fund.” Yet German officials acknowledge that there has been little progress on European defence integration, and that the process is as much about the integrity of the broader European project as it is about security.

GREECE

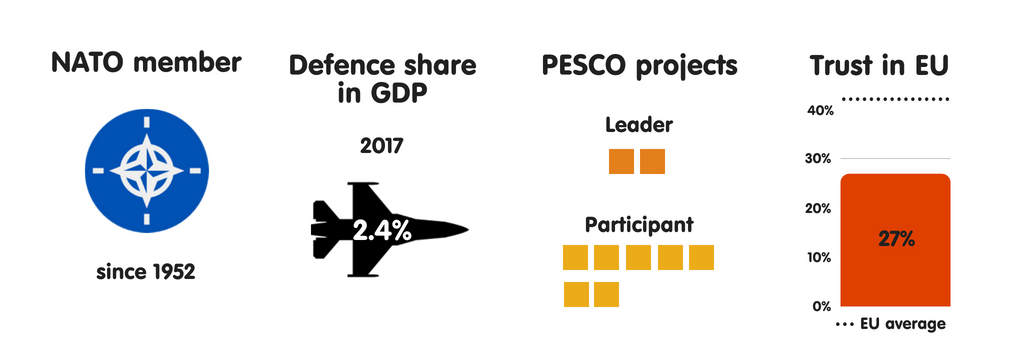

What does the country fear?

As it prepares to end its third financial bailout programme, Greece continues to see economic instability as one of the top threats to its security. It is equally concerned about inter-state war, uncontrolled migration, and terrorist attacks (among other EU countries, only Poland sees inter-state war as top threat).

Who does the country fear?

Athens’ concern about inter-state war and migration relates to the erosion of Turkish democracy under Recep Tayyip Erdogan: Greeks fear not just his neo-Ottoman regional aspirations but also his ambivalence to the EU-Turkey refugee agreement. Greece perceives Turkey as the most threatening actor it faces, despite the fact that they are both members of NATO (among other EU countries, only Cyprus and Bulgaria regard Turkey as at least a significant threat). There is greater tension between Athens and Ankara than at any time since 2003, when Erdogan came to power. Turkish policies on the Aegean Sea and Cyprus’s exclusive economic zone have caused alarm among Greeks, prompting Athens to look for new defences against potential Turkish aggression. The Greek government also sees international criminal organisations and jihadists as major threats, fearing that these actors will enter Greece from Turkey by using the refugee crisis as cover. Athens does not view China or Russia as threats (although Russia is a divisive issue in Greek politics).

Essential security partners

Greece sees France and Germany as its most important European security partners, having bought military equipment from both countries. Athens believes that Paris supports its views on Turkey, and that it can count on Germany to restrain Erdogan’s regional ambitions. Greece also closely cooperates with Cyprus and Italy, often joining them in military exercises that involve Israel and the United States as well. Viewing Washington as its key non-European security partner, Greece expects the US to upgrade a military base in Crete, partly in response to Turkey’s perceived unreliability as a NATO member. Greece prioritises security cooperation with the US as a hedge against potential Turkish aggression, engaging in efforts such as the modernisation of F-16 fighters, and diplomacy to discourage military deals between Washington and Ankara.

