By Tim Prior

According to Tim Prior, the ‘fifth wave’ of deterrence development is rising at a point when established approaches are fumbling to provide an effective response to complex contemporary security threats. However, Prior believes that an answer lies in resilience thinking. Indeed, he argues that resilience can increase the ability of security institutions to cope with complex threats, for instance, by reducing vulnerabilities and denying threatening actors suitable targets for their attacks. This article was originally published in Strategic Trends 2018 by the Center for Security Studies on 13 April 2018.

According to Tim Prior, the ‘fifth wave’ of deterrence development is rising at a point when established approaches are fumbling to provide an effective response to complex contemporary security threats. However, Prior believes that an answer lies in resilience thinking. Indeed, he argues that resilience can increase the ability of security institutions to cope with complex threats, for instance, by reducing vulnerabilities and denying threatening actors suitable targets for their attacks. This article was originally published in Strategic Trends 2018 by the Center for Security Studies on 13 April 2018.

The concept of resilience is becoming more relevant for current deterrence debates at a time of evolving threats. The fifth wave of deterrence development is rising at a point when established international security practices are fumbling to respond effectively to security challenges. Resilience can increase the ability of security institutions to cope with and respond to complex threats in a deliberative manner. Security policy decision-making processes must match the complex threat environment they seek to govern by being flexible, proactive, and distributed.

Deterrence is relevant again. Twenty-eight years after the end of the Cold War, and four years after the annexation of Crimea, NATO and its member states have to re-learn many lessons that previous generations knew by heart. However, nothing could be more dangerous than just re-applying old recipes to new challenges. As the threat evolves, so must the answer to deter those who threaten.

An important part of any answer has to be resilience. The concept has swept across multiple and diverse policy spaces since the turn of the 21st century. It is neither a “silver bullet” nor a buzzword that will fade with a new publication cycle of the think tank bubble. Resilience offers a unique paradigm for managing “predictable unpredictability”.1

Jordanian soldiers take part in “Eager Lion”, a multi-national military exercise focusing on facing irregular warfare, terrorism and national security threats. Muhammad Hamed / Reuters

What, then, is resilience? For example, we know that, unfortunately, terrorists will strike again in 2018. In an ideal world, using previous experience, with appropriate planning, and with the ability to adapt the way we proactively deal with the possibility of such horror, the impact, or even the occurrence, of a terrorist strike where we last expect can be minimized. In the context of security, this is what resilience means: that we establish socio-technical systems with the dynamic ability to anticipate and respond proactively to potential threats by learning and adapting.

This chapter reflects on the rise of resilience in security policy over at least the last ten years. It focuses in particular on the more recent trend towards the view that the successful product of over a decade of resilience thinking and action, is the benefit it offers policy-makers. Resilience, argues this chapter, can bolster deterrence. Of course, as the new denial kid on the block, resilience will not supersede other approaches (especially deterrence by punishment), but this chapter explores ways that resilience might complement existing deterrence tactics.

Naturally, any deterrence debate in Europe focuses first and foremost on NATO and its deteriorated relationship with Russia. Indeed, it is NATO that is primarily responsible for defending its member states and deterring existential threats – both as a nuclear alliance and as the still most effective framework for collective military action. And the alliance faces new challenges: As Russia appears to be leaning towards a broader and deeper understanding of deterrence in the form of “cross-domain coercion”, emphasizing non-military means, subversion, and information warfare besides an aggressive and ambiguous communication of its nuclear might, NATO has to adapt. In the mix of necessary answers, resilience will play an important role.

NATO has stated that it is committed to finding this mixture:2 “We […] stand united in our resolve to maintain and further develop our individual and collective capacity to resist any form of armed attack. In this context, we are today making a commitment to continue to enhance our resilience against the full spectrum of threats, including hybrid threats, from any direction.”

Still, while NATO will retain primacy in the deterrence realm, other actors will face similar challenges. In its Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy, the EU is explicit:3 “The EU will foster the resilience of its democracies. Consistently living up to our values will determine our external credibility and influence.”

And that: “It is in the interests of our citizens to invest in the resilience of states and societies to the east stretching into Central Asia, and to the south down to Central Africa.”

Even “hard security allies” like the US and the UK have embraced resilience as part of their agenda. As laid down in the US National Security Strategy:4 “We must build a culture of preparedness and resilience across our governmental functions, critical infrastructure, and economic and political systems.”

Noting that: “A stronger and more resilient critical infrastructure will strengthen deterrence by creating doubt in our adversaries that they can achieve their objectives.”

The UK’s National Security Strategy offers similar wording: “We will strengthen our domestic resilience and law enforcement capabilities against global challenges which increasingly affect our people, communities and businesses.” 5

While some commentators argue that this strategic, and aspirational, language is too vague to be useful,6 in fact resilience is a practical tool in a complex risk and threat landscape where preventing threat is less successful than establishing coping mechanisms. This chapter examines where resilience has arisen within deterrence discussions, and explores how the process of building resilience is relevant and useful in the context of credible threat deterrence. Often, strategic aspirations are just that: aspirations. But there are excellent reasons to think about deterrence from a resilience perspective – like embracing complexity and transformation in uncertain contexts – and the chapter explores these.

The chapter highlights where opportunities must be taken to embrace new approaches to managing security in complex security systems. In this respect, it explores the practicality of resilience in the current deterrence discussion, but at the same time acknowledges that resilience is a new element that will complement existing approaches.

