Parag Khanna

The 20th century, however, witnessed the succession of Japanese imperialism, decolonisation, multilateralism and cold war proxy competition, all of which have left an indelible mark on East Asia’s patterns of interaction.

The 20th century, however, witnessed the succession of Japanese imperialism, decolonisation, multilateralism and cold war proxy competition, all of which have left an indelible mark on East Asia’s patterns of interaction.

The confluence of these legacies forms the complex backdrop to disputes such as the South China Sea, where pre-colonial coexistence has morphed into intricate military and legal manoeuvring to exclusively demarcate what for most of history has been shared.

Amid the current military escalations and adversarial legalism clouding the maritime domain, how can the South China Sea disputeS be settled using modern tools of statecraft while reviving the region’s ancient spirit of mutuality?

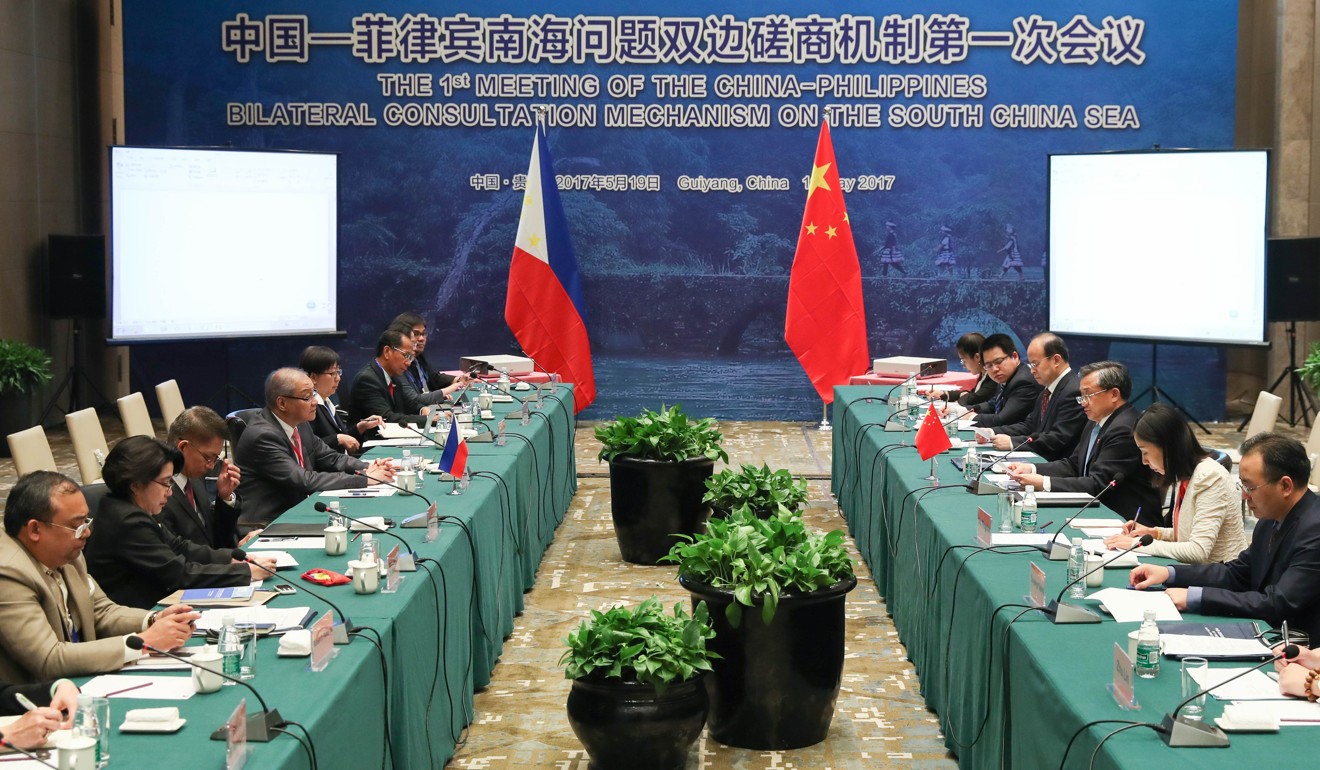

Recent years have witnessed a heightened sense of urgency around the South China Sea, both due to escalating commercial and military activity as well as a flurry of diplomatic proceedings.

Watch: China redeploys missile systems on South China Sea island

Regional governments have assembled and issued statements calling for cooperation towards peace and prosperity and avoiding confrontation by shelving sovereignty disputes. But sovereignty disputes are not solved by being put off. They are settled through creative arbitration that finds a lasting solution agreeable and even beneficial to all parties.