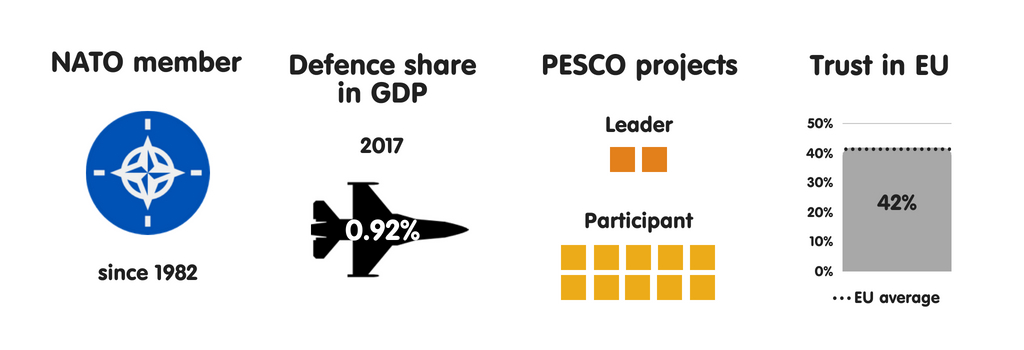

The EU as a security actor

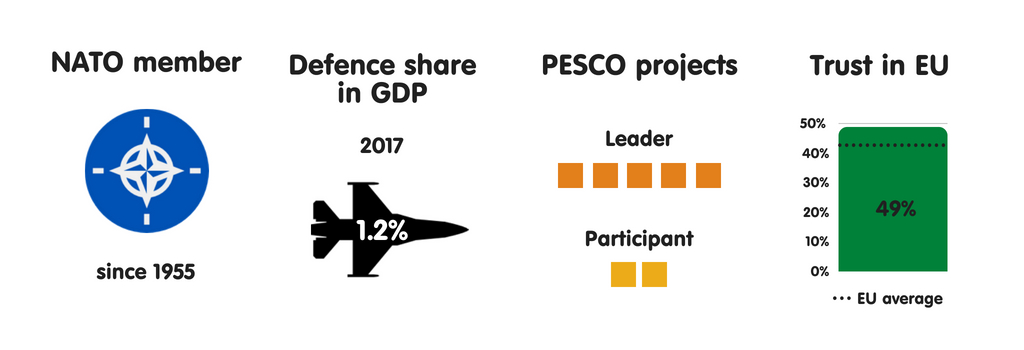

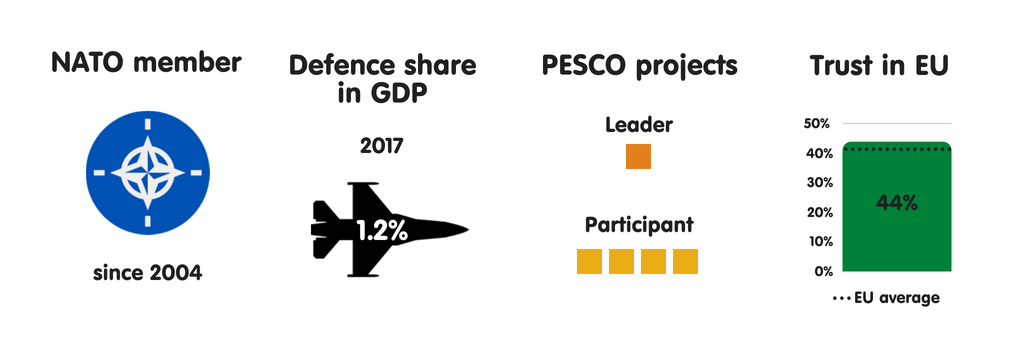

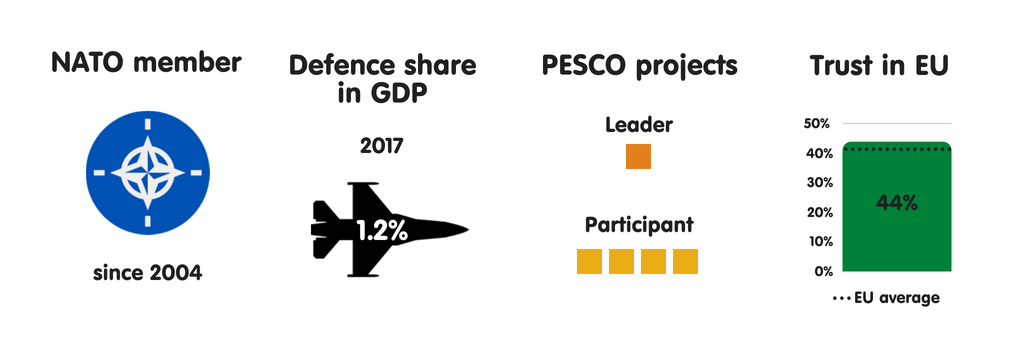

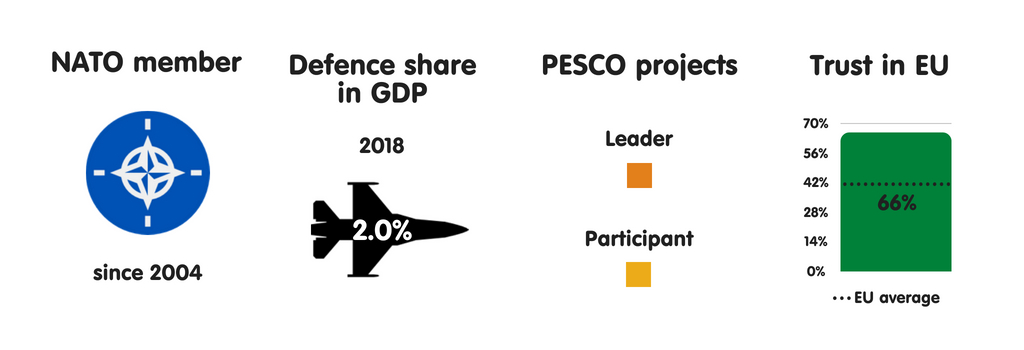

Like their counterparts in most other EU countries, Greek elites largely view the European Union a transatlantic geopolitical project that has NATO as its backbone. They believe that the EU can provide little protection against the threats they perceive as