Modern Challenges in Deterrence

Sun Tzu told us the most artful skill in war was subduing the foe without resorting to fighting. Deterrence, whether by denial or punishment, is premised on the notion that an actor can disrupt an adversary’s strategy. In essence, deterrence is thus a psychological means of altering the cost-benefit interaction between actor and adversary that is influenced by assumptions about power, and the ability to meet the goals of one’s strategy.7 To understand why and how resilience can bolster deterrence, it is helpful to examine how deterrence theory evolved - and where we stand now.

An actor’s deterrence strategy must be seen as credible by an adversary. In order to be credible, the deterring actor must communicate both capability and commitment. In the dyadic deterrence situation during the Cold War, achieving these criteria was complicated, but manageable. This was because the deterrence relationship between the USSR and NATO at the time was essentially based on a shared normative framework. Presumably, the classical deterrence formula of “assured destruction” worked because it was clearly understood by both sides.

Today, deterrence has become more complex. There are more actors, including non-states actors, underscoring the need for the communication aspect of deterrence to be strengthened. Exactly because of the increasingly complex deterrence atmosphere, there is a risk of failure when an actor does not understand their adversary.8 The inability to understand the adversary might be associated with cultural, religious, political, or historical differences between actor and adversary. It may also occur if the actor does not keep abreast of the adversary’s developments in capability or approach. In any event, many believe that the likelihood of deterrence failure has increased.

Deterrence, in theory and practice, has evolved in four waves9 – from the end of the Second World War until after the collapse of the USSR. Importantly, the concept and practice of deterrence has been closely linked to the development of nuclear weapons and the threat of nuclear war.

Prior to the introduction of nuclear weapons into conflict, the application of deterrence in policy was limited – war was assumed, and the key strategy was to win. With nuclear weapons available to states, international security relations shifted towards the imperative of deterring conflict because the potential consequences of a nuclear war would be too great. During this second wave, deterrence was mainly a matter between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, based on the assumption of “assured destruction”, which would dissuade conflict on the basis of punishment. Slowly, deterrence by punishment began to be differentiated from deterrence by denial. Where punishment was seen to add costs into the deterrence relationship, denial was focused on preventing an adversary’s goals from being met, thereby removing benefits.

During the third wave of the development of deterrence, leading up to the breakup of the USSR, practical evidence demonstrated the importance of the goals at stake in influencing the success of deterrence. This was especially due to the disruption brought by new technologies and non-state actors that have increasingly complicated the actor-adversary relationship. The cost-benefit nature of classical deterrence was also disturbed by the inclusion of incentives into the deterrent formula.

The idea of “tailor-made deterrence” established the need for the application of flexible and adaptive deterrence strategies, especially because of the recognition that deterrence could fail. This also helped to shift the focus of deterrence from punishment to denial.

The fourth wave has been underway since the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the USSR. It has been characterized by asymmetric threats, unclear actor relationships, and the activities of states whose actions were perceived as irrational, among other complications. These changes in the international security policy sphere have led to an increasingly unpredictable and uncertain strategic operating environment.

For example, the effectiveness of modern US deterrence strategy has been frustrated by the actions of adversaries who have exploited technological advancements and the spread of cheap but accurate weapons, and the use of cyber tools.10 More concretely, Russia’s ability to hack the electronic voting systems of the US in 201611 suggests US security policy, action, and the identification of the adversary’s goals, lagged behind Russian intent and capability. Merely thinking a system is secure is not an assurance of security, or the basis of a deterrent posture; nor is a system invulnerable to attack by an adversary if its inherent vulnerabilities are unknown to the actor. Implementing resilience can be a means of addressing these issues.

As a form of denial, resilience is useful in complex interactions where actors are unfamiliar with each other’s strategies. Complexity complicates familiarity – with actors and with situations. When applying deterrence approaches under these conditions, it can appear that adversaries are beyond deterrence because they simply don’t respond in an expected manner.12 However, the goal-oriented nature of emergent terrorist, hybrid, and cyber-threats,13 for example, can be more effectively dealt with using deterrence by denial. Because the goal focus in these contexts is so strong, the inability to achieve these goals has negative higher order consequences with respect to the success of an adversary’s cause.14

The Rise of Resilience in a Diverse Threat Environment.

The word “resilience” is derived from the Latin resilire, meaning to spring or bounce back. At the most basic level, resilience implies the ability of an entity or system to return to normal functioning or a normal state quickly following a disturbance: an entity “bounces back”. Since its early application (in the context of engineering resilience, for instance), a more nuanced conception of resilience, beyond the ideas of stasis or a single equilibrium, has found traction. Here, flexibility and change are considered to contribute to a positive process of learning and adaptation. Resilience is not necessarily about “robustness”, but about transformation. Transformation and flexibility are system characteristics that permit a system to persist under challenging conditions with the same components and much the same (or better) function.

The pervasiveness of resilience in the context of national and international crisis and security policy is evidenced by the growing number of states having identified the resilience of technical and social systems as a goal in their security strategies. The desire to become resilient is, on the one hand, likely a popular response, but on the other, also reflects national and international insights and experiences that suggest complete security is impossible to guarantee, and that threat prevention is imperfect.