Sovereignty disputes are not solved by being put off. They are settled through creative arbitration

Current dynamics do not live up to this ambition. China’s approach has been a de facto unilateralism, fortifying rocks into islands serving as forward operating bases for military patrols and commercial fishing. While this reflects obvious power dynamics in the region, it also engenders insecurity, suspicion and counter-manoeuvres inimical to Chinese interests.

The Philippine approach has been a defensive legalism, appealing to The Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration, which ruled against China’s expansive “nine-dash line” claims, its island reclamation activities and its illegal fishing in Philippine waters. While these findings provide diplomatic guidance by reinforcing the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, they are legally non-binding and thus of limited utility in conflict resolution.

The regional approach (such as via the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) has been to pursue a code of conduct to prevent incidents and build trust and confidence. While this pragmatic attitude is welcome, the result is more a normative framework rather than a legally binding settlement.

Lastly, the Western approach has been to assert multipolarity through freedom of navigation operations involving the navies of the United States, Britain, France, Japan, Vietnam and others.

While these exercises signal the importance of openness and non-exclusivity of the waters, they raise the risk of inadvertent conflict in what should be a purely commercial domain.

Watch: US Navy continues South China Sea patrols despite Beijing’s protests

Overall, while all parties pledge pragmatism over intransigence, the collective outcome has been that each party is locked into its own approach, leaving little scope for consensus.

There is promise, however, in calls to share (with equal participation) rather than monopolise the rich hydrocarbon, fishery and seabed resources of the South China Sea. For China, this represents conceding that the waters cannot be exclusively controlled.

At the same time, what China might gain in return is recognition of its claims that pertain to the 12 largest Spratly Islands, giving it the requisite 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone towards the open sea while observing the equidistance line towards nearby coasts of other claimant states such as the Philippines.

At the same time, what China might gain in return is recognition of its claims that pertain to the 12 largest Spratly Islands, giving it the requisite 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone towards the open sea while observing the equidistance line towards nearby coasts of other claimant states such as the Philippines.

By this logic, calls for joint development have been premature. Many have offered joint zonal development as an alternative to settling sovereignty, but boundary agreements are rarely perceived as fair by both parties.

Malaysia and Thailand, and Thailand and Vietnam, have adopted joint development zones, but their territorial disputes had already been effectively resolved.

A new arbitration process, equal parts political and legal, could bring about the necessary mediation, facilitation and binding resolution mechanism needed to move from militarised dispute to boundary settlement to joint development. A panel of commissioners comprised of delegates from the six claimant states plus a number of independent members would be given a time-bound mandate to produce a comprehensive solution.

Earlier this year, Australia and East Timor accepted a package of proposals offered by a five-person commission that provided for maritime boundary delineation and revenue-sharing from a large gas field straddling their respective territories. Given its recent history of hosting high-level summits and the opening of an office of The Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration, Singapore would be a logical choice of venue for the one-year proceedings.

Earlier this year, Australia and East Timor accepted a package of proposals offered by a five-person commission that provided for maritime boundary delineation and revenue-sharing from a large gas field straddling their respective territories. Given its recent history of hosting high-level summits and the opening of an office of The Hague Permanent Court of Arbitration, Singapore would be a logical choice of venue for the one-year proceedings.

For both the Philippines and Vietnam, political compromise with China could put them in a strategic comfort zone from their current position of caving to Chinese intimidation. The Rodrigo Duterte government lacks the capacity to stand up to China and has awkward relations with its long-time ally the US, while conciliation with China would be rewarded by lucrative oil contracts and access to capital and partnerships in new areas such as seabed mining.

Vietnam, whose dispute with China over the Paracel (Hoang Sa/Xisha) Islands has witnessed face-offs over Chinese drilling and the cancellation of a joint PetroVietnam project with Spanish firm Repsol. In the context of a grand security and commercial bargain, both China and Vietnam could agree to accept the current de facto demarcation arrangements but only conduct commercialisation jointly in formerly disputed blocks.

A sequence such as this would bode well for pursuing other joint priorities such as fisheries conservation and environmental protection, disaster relief and humanitarian assistance, and counter-piracy patrols.

If East Asia’s growing economies and vibrant societies can demonstrate the diplomatic maturity to accept the realities of the present, they have the potential to resurrect a golden age of inter-civilisational harmony.

No comments:

Post a Comment