SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

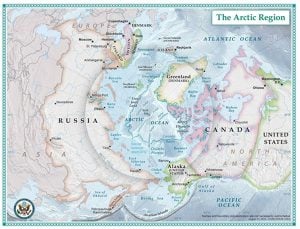

STIMSON CENTER: China and Russia are working together ever more closely in the Arctic, exploiting a policy vacuum in the US, an international panel of experts said here. But Sino-Russian cooperation is almost entirely commercial, focused on trade routes, offshore oil, telecommunications (most satellites don’t cover the Arctic), and tourism. A military alliance is unlikely given Russia’s deep ambivalence about China’s growing influence in general and their very different views on who should run the Arctic in particular: the eight circumpolar countries alone — including both Russia and the US — or a larger group that includes self-declared “near-Arctic” nations like China.

STIMSON CENTER: China and Russia are working together ever more closely in the Arctic, exploiting a policy vacuum in the US, an international panel of experts said here. But Sino-Russian cooperation is almost entirely commercial, focused on trade routes, offshore oil, telecommunications (most satellites don’t cover the Arctic), and tourism. A military alliance is unlikely given Russia’s deep ambivalence about China’s growing influence in general and their very different views on who should run the Arctic in particular: the eight circumpolar countries alone — including both Russia and the US — or a larger group that includes self-declared “near-Arctic” nations like China.

State Department map

There’s no question that Chinese activity in the Arctic has increased dramatically, both in concert with Russia and unilaterally. China sent occasionalexpeditions to the Arctic as early as 1999, said Stimson’s China program director, Sun Yun, but the pace keeps increasing: “In 2017, there were five.” Most of these voyages explored the so-called Northwest Passage from the Pacific to the Atlantic via Canadian waters, now made navigable by melting ice. But one crossed the Arctic through Russian waters, known as the Northern Sea Route, followed by Chinese commercial ships.

There’s no question that Chinese activity in the Arctic has increased dramatically, both in concert with Russia and unilaterally. China sent occasionalexpeditions to the Arctic as early as 1999, said Stimson’s China program director, Sun Yun, but the pace keeps increasing: “In 2017, there were five.” Most of these voyages explored the so-called Northwest Passage from the Pacific to the Atlantic via Canadian waters, now made navigable by melting ice. But one crossed the Arctic through Russian waters, known as the Northern Sea Route, followed by Chinese commercial ships.

Beijing sees a chance to shorten trade routes to Europe by nine to 15 days, saving millions on fuel and fees for the Suez and Panama Canals, Sun said at a Stimson Center panel in June. Global warming hasn’t yet melted enough ice to make this shortcut routine, but Chinese hopes rise with the temperature.

The Chinese may be overly optimistic, argued Russian expert Alexander Sergunin of Saint Petersburg State University. It’s “naïve” to imagine the Northern Sea Route — either past Siberia or straight over the Pole — will ever be easy, he said, despite the “hype” coming from the Kremlin. “It’ll mostly remain a Russian national maritime route” for domestic shipping, Sergunin said. “If you have ice you can struggle with it with icebreakers, but if ice breaks, it’s even more dangerous for navigation than just thick ice” in a single unbroken sheet. (The Titanic found this out the hard way). Vessels navigating the Arctic need to either have ice-hardened hulls — which are expensive — or icebreaker escort — for which the Russians demand high fees. That said, the Russians and Chinese reached a compromise in recent years: non-hardened Chinese vessels would still have to hire Russian icebreakers, but at reduced rates.

US Coast Guard graphic

Another obstacle that raises both practical and political issues is the lack of infrastructure in the far north. Both countries are interested in Chinese investment and technology to build up Russian port cities, offshore oil rigs, and, particularly, export terminals for Siberian Liquid Natural Gas, with five ice-hardened LNG carriersalready in service. The Kremlin is less enthused about the Chinese getting their hands on Russian technology, a constant problem in military sales of things like fighter jets. Russians are even more reluctant about an influx of Chinese workers, a standard feature of Beijing’s investments in the Third World but even more unsettling to Russia given its high unemployment, shrinking population, and racially tinged fears that Oriental hordes will somehow take over Siberia. (Protip: Chinese people are no more eager to live in Siberia than Russians are).