“Resilience thinking” must be differentiated from “being resilient”. Resilience thinking involves decision processes that involve anticipation, adaptation, being flexible, and focusing on the inclusivity of diverse decision-makers.15 Resilience thinking is neither hierarchical nor deterministic, but rather networked and distributed. Resilience thinking is useful in the context of complex systems, where interactions within relationships yield uncertain and unpredictable consequences, and where linear decision processes are sub-optimal. Being resilient can be thought of as the outcome of resilience thinking. Resilience thinking should influence the ability of populations, structures, organizations, and institutions to withstand, or recover quickly from disturbances. Entities that are resilient are typically less vulnerable to disturbance, and the ability to demonstrate reduced vulnerability is the key element that being resilient lends to discussions about threat deterrence.

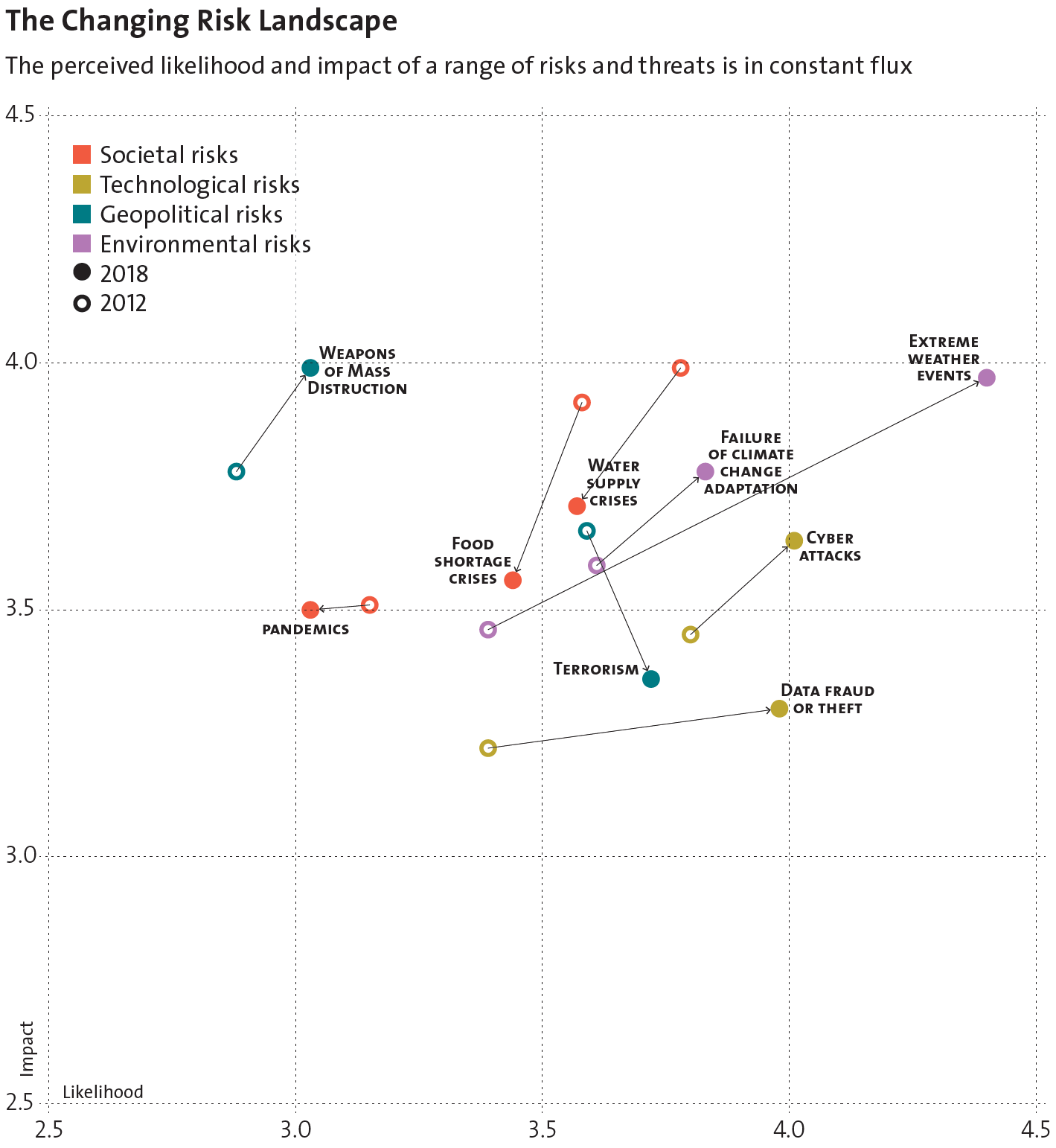

Sources: World Economic Forum (2012 and 2018), Global Risks 2012 Seventh Edition and The Global Risks Report 2018 13th Edition

Resilience thinking accepts that even the best planning and organization cannot prevent security breaches. Resilience thinking acknowledges the inherent difficulty of attempting to identify and address all vulnerabilities and threats, and that actions and responses create positive and negative feedback loops that influence the transformation and evolution of problems and solutions. Resilience thinking actively links adaptation and learning to the ability to anticipate threats, thereby creating a basis on which to mitigate the consequences of ‘predictably unpredictable’ threats.

Finding a catch-all resilience thinking approach is next to impossible,16 which is important in the context of security, because no two threat situations can be dealt with in the same way. In part, this is where more traditional risk management approaches have proven insufficient. Risk management portrays an illusion of top-down controllability, being a hierarchical and deterministic means of stepping through a systematic process of risk identification, assessment, prevention or control, and review. Risk management is a good way of dealing with complicated problems in a top-down manner. Unfortunately, it’s not so easy to corral the 21st century threat landscape into this formulaic process. Resilience thinking lends itself more appropriately to dealing with complex problems in a bottom-up, or non-hierarchical manner.

