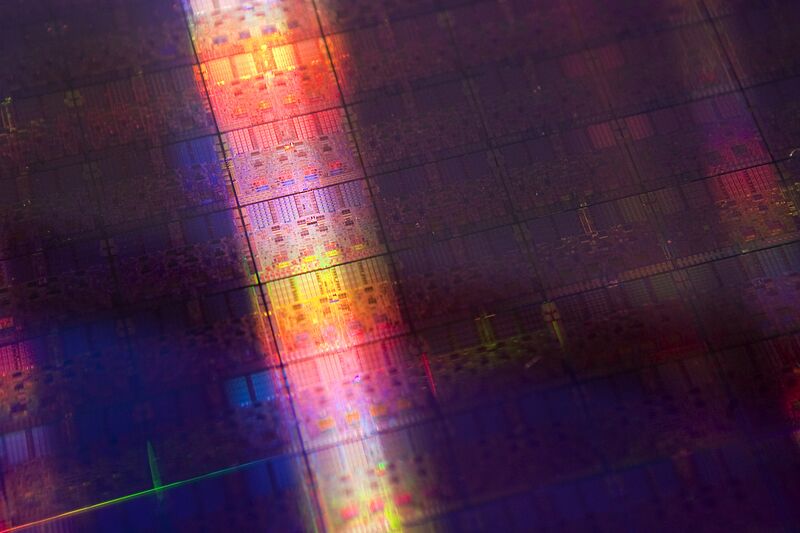

Jack Ma says he's ready for China to make semiconductors at home. It's a longstanding goal for the Chinese government. And thanks to a recent crackdown on certain technology exports by the U.S., it's now a critical one. The question is whether China can finally conquer this challenge after decades of failures. Semiconductors are the building blocks of electronics, found in everything from flip phones to the servers that make up a supercomputer. Although China long ago mastered the art of making products with semiconductors produced elsewhere (the iPhone is the most famous example), it wants to move beyond being a mere assembler. It aspires to being an originator of products and ideas, especially in cutting-edge industries such as autonomous cars. For that, it needs its own semiconductors.

Jack Ma says he's ready for China to make semiconductors at home. It's a longstanding goal for the Chinese government. And thanks to a recent crackdown on certain technology exports by the U.S., it's now a critical one. The question is whether China can finally conquer this challenge after decades of failures. Semiconductors are the building blocks of electronics, found in everything from flip phones to the servers that make up a supercomputer. Although China long ago mastered the art of making products with semiconductors produced elsewhere (the iPhone is the most famous example), it wants to move beyond being a mere assembler. It aspires to being an originator of products and ideas, especially in cutting-edge industries such as autonomous cars. For that, it needs its own semiconductors.

That's no small challenge. China is currently the world's biggest chip market, but it manufactures only 16 percent of the semiconductors it uses domestically. It imports about $200 billion worth annually -- a value exceeding its oil imports. To cultivate a domestic industry, the government has slashed taxes for chip makers and plans to invest as much as $32 billion to become a world leader in design and manufacturing. Yet as history shows, spending won't be enough.

China's earliest semiconductor was built in 1956, not long after the technology was invented in the U.S. But thanks to the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, whatever momentum its engineers and scientists had was soon lost. When the country reopened for business in the 1970s, officials quickly realized that semiconductors would be a key part of any future market-based economy.

Almost from the start, though, central planning proved to be a serious impediment. Early government ideas included importing secondhand Japanese semiconductor lines that were outdated before they were even shipped. Expensive efforts to build a domestic industry from scratch in the 1990s faltered due to bureaucracy, delays and a lack of customers for the kind of chips China was making.

Another weakness was a lack of capital. For decades, labor-intensive industries -- such as assembling mobile phones -- were the route to riches in China, attracting investment from entrepreneurs and bureaucrats alike. Making semiconductors, by contrast, requires billions in up-front capital and can take a decade or more to see a return. In 2016, Intel Corp. alone spent $12.7 billion on R&D. Few if any Chinese companies have that capacity or the experience to make such an investment rationally. And central planners typically resist that kind of risky and far-sighted spending.

China seems to recognize this problem. Since 2000, it has shifted away from subsidizing semiconductor research and production, and toward making equity investments, in the hope that market forces could play a larger role. Yet funds continue to be misallocated: Over the past 18 months, there's been a spate of government-juiced overinvestment in semiconductor plants, many of which lack sufficient technology. Those that eventually open will likely contribute to a glut in memory chips, spelling financial trouble for the domestic industry.

But perhaps the biggest long-term challenge for China is technology acquisition. Though the government would like to develop an industry from the ground up, its best efforts are still one or two generations behind the U.S. A logical solution would be to buy technology from American companies or form partnerships with them. That's the route taken by cutting-edge firms in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

Yet China can't do the same. Its efforts to purchase American semiconductor companies (often at huge premiums) are regularly blocked for security reasons. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have put Chinese acquisitions under similar scrutiny. By one accounting, China has made $34 billion in bids for U.S. semiconductor companies alone since 2015, yet completed only $4.4 billion in deals globally in that span.

Despite these impediments, China has actually made substantial strides in recent years. Companies such as Shanghai-based Spreadtrum Communications Inc. are designing semiconductors for mobile phones and other technologies, then outsourcing production to foreign plants. Meanwhile, China's considerable investment in factories that make older technologies has provided managers, engineers and scientists some crucial lessons in how to run a semiconductor fabrication business.

None of these efforts will provide the shortcuts that government officials -- and Jack Ma -- seem to want. But they might offer the building blocks for an industry that China has spent half a century trying and failing to create.

No comments:

Post a Comment