CAPITOL HILL: In war, no weapon or technology matters as much as leadership. That’s why the Senate Armed Services Committee wants to modernize the military’s rigid Cold War processes for promoting officers. The goal: turn today’s one-size-fits-all system into something flexible enough to cultivate the many different types of talent required for modern conflict, from hackers to pilots to grunts. The House, however, is holding back: HASC’s version of the annual defense policy bill contains fewer and less radical reforms.

CAPITOL HILL: In war, no weapon or technology matters as much as leadership. That’s why the Senate Armed Services Committee wants to modernize the military’s rigid Cold War processes for promoting officers. The goal: turn today’s one-size-fits-all system into something flexible enough to cultivate the many different types of talent required for modern conflict, from hackers to pilots to grunts. The House, however, is holding back: HASC’s version of the annual defense policy bill contains fewer and less radical reforms.

“That’ll be the uphill battle, getting this through conference,” a SASC staffer told me yesterday, on the eve of the committee releasing its draft of the National Defense Authorization Act for 2019. “I told DoD (the Department of Defense), if you don’t like what’s in our mark, you know your strategy: Go talk to HASC.”

Now, House Armed Services chairman Mac Thornberry isn’t adverse to reform in general. This year, for example, he has proposed dramatic cuts to the Pentagon’s “fourth estate” of support agencies — proposals that the Senate’s not yet adopted, setting up another clash in conference.

But the fourth estate is largely staffed by civilians, and Thornberry has been more deferential to the Defense Department about military personnel. Senate chairman McCain, by contrast, is a former military officer and war hero himself. He knows the dysfunctions of the system first-hand, and deference to DoD — or anyone, for that matter — is just not his style.

The House bill does contain provisions on officer management, but they’re all things the Pentagon itself requested, the SASC staffer said. For larger reforms, HASC seems willing to wait for the recommendations of a congressionally mandated study the Defense Department will submit December. SASC isn’t waiting, because it has no confidence DoD’s report — prepared by the thinktank RAND using traditional retention models — will call for real change.

West Point cadets conduct a cyber exercise.

Options, Not Mandates

The Senate bill mainly creates options the armed services can use or ignore at their discretion. In most cases, it doesn’t outright require the services abandon the current system, enshrined in law by the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act of 1980.

“Most of this is permissive stuff,” the SASC staffer said. “If you like your DOPMA, you can keep your DOPMA….. We’d like the services to take advantage of these things, and we’ll try to encourage them to do so, but there are very few mandates or requirements.”

Because the reform is mostly optional, “the services are supportive of some of the (reforms) on an unofficial level,” the staffer said. “It wasn’t seen as a controversial thing once they actually saw the bill text.”

So what are the principal provisions? Hang on, because this gets technical:

Flexible promotion timelines

Today, officers come up for promotion at predetermined points in their career. If the promotion board decides you’re not qualified at that point, it’s very hard to get another chance. As a result, officers have to follow a fairly standardized career path to get all the right job experiences in time — command this kind of unit, work on that staff, go to this training — with little leeway for out-of-the-box experiences like graduate school or advising foreign forces. The timeline’s so tight that you can’t typically spend more than two or three years in the required assignments if you want to fit them all in, which means constant turnover in unit leadership.

A promotion board for non-commissioned officers (NCOs)

Now, the system’s not completely lockstep. It’s possible for promising officers to be promoted early, “below the zone,” or for late bloomers get a second chance “above the zone” after being passed over once. But for most people, if you’re not promoted on schedule, “in the zone,” you’re not getting promoted at all. And those who are “below the zone” are often targeted for promotion before, many say, they demonstrate the strategic understanding crucial to becoming a three or four star general.

The Senate bill would allow — not require — the service secretaries to exempt certain categories of officer from the normal timeline requirements, giving them up to five additional chances at promotion to a particular rank. For example, young cyber officers could be given additional time to qualify for the rank of major, allowing them to go to grad school in computer science or take fellowships with cutting-edge private sector companies. Foreign area specialists could get more time to live abroad as embassy attachés, military advisors, or students. Pilots could get more time in the cockpit instead of at a desk.