One commonality of national and supra-national resilience policies is that they point to the importance of lower-scale actors and actions in contributing to resilience, making clear that citizens, communities, organizations, and institutions all share responsibility for national security. Several factors have driven this shared assumption, including recurring experiences with security threats, limited or insufficient higher-level responses, difficulty predicting and preventing security threats, critical infrastructure privatization, and the simple desire of the public to be more engaged in decisions that affect them. Resilience thinking has become the model of choice for a more distributed approach to security, where self-organization of actors is seen as the foundation of more sustainable and diffuse responses to identifying and addressing diverse threats. This is important because contemporary threats are themselves distributed and networked.

Complexity and Resilience

“Deterrence today is significantly more complex to achieve than during the Cold War.”17

In a diverse and complex threat environment, guaranteeing security is difficult. The statement above, from the US National Security Strategy, couches this problematic as a future strategic challenge. In practice, most national governments retain a traditional preventative and territorial approach to security18 that is less suited to this new threat environment characterized by complexity, transformation, and “massive uncertainty.”19 Meeting the challenges of an uncertain and unpredictable future, characterized by novel and asymmetric threats, requires a phase shift in policymaking: “When war changes, so must defense.”20

To understand why a resilience approach presents advantages in future deterrence, it’s necessary to discuss what complexity means, and to think about deterrence and international security as two interacting systems.

In describing the modern threat environment, we must distinguish between complex and complicated systems. A complicated system has many parts, which interact in a well-defined and predictable manner. By contrast, a complex system is organized not as a hierarchy, but as a series of interconnected sub-systems whose relationships are unpredictable, and where these unpredictable relationships can influence the way the broader system changes. Whereas changes in a complicated system are predictable, changes in a complex system are non-linear and emergent.

Two examples can illustrate the differences. An aircraft is a good example of a complicated system. While there are many interdependent parts in the aircraft, the pilot controls the plane with known and predictable operations. If something goes wrong, a checklist is often enough to narrow down the source of the issue.

The ongoing campaign to subdue international terrorist organizations is an example of a complex system. Again, there are many elements in the system, but exerting pressure on one element has unpredictable implications or feedbacks for other elements, and the system as a whole. Arguably, the US response to the 9/11 attacks, and the threat from al-Qaida in Afghanistan, was conducted in a traditional way, hoping military might would subdue the threat. To the chagrin of several commanders, the complexity of the situation illustrated how important a detailed understanding of the various interactions between adversaries, with the geography, local civil populations, technologies, etc., could be for achieving a positive outcome in the complex security situation.

International security, to the extent that it involves deterrence, can also be thought of as a complex adaptive system. The nature of the relationships between the sub-systems that make up the international security system bestow a capacity for proactive and reactive adaptive learning. In actual fact, complex adaptive systems do not change through learning, but emerge from the interactions with other connected complex adaptive systems – if the US military acts one way, al-Qaida quickly reacts. Based on these interactions, the system evolves. Under such circumstances, reductionist approaches, like traditional hierarchical risk management, represent sub-optimal coping tools.

The nature of deterrence is facing a phase shift, driven by the multifaceted and complex nature of the modern threat landscape. Realistically, deterrence must be a flexible and proactive occupation, composed of elements that should suit the nature of the threat. The notion of “tailor-made” deterrence begins to address the complexity of modern threat by attempting to introduce a more detailed understanding of the complex threat situation in order to direct a customized response.21

