By COLIN CLARK

HONOLULU: As Seoul residents awaken to the whoomp, whoomp of the first North Korean shells and air raid sirens wail, millions pour from their apartments to the street, desperate for the shelter of the city’s 1,500 miles of deep tunnels. Some stream to the city’s rivers, hoping to head south. North Korean special operations troops, of course, have already mined some of the tunnels to help create havoc. Others have earlier swept into the tunnels to prepare ambushes and establish communications throughout the city.

HONOLULU: As Seoul residents awaken to the whoomp, whoomp of the first North Korean shells and air raid sirens wail, millions pour from their apartments to the street, desperate for the shelter of the city’s 1,500 miles of deep tunnels. Some stream to the city’s rivers, hoping to head south. North Korean special operations troops, of course, have already mined some of the tunnels to help create havoc. Others have earlier swept into the tunnels to prepare ambushes and establish communications throughout the city.

South Korean and American troops, relatively untrained in tunnel warfare and stripped of their usual advantages of communications, navigation and sensors due to the depth and length of the tunnels, are hamstrung as well by the huge numbers of civilians, whom the North Koreans are all too happy to shoot through when needed.

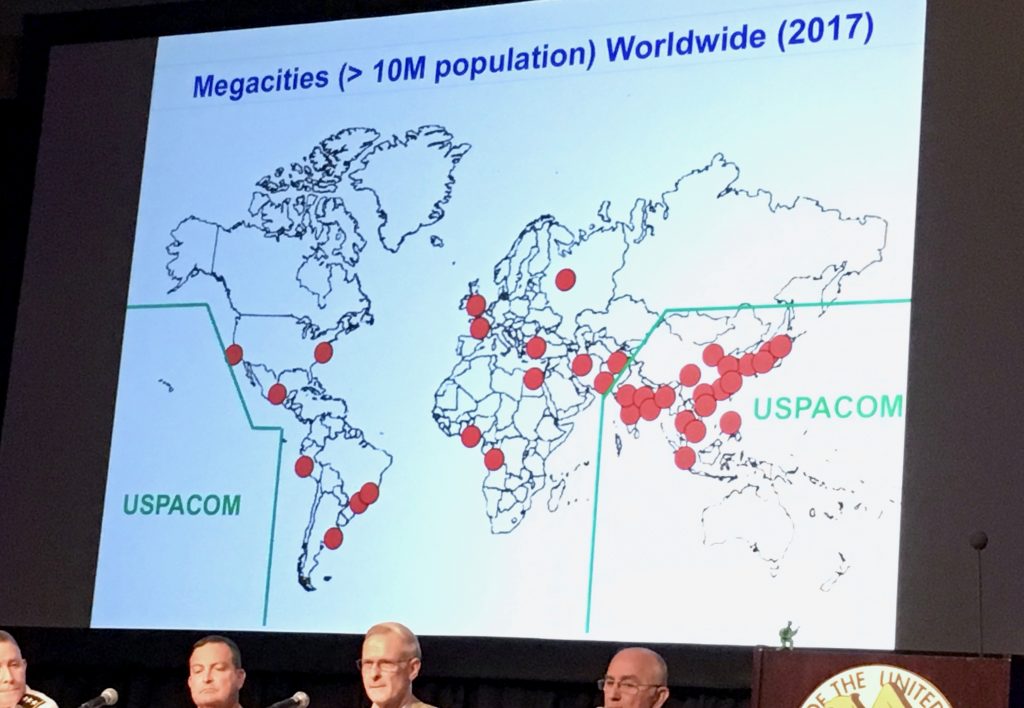

Those are just some of the challenges the US and its allies could face should war come with North Korea or China in one of Asia’s gigantic megacities like Seoul. Currently, there are no large-scale tunnel training facilities in the US and most urban training facilities are fairly small, designed to improve troops’ tactical skill, not give them and their commanders lessons in how to navigate, communicate, command and fight in a megacity.