Competitive Categories

Another provision encourages the services to create more officer categories. Each service has broad discretion over how many so-called competitive categories to recognize. The Navy divides its officers into 20 groups, for example, each with its own promotion track, so that (for example) a submariner, a hacker, a lawyer and a doctor aren’t all competing with each other. Other services have fewer categories, so an Air Force pilot might be competing against, say, a finance officer. That can be problem because service cultures generally promote warriors over technical specialists, no matter how necessary the techies might be for modern war. That is especially true in the largest service, the Army, which is notorious for not promoting officers to the top ranks unless they come from one of the combat specialties. The Senate bill requires service secretaries to “consider qualifications, specializations, and occupation” in creating new categories, in the hope the services will create more fine-grained ones that give vital specialists better chances at promotion.

No Year Groups

Conversely, the SASC bill would ban managing officers by “year group,” a system currently used by the Army and Air Force, but not the Navy and Marines. In a year-group system, everyone commissioned as an officer in a given year goes up for promotion to a given rank at the exact same time. If your year group is unusually small — because of problems with recruiting and retention, or because the service had budget cuts and got rid of people — then your chances of promotion will be better for the rest of your career. If your year group is unusually large, your chances of promotion will be worse, no matter how good you are as an individual. And, of course, if your year is both large and filled with especially talented folks, your chances get even slimmer. SASC would ban this practice, forcing the Army and Air Force to compare officers who entered in different years.

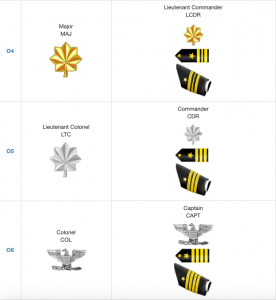

Field grade officer ranks and insignia: Left column is Army, Air Force, & Marines; right column is Navy and Coast Guard

Stricter Continuation Criteria

If you don’t get promoted on time, the military traditionally operated on an “up or out” system: People passed over for promotion typically had to leave the service by a set time. Today, the services give waivers so routinely — a process called “selective continuation” — that the “…or out” aspect of the system is effectively dead, the Senate staffer said. The SASC bill would give the system some teeth by allowing passed-over officers to stay only if they can get a specific unit to say it wants them to fill a specific job. Can’t get promoted and can’t convince anyone to (in essence) hire you? You’re gone.

Field-Grade Flexibility

Today, DOPMA specifies, by law, how many mid-ranked “field grade” officers each service is allowed to have, with a sliding scale based on the total number of troops in uniform. (Field grades are paygrades O-4, O-5, and O-6: That’s majors, lieutenant colonels, and colonels, or, in the Navy, lieutenant commanders, commanders, and captains). But the DOPMA formula is based on industrial age warfare. Modern conflict requires more technical specialists and foreign area advisors, whose experience and training tends to put them in the middle ranks. So SASC would abolish the tables and instead require the services to request and justify how many field grade officers they need year by year. The number of generals and admirals would remain strictly capped by law.

The SASC bill would also expand temporary “spot promotions” to field grade rank, remove certain maximum age restrictions on officers, and allow experienced civilians — say, cybersecurity experts — to enter at higher ranks. SASC and HASC both include a Pentagon proposal to let officers postpone when they go before a promotion board, allowing them more time to take non-standard assignments and still get all the experiences required for the next rank.

The SASC bill would also expand temporary “spot promotions” to field grade rank, remove certain maximum age restrictions on officers, and allow experienced civilians — say, cybersecurity experts — to enter at higher ranks. SASC and HASC both include a Pentagon proposal to let officers postpone when they go before a promotion board, allowing them more time to take non-standard assignments and still get all the experiences required for the next rank.

The current system has its roots in World War II, when Gen. George Marshall relieved and replaced 31 of 42 senior officers after the famous Louisiana Maneuvers. Marshall acted because the Army was then run by scores of superannuated generals promoted under a pre-war system of strict seniority. DOPMA was designed to train up large numbers of young, fit, but interchangeable officers to command a mass mobilization against the Soviets. Today’s conflicts require a very different force, as described in the recent National Defense Strategy.

“The NDS lays out fundamentally different priorities, chiefly adaptability and flexibility,” the staffer said. “When you think of DOPMA, adaptability and flexibility are not two words that go along with that..”

No comments:

Post a Comment