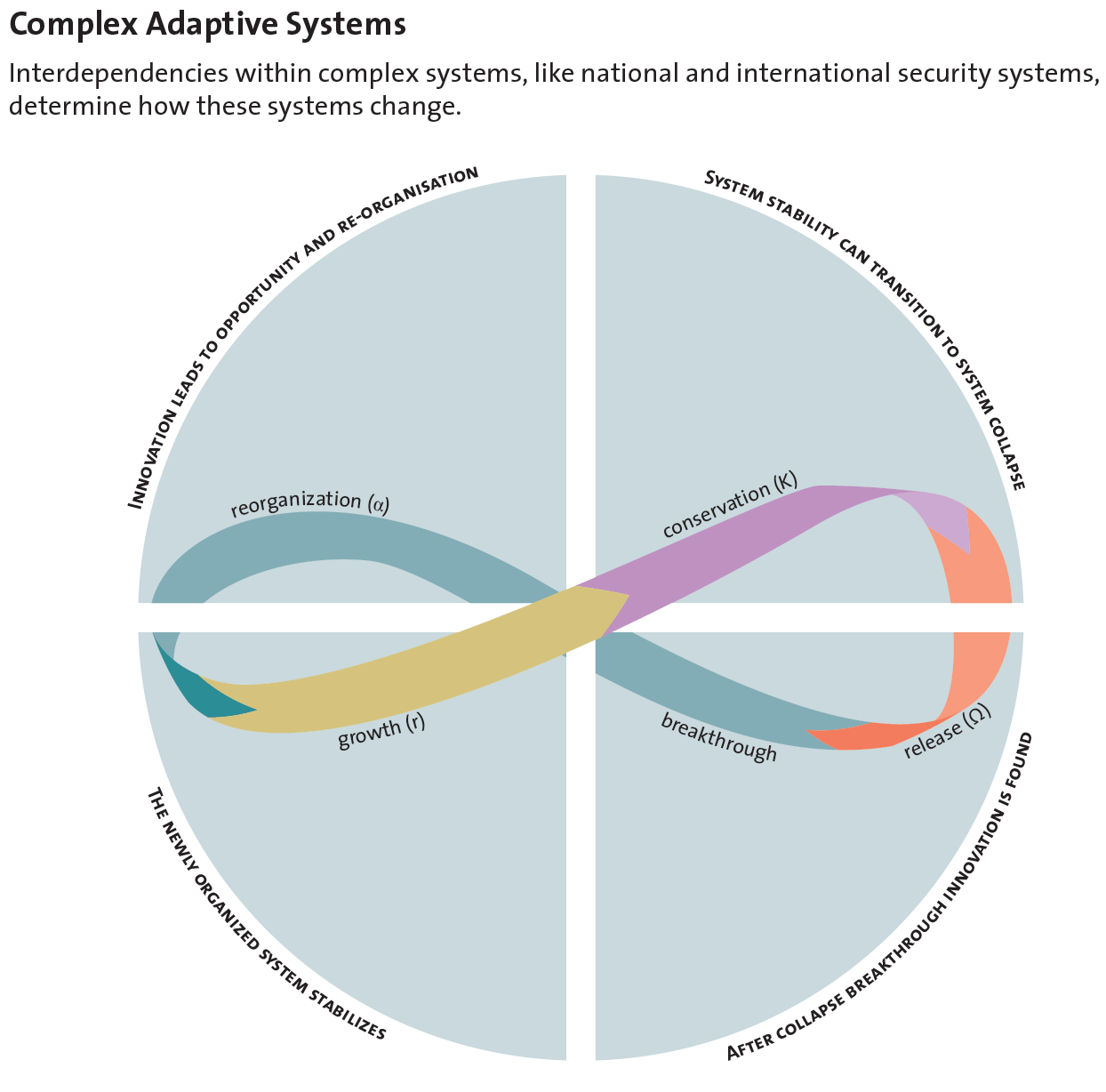

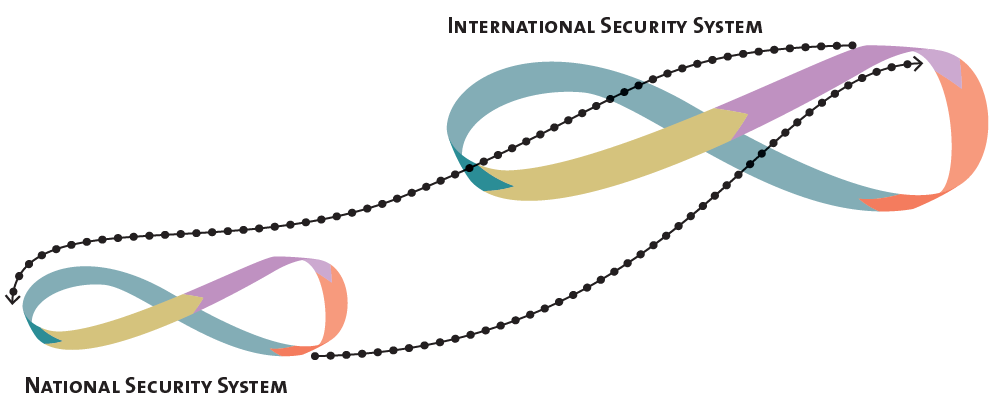

Resilience thinking can be a powerful means of guiding the development of an adaptive tailor-made deterrence approach. The national-international security landscape is illustrated as two interacting “Complex Adaptive Systems” on page 73. The international and national systems interact and respond to one another as they develop and change.22 Within this system, information and control is multi-directional, flowing between the systems – a state of affairs that has been described as “panarchy”.23 This is in contrast to a typical hierarchical system, where control is exerted in a unidirectional manner. Complex human, socio-technical, and human-ecological systems are arranged as panarchies – as systems that feature nested components, open information flow, and constant change. No element in these systems can be thought of as the ultimate point of control.24

Given the complex threat environment, non-hierarchical decision-making processes, like resilience thinking, are particularly suitable because they match the non-hierarchical nature of the challenge to be solved. The ability of decision-makers to embrace emergent opportunities and adapt quickly is imperative. While this ability has always been important, it is the diversity in the current threat landscape that is currently pushing the deterrence phase shift from a hierarchical and deterministic mindset to a networked, non-linear, and deliberative mindset.

An adaptive cycle, represented here, consists of four stages of stabilization (r), conservation (K), destruction ( ), and reorganization (α). Periodic phases of destruction (release) give opportunities for reorganization.

All complex systems interact with other systems on multiple scales. The national security system is hierarchically smaller in scale than the international system, and changes more quickly. Both systems are interdependent with multiple feedbacks and connections. These two interacting systems are termed a Panarchy. Sources: Concept based on Lance H. Gunderson, Crawford S. Holling, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Island Press, 2002); Image adapted from Daniel Christian Wahl, Designing Regenerative Cultures (Triarchy Press, 2016) and Daniel Christian Wahl, “The adaptive cycle as a dynamic map for resilience thinking” and “Panarchy: a scale-linking perspective of systemic transformation”, in: medium.com (15.4.2017 and 9.9.2017).

Resilience as a Credible Form of Deterrence?

