"We’re going to turn that off unless you secured that properly. Whoa! That's a very different mindset," Col. Straub told me. "The availability of the network versus the defense of the network, that's something we’re trying to get commanders to think about.".

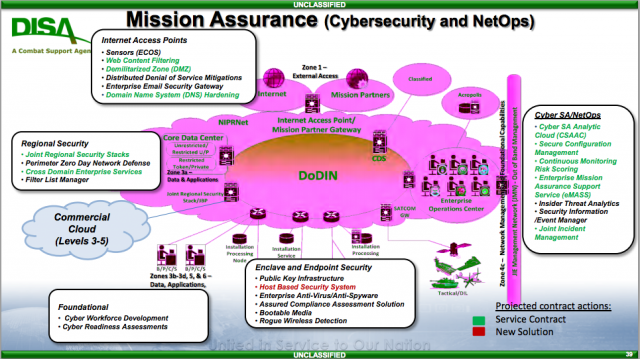

A DISA schematic of the Department of Defense Information Networks (DoDIN).

ARMY-NAVY COUNTRY CLUB, ARLINGTON: If your unit’s network is not secure, you and your fellow warriors may lose access to the wider Defense Department network until you fix it. That’s the new philosophy — not yet a formal policy — that two Defense Information Systems Agency officials laid out to the industry group AFCEAhere, just two miles from the Pentagon.

“We’re in the middle of a cultural shift,” said Col. Darlene Straub, a career Army signals officer who now heads defensive cyber operations at DISA. “We’re saying ‘no’ to things.”

For two decades of war, Straub told me after her public remarks, the imperative for communications officers like herself was to get everyone connected first — every outpost, headquarters, and agency — and worry about security second. Now, however, with ever larger quantities of increasingly vital data on the network, exposed to ever more sophisticated attacks, the calculus is changing. If an office hasn’t properly patched its software against hackers, or a unit’s position is too exposed to electronic eavesdropping, it may be necessary to disconnect them until the problem’s fixed to protect the wider network and all its users.

“What’s available on the network today is so much more damaging,” Lisa Belt, acting director of cyber development for DISA, told the AFCEA gathering. Blue Force Tracker systems report the GPS-verified position of vehicles and sometimes even individuals on foot. That’s a huge help to coordinating maneuvers and avoiding friendly fire, but it could be lethal in hostile hands. Logistics systems track vehicles’ fuel levels and when they might next need repair. That’s a huge help to supply units and maintainers, but a potential list of weak points for an adversary.

So sometimes keeping the network secure is more important than keeping it available, Belt said. Even if it’s your unit being cut off from the network, losing access temporarily may endanger you less than keeping access and letting the enemy steal your data.

“Now, it’s like, ‘we’re going to turn that off unless you secured that properly.’ Whoa! That’s a very different mindset,” Straub told me. “The availability of the network versus the defense of the network, that’s something we’re trying to get commanders to think about, and it’s something that comes into play now in the decision making.”

That may sound like an intrusion into the authority of commanders to command, but there is plenty of precedent. A commander who didn’t secure his supply lines might have trouble getting supplies, and his logistics officers might tell him they couldn’t send a convoy through for fear of getting ambushed. That’s very similar to a network officer telling the commander they can’t send him data for fear of it being hacked. Once dismissed as tech weenies — one general once said when he listened to cyber officers, it sounded like “dolphin speak” — now the nerds can say “no.”

Straub credits the recently retired chief of Cyber Command, Adm. Michael Rogers, with pushing this revolution. “We used to take a really long time to patch networks and update them….Adm. Rogers started drawing deadlines and saying, ‘if you don’t do this, we will turn you off,'” she told me. “And that’s a new concept, where a four-star is going to look at another service component and go, ‘I’m going to turn off.'”

Cloud Security and End User Responsibility

“Our biggest challenge is some of our organizational limitations,” not technology, Straub said. Though it may look monolithic, the Defense Department is actually a patchwork of tribal fiefdoms, each jealous of its independence and prerogatives. That’s manifested in a network that grew from the bottom up, with each organization wanting its own software, its own hardware, and its own server in a closet somewhere on-site. Now the Pentagon is laboriously imposing common standards and central control through agencies like DISA and Cyber Command.

“Can we get to the point where we release some of our control?” Straub asked. “Maybe the Air Force doesn’t own their network, the Army doesn’t own their network…. and then the data is easier to manage.”

“The organizational culture has to …. let go of ownership,” she said.

The atavistic organizing principle is, grab “the closest throat to choke,” said a third DISA official, chief of cloud services John Hale, at a cyber panel last month. “When you’re a commander and you want some action, you want to be able to reach and touch somebody” to make it happen. (It’s a management theory Darth Vader would be down with). As long as your network is your own little fiefdom, you know someone who works for you is responsible for making it do what you want. As soon as you give up control to a larger organization, you go from being the boss to just one customer among many.

One of the biggest ways organizations are giving up control is by going to the cloud— that is, moving data and sometimes programs from their own on-site servers to centralized servers run by outside parties like Amazon. A major attraction of cloud computing, besides lowered costs, is its potential to improve security by enforcing common standards and centralizing data. It’s a version of “put all your eggs in one basket and then watch the basket.”

But going to the cloud doesn’t mean you can relax, Hale warned. Typically, while data is stored by cloud providers that must pass Pentagon certification, he said, the programs or applications that work on that data still belong to the user, who must make sure they’re secure.

In fact, Straub said, we need to erect stronger defenses around the end user and their devices: laptops, smartphones, and the myriad chips embedded in ground vehicles, ships, aircraft, and baby monitors as part of the “Internet of Things.” That includes “continuous” verification of each user using “multiple factors,” Belt added, rather than just entering name and password once, or even swiping a CAC smart card.

This focus on the end user is a big step from traditional “boundary” defense, which focuses on keeping bad actors out of the network, or the current strategy of “defense in depth,” which looks for anomalies inside the network to catch hackers who’ve gotten in. “It flips everything upside down,” Straub said, “and that’s going to be a hard change for us.”

No comments:

Post a Comment