By John Taishu Pitt

On May 23, 2018, legislation to reform the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) was passed in the House Financial Services Committee and the Senate Banking Committee. There has been broad bipartisan support for the proposed legislation which would reform CFIUS to expand its jurisdiction. While many support the reform to fill the gap in oversight pertaining to foreign direct investment (FDI) into important U.S. sectors, others have raised the broader concern that the increased restrictions may send the world a message that the U.S. is closed for business — especially in light of the Trump administration’s increased unilateral protectionism.

On May 23, 2018, legislation to reform the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) was passed in the House Financial Services Committee and the Senate Banking Committee. There has been broad bipartisan support for the proposed legislation which would reform CFIUS to expand its jurisdiction. While many support the reform to fill the gap in oversight pertaining to foreign direct investment (FDI) into important U.S. sectors, others have raised the broader concern that the increased restrictions may send the world a message that the U.S. is closed for business — especially in light of the Trump administration’s increased unilateral protectionism.

CFIUS is an interagency committee made up of 14 U.S. agencies that provide the president a comprehensive government perspective on merger and acquisition (M&A) regarding national security. The committee is authorized to evaluate a transaction when a foreign party is buying or otherwise acquiring “control” over a U.S. business and to provide recommendations to the president on whether or not to block the transaction on the grounds of protecting national security.

To date, only five investments have been blocked by previous presidents, according to the Treasury Department’s Annual Report to Congress regarding CFIUS. However, out of these five blocked transactions, President Donald Trump is already responsible for two of them. In 2017, Trump blocked the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corp. by the Chinese investment firm Canyon Bridge Capital Partners; in 2018, he blocked the acquisition of Qualcomm Inc. by Singapore-based Broadcom Ltd., scuttling a $117 billion deal that would have been the biggest technology deal in history. Beyond the blocked transactions that attract more media attention, there are growing numbers of deals that are quietly being withdrawn because of increasingly critical scrutiny by CFIUS, particularly of deals involving Chinese parties.

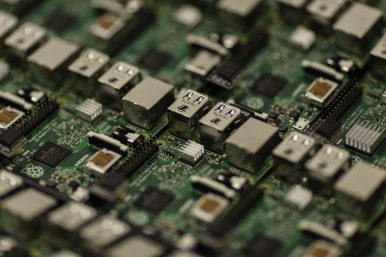

CFIUS has gained much attention with the increase of Chinese investment toward U.S. emerging technologies. Chinese leaders have been pushing policies such as the “Made in China 2025” to encourage Chinese businesses to invest overseas. Some argue that this effort by China is for commercial reasons, but some suspect that it is also for China to better equip itself for strategic competition with the United States. In recent years, Chinese companies have made multiple transactions in the areas of advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, semiconductor, and quantum computing technology. This shift has been broadly consistent with the technology roadmaps the Chinese government has designated as a particular priority.

Both House and Senate versions of the revised Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) contain provisions to define “critical technology,” which U.S. businesses had warned were too vague in previous drafts. The legislation will also expand the CFIUS’s purview to include transaction types that are not currently covered by CFIUS provisions, such as the purchase or lease of real estate near sensitive U.S. facilities, and bankruptcy liquidations. Under current law, CFIUS’s jurisdiction is triggered only when a foreign investor acquires control over a U.S. business. The new legislation will allow CFIUS a review process for incremental control. The Senate version would also prevent the president from reversing sanctions levied against the Chinese telecommunications company ZTE that conducted illicit transitions with Iran and North Korea.

It is important to note that the Senate bill was also attached as an amendment to the must-pass National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Although the Senate voted to pass the $716 billion defense policy bill on June 18, the bills would still need to be made consistent with one another and be approved by Congress. With broad bipartisan support, the bill generally appears to have few obstacles in the way of its passage. However, with the White House and some Republicans opposing the inclusion of the ZTE provision in the NDAA, it could be difficult for it to remain in the final version of the bill.

Even though much of the reform concerns China, in light of how CFIUS thinks about threat actors, it is likely that the CFIUS overhaul may have greater impact on other countries as well. For example, if a Japanese company were to have extensive unrelated operations in China, CFIUS could look at how the acquisition of a given company in the U.S. by the Japanese company — by virtue of this indirect exposure to China — would pose a national security threat. So even though much of the reform concerns China, more transactions with other countries could be impacted as well.

As the largest global investor and the largest recipient of FDI, the approach the U.S. has taken toward international investment has been to uphold the free and open rules-based system it has benefited from over the years. Even in cases where there were national security concerns, the U.S. approach has generally been to minimize the impact of the national security review process which may have had distorting effects on the market. However, some of the recent debates to reform CFIUS have focused on ways to approach dissatisfaction regarding the economic impact of FDI on the U.S. economy and potentially to use CFIUS to better economically compete with China. As in the case of the Section 232 tariffs and quotas on steel and aluminum, U.S. unilateral actions that allegedly target problematic actions by China have been mostly felt by U.S. allies. Unreasonable use of national security as a justification to protect U.S. industry could have a detrimental impact on the rules-based system the U.S. has benefited from, and will limit cooperation from our closest allies.

John Taishu Pitt (@YJTPitt) is a trade policy specialist at a law firm in Washington D.C. where he focuses on trade and security relations in East Asia.

No comments:

Post a Comment