The credibility of resilience as a deterrent option is closely connected to the utility of resilience thinking in the context of complex threats. Resilience is practical under these circumstances because it shifts the focus from preventing complex and diverse threats to mitigating the consequences of these threats through proactive anticipation, preparation, and adaptation. The new complexity of threats (including terrorist, hybrid, and cyber-threats) is disrupting traditional deterrence approaches.

These points speak to the utility of resilience as a deterrent option in complex threat situations. However, like any other deterrent option, resilience must be credible. Given the nature of deterrence as a psychological strategy disruptor, for resilience to be a credible option it must meet three criteria that are typical of all forms of deterrence: commitment, capability, and communication.

The trend towards committing to resilience in security policy is a strong one. Given that there has already been a reasonably long focus on resilience at national and sub-national scales in the contexts of civil protection, critical infrastructure protection, disaster risk management, public preparedness, and risk communication,25 systematically scaling up resilience as a national or international security policy priority will clearly demonstrate a real commitment to resilience in deterrence.

Capability can be established through coherent and systemic development of the practical actions that together contribute to building resilience. These might include establishing comprehensive and multi-thematic vulnerability assessments; describing resilience in multiple contexts, finding commonalities; establishing measurement tools and processes; encouraging flexibility within security organizations to improve the ability to learn, adapt, and respond; and investing in developing coherent practices across security themes and sectors.

In the EU, resilience-building in security policy has been established largely as an outward-looking activity in external action. Building up the resilience of neighbors and partners beyond the central territory is seen as a key means of protecting the core. The EU’s focus on outward resilience is predicated on the importance of addressing the fragility of neighbor states (as a root of instability and conflict) to the east and south through humanitarian and development activities. It highlights that such action can minimize potential threats to vital interests within the union. In order to demonstrate capability, the EU Global Strategy suggests that a resilient society is one that “features democracy, trust in institutions, and sustainable development.”26 This is a reasonably limited conception, and a hypothetical means of demonstrating resilience capability that presumably seeks to highlight the importance of resilience in the context of social-institutional settings.

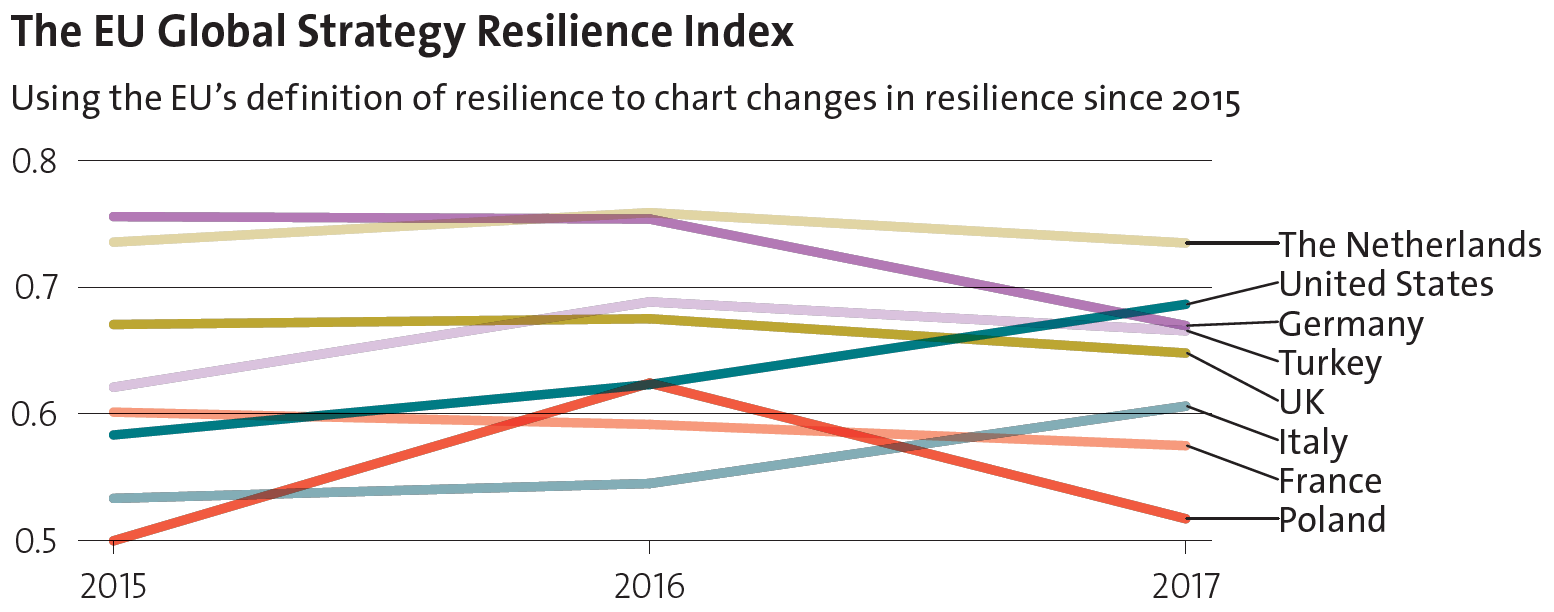

As an experiment, it’s possible to create an “EU Global Strategy Resilience Index” to track changes in the EU and beyond. Drawing on open-source data for the indicators “democracy”, “trust in government”, and “sustainable development”, a resilience score is charted on page 76. It covers the last three years across several EU, non- EU countries, and the UK and US. This basic index of national (social-institutional) resilience suggests some surprising winners and losers. Of the countries included, only the US, Japan, and Italy seem to display rising societal resilience. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the long process through which Germany has gone in forming a coalition government (from mid- 2017 to early 2018), and government delegitimization associated with the refugee “crisis” (2015), Germany’s resilience (predicated on trust in government and democratic values) has fallen dramatically. Likewise, Poland’s resilience has also shown a dramatic turn for the worse, perhaps related to the government’s attempts to undermine the rule of law in 2017,27 and the implications for democracy in that country. These (very simple) results suggest that actions to build, maintain, or demonstrate capability in societal resilience should be implemented not just in external activities in peripheral (more fragile, less stable) states, but also on the EU’s home turf. The latter is a less typical action because of a bias in the perceived external origin of threats to the EU (from the east and south), which reflects an EU-centric power asymmetry.28