linked to Turkey and, therefore, heavily rely on the US and NATO. Although Greece has the lowest trust in the EU of any member state, it supports EU security and defence cooperation (as seen in its leadership of two PESCO projects) so long as it remains inclusive and poses no challenge to NATO.

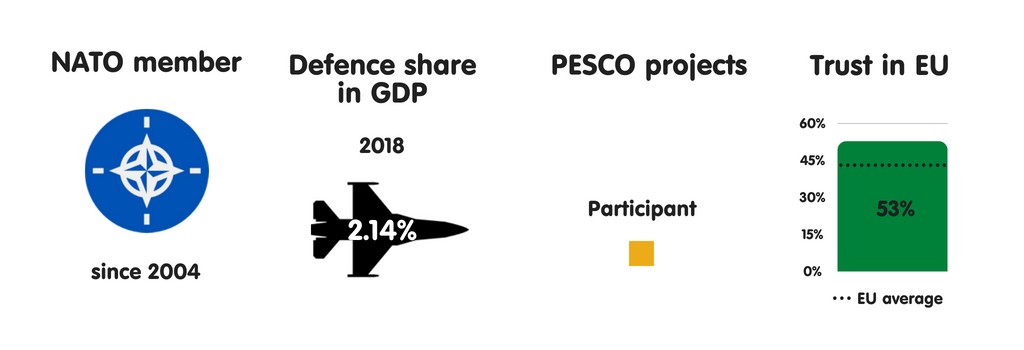

HUNGARY

Go back to the list of member states What does the country fear?

What does the country fear?

What does the country fear?

What does the country fear?