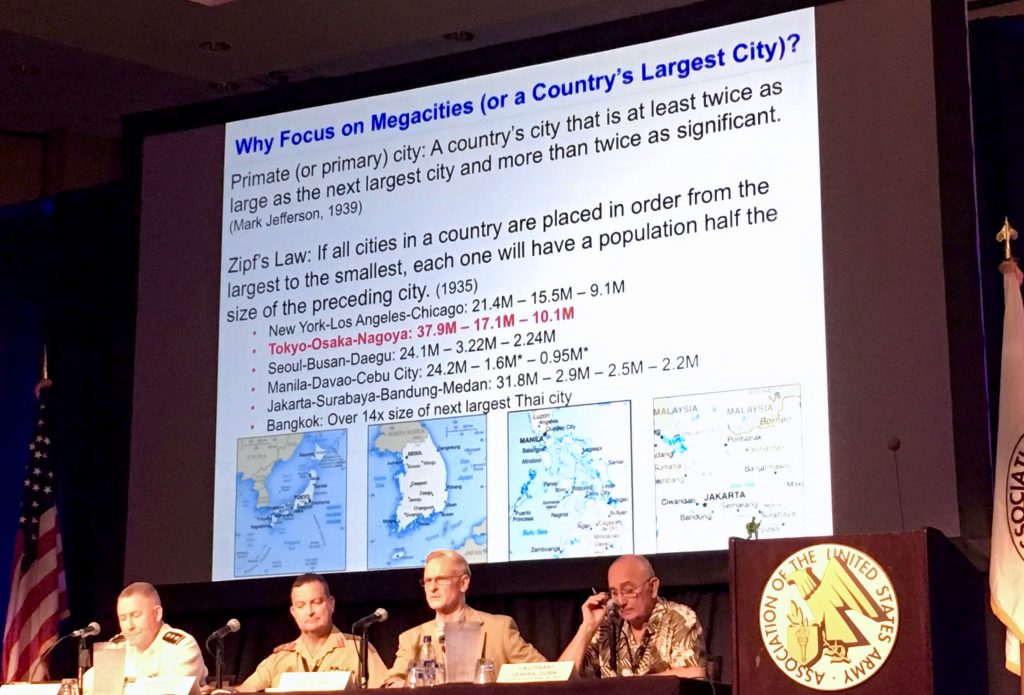

But the larger problem of how to fight and win in and around the world’s megacities is a fundamental challenge to US forces, whose doctrine has long been to surround, isolate and avoid large cities, Lt. Gen. Michael Bills, Joint Forces Korea Chief of Staff, told AUSA’s LANPAC conference Wednesday. It’s a crucial challenge for multi-domain operations because information, cyber and electronic warfare will be central to managing the fight.

(NOTE- The Army no longer refers to multi-domain battle, Gen. Stephen J. Townsend, head of Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), told the LANPAC conference on Tuesday, The new term is “more inclusive,” he said. Other speakers noted battle implies kinetics, death and destruction, while multi-domain operations may or may not result in kinetics.)

For scale, consider the Battle of Stalingrad, viewed by many military historians as the grimmest urban battle in history. While about 2 million troops battled for the city for five months, Stalingrad itself only had a population of 450,000 before the fighting started. But the casualties were astounding: 1.12 million Soviet soldiers and 768,000 German and allied troops.

The Battle of Mosul, which some have (I think incorrectly) compared to Stalingrad, lasted nine months and involved less than 150,000 troops and resulted in roughly 15,000 casualties. And Mosul had a much, much larger population of about 1.5 million before the fighting started and after ISIS had taken control.

US and allied troops faced serious difficulties in prosecuting the battle against ISIS in Mosul. Deep tunnels protected ISIS fighters. Rubble reduced the effectiveness of American munitions in many cases, helping to disperse the force of weapons. The relentless pressure not to harm civilians drove actions that may have slowed progress.

But above all else neither Mosul nor Stalingrad exhibited anything close to the scale of a modern megacity such as Jakarta, a Seoul, a Tokyo, a Guangzhou or a Beijing.

“First of all, the challenge of megacities is unlike what we have had to deal with in the past,” said Russell Glenn, director of plans and policy for the G-2 at Army Training and Doctrine Command. Aside from enormous populations, incredible population densities and enormous size, they possess an incredibly wide range of infrastructure and incredibly varied social and cultural facets. They are also absolutely central to their countries’ economies, Glenn noted. For example, the GDP of the conurbation of Tokyo is greater than all of Spain’s, and is about same as Texas. Destroy that city and you destroy much of the Japanese economy.

From a strictly military point of view, it’s much more difficult to contain the effects of destruction and death wielded in a megacity, Townsend told AUSA’s LANPAC conference: “When you are out in a rural area or small village, you can probably contain or isolate the effect of your operations, including the things that you say, the things that you do, the destruction that you create, the casualties you inflict.”

Several speakers at the conference, including Gen. Bills, noted that while recent tech improvements, such as small hockey puck-sized communications repeaters for use in tunnels, are helpful, they face serious constraints posed by the cities’ size, the depth of their tunnels and their construction of reinforced concrete and other materials.

Also, destroying key cultural sites in a megacity can have enormous and difficult to foresee consequences not only in the city but throughout the country. One speaker compared military actions in a megacity to throwing a pebble in a pond — they keep rippling outwards.

Information and cyber operations will become much more important in such circumstances, as will training in languages and cultures to anticipate and manage responses.

If one thing became clear from the several panels at LANPAC that discussed megacities, it is that the scale of command and control, the need to preserve the city and its inhabitants as much as possible while still prosecuting combat operations are issues the US Army, and the US military in general, are just beginning to grapple with.

No comments:

Post a Comment