Communication is the third criterion of credibility, and possibly the most difficult to achieve. Demonstrating that a critical infrastructure, or society as a whole, is resilient (or becoming resilient as a result of national measures) requires that resilience be measureable and measured. Clear communication relies on a demonstration of capability – as a resilience index could potentially do. For instance, only with concrete evidence that people or structures are becoming more resilient will the assertions of the US National Security Strategy that a “stronger and more resilient critical infrastructure […] strengthen deterrence by creating doubt in our adversaries that they can achieve their objectives”29 be borne out.

Note: The resilience index used in this figure was calculated using open-source data for the indicators “democracy”, “trust in government”, and “sustainable development”. This is a narrow conception of what might be meant by societal resilience, and the index is used merely as a tool to communicate resilience as a measured characteristic in this article. Data was unavailable for all countries, and the selection included here is therefore limited. Patterns are interpreted loosely. Sources: Jeffrey Sachs et al. (2017 and 2016): SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2017, p. 10, and SDG Index and Dashboards – Global Report, p. 37, (New York: Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network); Christian Kroll (2015): Sustainable Development Goals: Are the rich countries ready?, (Sustainable Governance Indicators, Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Bertelsmann Stiftung), p. 6; The Economist Intelligence Unit, “The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index”, in: infographics.economist.com/2018/DemocracyIndex; Andrea Silenzi (Twitter, 7.4.2017), “Confidence in #governments in many OECD countries is still lower than before the financial crisis” referring to: “Trust and public policy”, in: OECD (2017), Trust and Public Policy (Paris: OECD Publishing), p. 20, based on Gallup World Poll; OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017 (Paris, OECD Publishing), StatLink p. 215, based on Gallup World Poll; Edelman trustbarometer and Edelman, “2017 Edelman Trust Barometer” in: edelman.com/research/2017-trust-barometer-global-results, p. 12.

NATO’s push for resilience is naturally focused on member states. Problematically, though, NATO has no mandate to build national resilience directly. Nevertheless, the alliance is keenly interested in building resilience and has established a technical focus predicated on the need to build civil preparedness of critical infrastructures as a basis for the delivery of military forces and capabilities in upholding collective defense. Given the (geographic, political, technical, and social) connections between NATO members, neighbors, and partners, the desire to build resilience in the alliance will also require engagement with non-typical associates that might share borders, infrastructures, or interests.30 Whether these actions have direct or indirect implications for deterring threats on EU or NATO territory will only become evident in the future.

The very context-specificity of resilience that is one of its advantages can be interpreted as ambiguity. This can be a problem in the aspirational context of national security strategies. In commenting on discussions about cybersecurity in the US National Security Strategy, Ben Buchanan criticizes the vagary of discussions about resilience in deterrence. Rightly, he points out that “Adversaries can employ the same tactics again and again with success. And, until U.S. strategy recognizes that and stops them, they will.”31 Here lies the point: if the US, or any country with an active focus on resilience building, continues to pursue measures of vulnerability reduction, agile anticipation, resilience monitoring, assessment, evaluation, and adaptive learning in a systematic manner, then it can address these problems, and not just in the context of cyberspace, but also with respect to hybrid threats and terror.

Resilience: Guiding the ‘Fifth Wave’ of Deterrence?

“In the highly complex and dynamic international environment of the twenty-first century, policymakers […] deal with multiple actors, asymmetric relationships, and transnationally networked threats.”32

Resilience thinking and being resilient can offer concrete advantages in security policy, and specifically in deterrence. Applied resilience is becoming the cornerstone of security policy, and represents the fifth wave of deterrence.

Modern threats are complex, multi-actor, cross-scale problems, which must be met with agile, resilience thinking-style institutional decision-making that fits the nature of the problems. Proactively countering complex threats with equally networked and distributed policy responses, guided by resilience, will improve the effectiveness of those security policies. In this context, the increasing resilience of society, critical infrastructure, and organizations – the product of a decade of resilience promotion in security policies – and the concomitant reductions in vulnerability will deter asymmetric threats by denying threatening actors suitable targets for their attacks.

Where classical (nuclear) deterrence was hierarchical and deterministic, based on the known relationships between the actors, and on the simple and well-understood principle of assured destruction, which held the actors in check, modern deterrence is altogether different. Threats are uncertain, and unpredictable; actors are unknown, as are the vulnerabilities they target. As threats have become less state-centered, and more likely to originate from distributed networks, the means of addressing these threats must also change.

