This month’s inauguration of a fibreoptic cable linking Pakistan with China could prove to be a double-edged sword. Constructed by Chinese conglomerate Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd, the cable is likely to enhance both Pakistan’s information communication technology infrastructure as well as the influence of Chinese authoritarianism at a moment that basic freedoms in Pakistan are on the defensive.

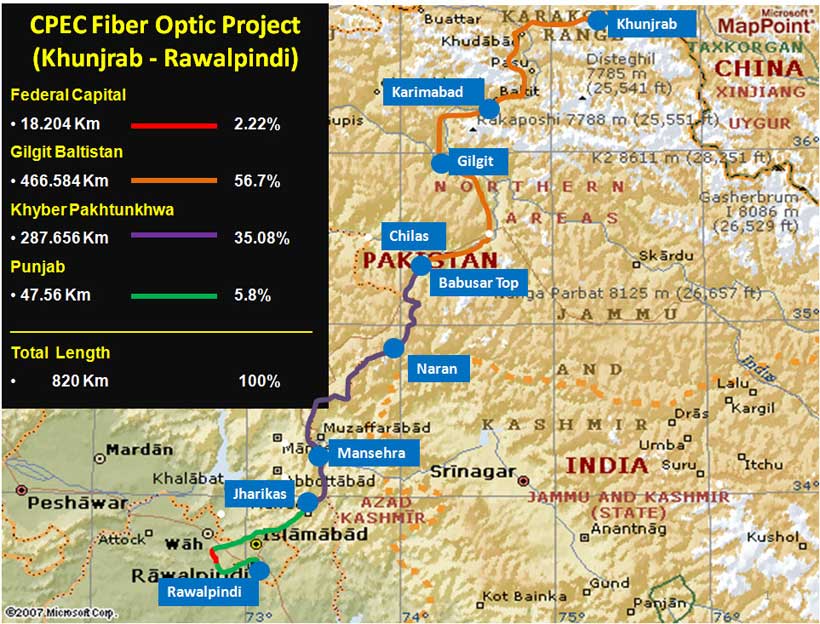

The $44 million, 820-kilometre underground Pak-China Fibre Optic Cable links Rawalpindi with the Chinese border at Khunjerab Pass and is backed up by a 172-kilometre aerial cable. A second phase of the project is likely to connect to the port of Gwadar in Balochistan, a key node in China’s US$ 50 billion plus infrastructure-driven investment in the South Asian state, dubbed the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

The cable is expected to provide terrestrial links to Iran and Pakistan and serve as a conduit to the Middle East, Europe and Africa through hook ups with submarine cables.

The inauguration of the cable came days after China launched two satellites for Pakistanfrom the Jiuquan Space Center in Inner Mongolia, to provide remote sensing data for CPEC.

The satellites are expected to monitor natural resources, environmental protection, disaster management and emergency response, crop yield estimation, urban planning and provide CPEC-related remote sensing information.

The prominence of Pakistani military officers, including General Qamar Bajwa, Pakistan’s top military commander and Major General Amir Azeem Bajwa, the head of the Special Communications Organisation (SCO), at the inauguration underlined the cable’s strategic and potentially political importance.

Pakistan’s military sees the cable as a way of ensuring that the country’s in and outbound traffic does not traverse India. Major General Bajwa told lawmakers last year that the current “network which brings internet traffic into Pakistan through submarine cables has been developed by a consortium that has Indian companies either as partners or shareholders, which is a serious security concern.”

The key to the cable’s potential political significance lies buried in the Chinese-Pakistani vision that underlines CPEC against the backdrop of Chinese concern about the messiness of Pakistani politics and the People’s Republic’s support of what it sees as the behind-the-scenes stabilizing role of the country’s powerful military.

A leaked draft outline of the vision identified as risks to CPEC “Pakistani politics, such as competing parties, religion, tribes, terrorists, and Western intervention” as well as security. “The security situation is the worst in recent years,” the outline said.

The vision appears to suggest addressing security primarily through stepped up surveillance based on the model of a 21st century Orwellian surveillance state in parts, if not all of China, rather than policies targeting root causes and appears to question the vibrancy of a system in which competition between parties and interest groups is the name of the game.

The draft linked the fibreoptic cable to the terrestrial distribution of broadcast media that would cooperate with their Chinese counterparts in the “dissemination of Chinese culture.” The plan described the backbone as a “cultural transmission carrier” that would serve to “further enhance mutual understanding between the two peoples and the traditional friendship between the two countries.”

Pakistan’s Ministry for Planning, Development, and Reform said at the time that the draft “delineates the aspirations of both parties”

The cable’s facilitation of aspects of the Chinese surveillance state and soft power strategy occurs in a country in which feudal and patronage politics dominate the countryside and the military has sought to severely curb media coverage in the run-up to elections scheduled for July 25.

“Democracy has become a terrifying business in the villages of Pakistan. Elections might change the federal and state governments, but the feudal and punitive power structures in the countryside don’t change. The feudal lords offer allegiance to the new ruler and continue to oppress the poor villagers,” said Ali Akbar Natiq, a scholar, poet and novelist who returns every two weeks to his home district of Okara in Punjab, in an article in The New York Times.

The media crackdown involves censorship of TV channels, newspapers and social media, including preventing the distribution of Dawn. An English-language newspaper, Dawn was established by Pakistan’s founder Mohammed Ali Jinnah before the 1947 partition of British India, as a way for Muslims to communicate with the colonial power.

Cable operators were advised to take Dawn’s TV channel off air, advertisers were warned to shy away from the paper while its journalists were harassed. Other journalists and media personalities have been kidnapped or detained by masked men believed to be linked to military intelligence.

Columnist and scholar S. Akbar Zaid said last month that he was advised by Dawn that the paper could no longer publish his column “because of censorship problems that they are facing with regard to the military and its agencies. They say that the threats are very serious,” Mr. Zaid said.

Daily Times journalist Marvi Sirmed reported that her home was burgled and ransackedlast month. The intruders took her computers, smartphone, and her passport as well as those of members of her family but left valuables such as jewellery untouched.

Pakistan’s military has denied cracking down on the media although it conceded that it was monitoring social media.

Bloggers, including well-known journalist Gul Bukhari, are among those who have been detained and released in some cases only weeks later.

A guard in a detention centre where five bloggers were held last year for three weeks, alongside ultra-conservative militants, told his captives:, according to one of the detainees: “You are more dangerous than these terrorists. They kill 50 or 100 people in a single blast, you kill 600,000 people a day,” a reference to the 600,000 clicks on the bloggers’ Facebook page on peak days.

In an editorial published after months of harassment Dawn charged that “It appears that elements within or sections of the state do not believe they have a duty to uphold the Constitution and the freedoms it guarantees. Article 19 of the Constitution is explicit: ‘Every citizen shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression, and there shall be freedom of the press.’ The ‘reasonable restrictions’ that Article 19 permits are well understood by a free and responsible media and have been consistently interpreted by the superior judiciary.”

The paper went on to say that Dawn “considers itself accountable to its readers and fully submits itself to the law and Constitution. It welcomes dialogue with all state institutions. But it cannot be expected to abandon its commitment to practising free and fair journalism. Nor can Dawn accept its staff being exposed to threats of physical harm.”

At the bottom line, Pakistan’s new fibreoptic cable promises to significantly enhance the country’s connectivity. The risk is that visions of Chinese-Pakistani cooperation in the absence of proper democratic checks and balances threaten in Pakistan’s current political environment to undermine the conditions that would allow it to properly capitalize on what constitutes a strategic opportunity.

No comments:

Post a Comment