Russian and Chinese border guards push and shout at each during rising tensions in 1969

It’s worth noting that both Tsarist and Communist Russians fought with China over Central Asian territory, the latest in 1969. By contrast, the US has fought China only twice — the Peking expedition in 1900 and the Korean War in 1950-1953 — and Russia never. Russia and China see strategic advantage in cooperating both in the Arctic and against the US worldwide, but they both bring heavy baggage to the relationship.

It’s worth noting that both Tsarist and Communist Russians fought with China over Central Asian territory, the latest in 1969. By contrast, the US has fought China only twice — the Peking expedition in 1900 and the Korean War in 1950-1953 — and Russia never. Russia and China see strategic advantage in cooperating both in the Arctic and against the US worldwide, but they both bring heavy baggage to the relationship.

On the other hand, the US has been largely AWOL in the Arctic under Trump, reversing a tentative increase in attention under Obama. The chief surviving initiative is building a $1 billion heavy (and potentially armed) icebreaker for the US Coast Guard, the first of three to six such vessels. But between the Trump administration’s slowness naming key officials and its general impatience with cumbersome, consensus-driven international fora like the Arctic Council, no one at high levels is paying attention, and mid-grade bureaucrats can only do so much.

“President Trump, since he came into office almost two years ago, hasn’t really said anything about the Arctic yet, and there’s no strategy on the Arctic from his administration, although he hasn’t cancelled the previous strategy,” said George Washington University scholar Robert Orttung. The US and China actually have plenty of reason to work together in the Arctic, he said — the Chinese are particularly interested in Alaska for both energy and tourism — but the Washington is unable to engage Beijing the way that Moscow has.

“This is…the best time for Sino-Russian relations for a very long time,” Sun Yen said. But it’s “alignment rather than alliance,” she said, with many points of difference as well as agreement, on the Arctic as on other areas. For instance, Beijing is quietly unhappy with the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine, which it fears sets precedent for ethnically motivated interventions elsewhere, she said. Nor has China supported Russia’s extensive claims to circumpolar waters.

Indeed, the two nations diverge on the fundamental question of who makes international law in the Arctic. For a long time, admittedly, China wasn’t interested: Way back in 1925, the Nationalist government signed the critical Spitsbergen Treaty granting non-Arctic nations rights in the northern seas, Sun said, but his Communist successors didn’t actually realize they’d inherited those rights until 1991, “a pleasant surprise.” In the ’90s, however, the eight Arctic Council nations — the US, Canada, Iceland, Finland, Russia, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, which owns Greenland — set up a system of governance that largely sidelined other states. 13 countries do rate observer status on the Council, including China as of 2013 (even stranger bedfellows include Italy, India, and Singapore). But the eight voting members are generally not keen on diluting their control.

China, by contrast, sees itself as a rising global superpower with commensurate influence everywhere on earth. It declared itself a near-Arctic state in January — a term actually coined by Great Britain but not widely recognized. China wants non-Arctic nations, especially “near-Arctic” ones, to have greater influence and more rights in the Arctic, with binding international law based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) rather than the current patchwork of mostly voluntary regional arrangements. Indeed, said Sun, “what they would like to argue is the format and the content of the Arctic governance system currently is not effective.”

Naturally the Russians, US, Canada, and Nordics disagree. “The Arctic states would argue there is very little governance gap,” said Norway-based expert Elana Wilson Rowe, as they did in 2008 when they rejected an Antarctica-style treaty regime. Though the key agreements up north are admittedly non-binding, she said, the Arctic has become “a fairly heavily governed landscape.”

All these legal questions are largely moot, of course, if the ice doesn’t met enough that ships can sail the Arctic Ocean easily. The extent of global warming, and thus of ice melting, is still hard to predict.

So are Chinese ambitions racing ahead of Arctic realities? “It seems the chickens are being counted before the eggs are hatched,” Sun admitted, “but the Chineseposition is, ‘if the eggs are going to hatch, we want to make sure we’re there to collect the chickens.'”

No comments:

Post a Comment