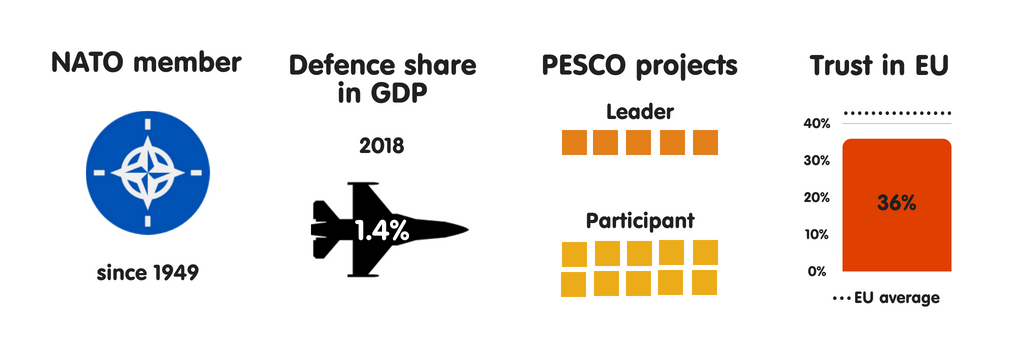

Due to the movement of large numbers of refugees and other migrants through Hungary in 2015, Hungarian leaders perceive uncontrolled migration as one of the most significant threats to national security. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán often links migrants and refugees to Islam and terrorism. Hungary also perceives major threats from: cyber attacks; terrorism; disruptions in the energy supply (the country depends on the transit of Russian gas through pipelines in Ukraine); state collapse or civil war in the European Union’s neighbourhood (particularly Ukraine); and external meddling in domestic politics.

Who does the country fear?

Hungarian leaders see jihadists and international criminal organisations as the most threatening actors it faces. The Hungarian government is particularly concerned about instability in the Middle East and north Africa, and the effects this has on migration flows to Europe. Hungary is one of five EU members that do not consider Russia to be a threat (the others are Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Portugal). Nonetheless, there are fundamental differences on this issue across the political spectrum: left-leaning Hungarian parties see Russia as a threat and criticise Orbán for strengthening ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin. They oppose the expansion of the Paks nuclear plant, fearing that the project will leave Hungary in Russia’s debt. Unlike other EU countries, Hungary is most concerned that the EU and its supporters – rather than Russia or China – will meddle in its domestic politics. Investor George Soros has become the government’s chief adversary in this, as he has clashed with Orbán on issues ranging from migration policy to the rule of law.

Essential security partners

Budapest views Berlin as its most important European security partner. This is due to Germany’s leading role in EU and NATO, as well as its historically close ties with countries in central Europe. Hungary has engaged in extensive military cooperation with Italy, focused on land forces, in the past two decades. Having cooperated within the Visegrád group, Hungary and Poland are close security partners despite their radically different perceptions of the Russian threat. Budapest also sees Vienna as a crucial partner within a central European defence cooperation group that is preparing a joint project for the next round of PESCO. Hungary views the United States as its crucial non-European ally due to the latter’s importance within NATO. American troops are deployed to the Strategic Airlift Capability in Pápa and the NATO Force Integration Unit in Székesfehérvár. However, Hungary’s relations with the US have deteriorated under Orbán.

The EU as a security actor

Having centred its security and defence policy on NATO, Hungary is unenthusiastic about European defence integration, fearing that this will compete with the alliance. Following Donald Trump’s election as US president, Hungary announced that it would spend 2 percent of GDP on defence by 2024, two years earlier than originally planned. While Orbán’s government opposed the deep and narrow version of PESCO that France favours, it welcomed the German-backed broad and inclusive version of the initiative that eventually prevailed. Hungary hopes that PESCO will strengthen European security and defence cooperation, as well as European security capabilities – not least because it believes that the EU should address the refugee crisis by defending its borders.