The fifth wave of deterrence development is rising at a point when established international security practices are fumbling to respond effectively to security challenges. Resilience thinking presents a potential breakthrough that can increase the ability of established security institutions to improve their links and address complex threats deliberatively. If institutions can accept the current shift toward resilience as an important and practical one, then the “complex adaptive system” of international security is more likely to meet future system changes or disruption in a more prepared state. The fifth wave of deterrence will be characterized by the network-driven, tailor-made solution.

Deterrence is an uncertain art, not a science, and if the decision-making processes that determine deterrence actions do not match the problems, it is unlikely that practical deterrence solutions commensurate to modern threats can be identified and deployed.

Modern approaches to national and international security are already built on networks, but control tends to remain hierarchical and linear. Dealing with complex threats highlights the necessity to move away from traditional reductionist and hierarchical approaches to problem governance, and to engage existing networks with distributed and deliberative approaches.

To a certain degree, policy failures must be accepted as inevitable in a complex, uncertain, and unpredictable security environment. But policy failures will be more likely if policymaking processes are not suited to this current security environment. If policy processes are deterministic, reductionist, and hierarchical, then they are not suited to governing systems that are characterized by non-linearity, unpredictability of interactions, and uncertain feedbacks. By contrast, if policy processes are designed to match the complex systems and problems they are attempting to govern – i.e., if they are flexible, reactive, and distributed – then they are likely to be more successful.

Notes

1 EU, “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe”, in: A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy, 06.2016, 46.

2 NATO, “Commitment to enhance resilience”, issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw, 08 – 09.07.2016.

3 EU, Shared Vision, 8.

4 White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, 12.2017.

5 HM Government Cabinet Office, National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015: A Secure and Prosperous United Kingdom, 23.11.2015.

6 Ben Buchanan, “Cyber and Calvinball: What’s missing from Trump’s Security Strategy?” in: War on the Rocks, 04.01.2018.

7 David Jordan et al., Understanding Modern Warfare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

8 Adam B. Lowther, “How has deterrence evolved?”, in: Adam B. Lowther (ed.), Deterrence: Rising Powers, Rogue Regimes, and Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 1 – 16.

9 Alex Wilner and Andreas Wenger, “Linking Deterrence to Terrorism: Promises and Pitfalls”, in: Andreas Wenger and Alex Wilner (eds.), Deterring Terrorism: Theory and Practice (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 3 – 17.

10 White House, National Security Strategy, 27.

11 Marie Baezner and Patrice Robin, “Cyber-conflict between the United States of America and Russia”, in: CSS Hotspot Analysis (Zurich: CSS/ ETH, 2017).

12 Jordan et al., Understanding Modern Warfare.

13 Christopher O. Bowers, “Identifying Emerging Hybrid Adversaries”, in: Parameters, 42, no. 1 (2012), 39 – 50.

14 Jordan et al., Understanding Modern Warfare.

15 Carl Folke et al., “Resilience thinking: integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability”, in: Ecology and Society, 15, no. 4 (2012), Article 20.

16 Myriam Dunn Cavelty and Tim Prior, “Resilience in Security Policy: Present and Future”, in: CSS Analysis in Security Policy, no. 142 (2013).

17 White House, National Security Strategy, 27.

18 Christian Fjäder, “The nation-state, national security and resilience in the age of globalisation”, in: Resilience, 2, no. 2 (2014), 114 – 129.

19 John D. Steinbruner, Principles of Global Security (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2000).

20 Franklin D. Kramer et al., NATO’s New Strategy: Stability Generation (Washington D.C.: The Atlantic Council & Center for Transatlantic Relations, 2015), 1.

21 M. Elaine Bunn, “Can Deterrence be Tailored?”, in: Strategic Forum, no. 225, 01.2007.

22 Myriam Dunn Cavelty and Jennifer Giroux, “The Good, the Bad, and the Sometimes Ugly: Complexity as both Threat and Opportunity in National Security”, in: Emilian Kavalski (ed.), World Politics at the Edge of Chaos: Reflections on Complexity and Global Life (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2015), 209 – 228.

23 Lance H. Gunderson and Crawford S. Holling (eds.), Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2002).

24 Jason Hamilton, “On Jargon: 21st Century Problems”, in: The UMAP Journal, 34, no. 4 (2013), 327 – 338.

25 Tim Prior and Florian Roth, “The boundaries of building societal resilience: responsibilization and Swiss Civil defense in the Cold War”, in: Behemoth A Journal on Civilisation, 7, no. 2 (2014), 91 – 111.

26 EU, Shared Vision, 24.

27 Agata Gostyńska-Jakubowska, “Poland’s Prime Minister: New Face, Same Old Tune?”, in: CER Bulletin, no. 118 (2018), 1.

28 David L. Rousseau and Rocio Garcia-Retamero, “Identity, power, and threat perception: A cross-national experimental study”, in: Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51, no. 5 (2007), 744 – 771.

29 White House, National Security Strategy, 13.

30 Tim Prior, “NATO: Pushing Boundaries for Resilience”, in: CSS Analysis in Security Policy, no. 213 (2017).

31 Ben Buchanan, “Cyber and Calvinball: What’s missing from Trump’s Security Strategy?” in: War on the Rocks, 04.01.2018.

32 Andreas Wenger and Alex Wilner, “Deterring Terrorism: Moving Forward”, in: Andreas Wenger and Alex Wilner (eds.), Deterring Terrorism: Theory and Practice (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 301 – 324, here 301.

About the Author

Dr Tim Prior is Head of the Risk and Resilience Research Team at the Center for Security Studies (CSS).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.

No comments:

Post a Comment