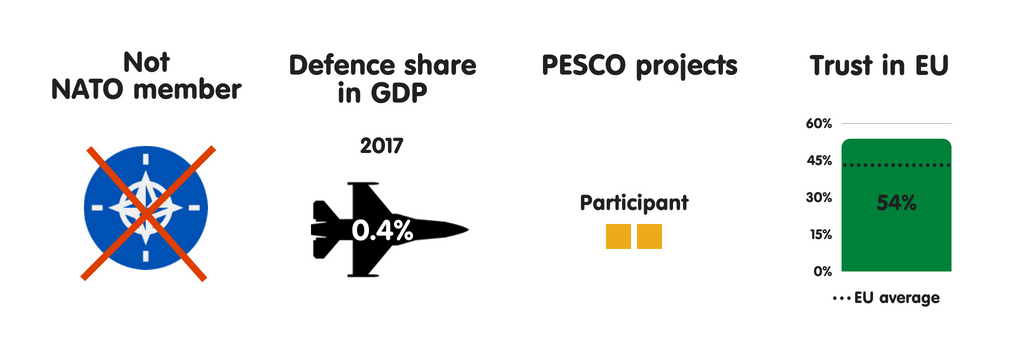

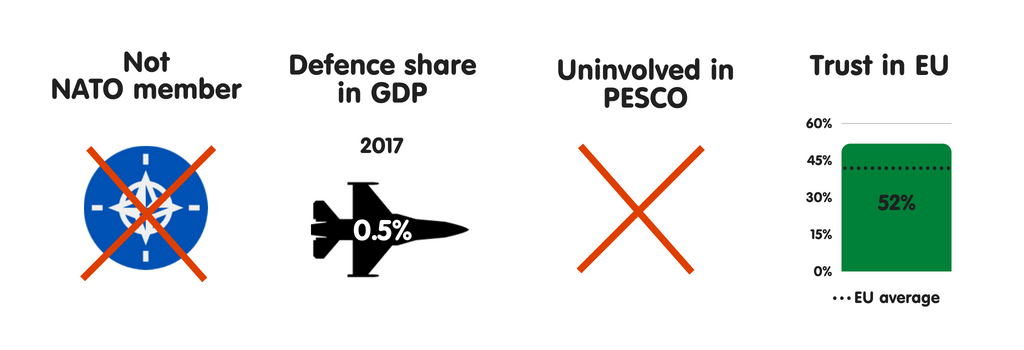

IRELAND

Go back to the list of member states What does the country fear?

What does the country fear?

What does the country fear?

What does the country fear?

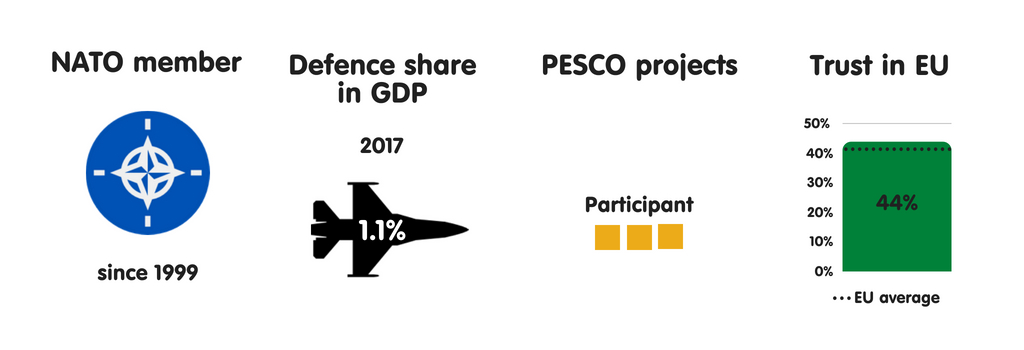

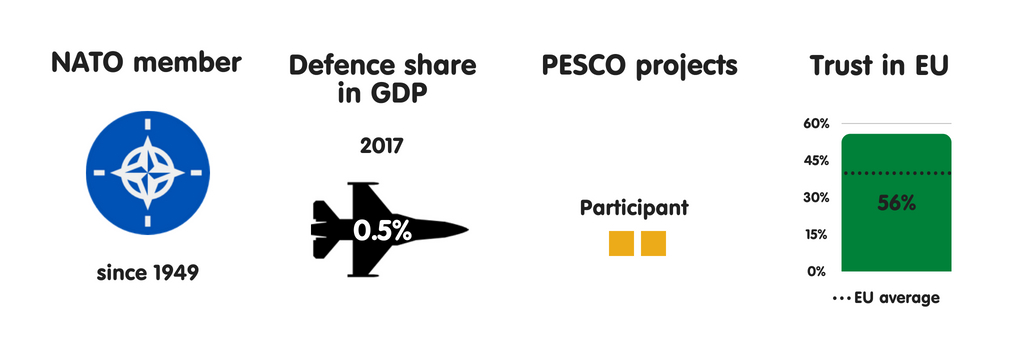

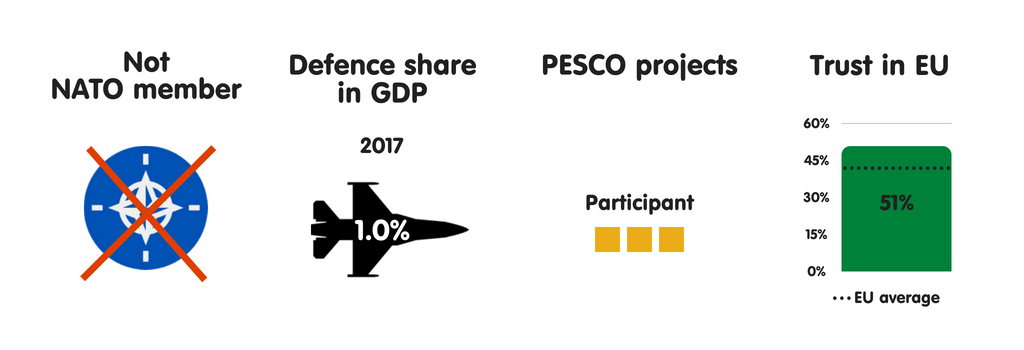

Ireland is very concerned that Brexit will exacerbate the other national security threats it confronts, particularly that from terrorism. It has remained relatively remote from the migration crisis and does not take part in the EU’s common border control and visa provisions. Therefore, Ireland does not see uncontrolled migration as a threat to national security.

Who does the country fear?

Dublin perceives the terrorism threat primarily in unionist and republican paramilitary organisations that reject the Good Friday Agreement, and that may become more active if the UK and the European Union impose controls on their border after Brexit. The Irish government also worries about a growing threat from homegrown jihadists, including those returning home after fighting in foreign conflicts. Nonetheless, Ireland does not see itself as an obvious target of aggression. Although Dublin is concerned about the Trump administration’s policies and rhetoric, it views them as having no direct impact on Irish national security. Governing party Fine Gael and the main opposition, Fianna Fail, view Russia as a moderate threat and are pro-EU and pro-NATO. Sinn Fein, Ireland’s third largest party, does not see Russia as an inherent threat, positioning itself as anti-war, anti-NATO, and anti-PESCO.

Essential security partners

The United Kingdom is Ireland’s most important security partner in Europe, as the two countries share a border and a common travel area, operate shared watchlists, and engage in a wide range of security and justice cooperation. Ireland’s other important partners in Europe include Belgium, France, and Germany, given their shared interest in tackling homegrown terrorism. Dublin sees the countries’ experiences in this area as instructive, and engages in intelligence sharing with them. Although it does not officially depend on the US security guarantee, Ireland has long benefited from American engagement with European security. Ireland engages in intelligence sharing with the United States, perceiving exchanges on cyber security as particularly important.

The EU as a security actor

Irish leaders support PESCO, seeing it as beneficial for national security not just in defence cooperation but also in strengthening the EU following Brexit. Because it spends little on defence, Ireland believes that the initiative could help it draw funding for research and capacity building, enhancing its defence forces’ training, equipment, and information sharing capabilities. Some Irish leaders have criticised PESCO’s impact on Ireland’s neutrality. However, PESCO does not alter the fact that Irish troops will only be deployed abroad with government approval, the endorsement of parliament, and UN authorisation.

ITALY

What does the country fear?