Mark Bergen

Last July, 13 U.S. military commanders and technology executives met at the Pentagon's Silicon Valley outpost, two miles from Google headquarters. It was the second meeting of an advisory board set up in 2016 to counsel the military on ways to apply technology to the battlefield. Milo Medin, a Google vice president, turned the conversation to using artificial intelligence in war games. Eric Schmidt, Google’s former boss, proposed using that tactic to map out strategies for standoffs with China over the next 20 years. A few months later, the Defense Department hired Google’s cloud division to work on Project Maven, a sweeping effort to enhance its surveillance drones with technology that helps machines think and see.

The pact could generate millions in revenue for Alphabet Inc.’s internet giant. But inside a company whose employees largely reflect the liberal sensibilities of the San Francisco Bay Area, the contract is about as popular as President Donald Trump. Not since 2010, when Google retreated from China after clashing with state censors, has an issue so roiled the rank and file. Almost 4,000 Google employees, out of an Alphabet total of 85,000, signed a letter asking Google Chief Executive Officer Sundar Pichai to nix the Project Maven contract and halt all work in “the business of war.”

The petition cites Google’s history of avoiding military work and its famous “do no evil” slogan. One of Alphabet's AI research labs has even distanced itself from the project. Employees against the deal see it as an unacceptable link with a U.S. administration many oppose and an unnerving first step toward autonomous killing machines. About a dozen staff are resigning in protest over the company’s continued involvement in Maven, Gizmodo reported on Monday.

The internal backlash, which coincides with a broader outcry over how Silicon Valley uses data and technology, has prompted Pichai to act. He and his lieutenants are drafting ethical principles to guide the deployment of Google's powerful AI tech, according to people familiar with the plans. That will shape its future work. Google is one of several companies vying for a Pentagon cloud contract worth at least $10 billion. A Google spokesman declined to say whether that has changed in light of the internal strife over military work.

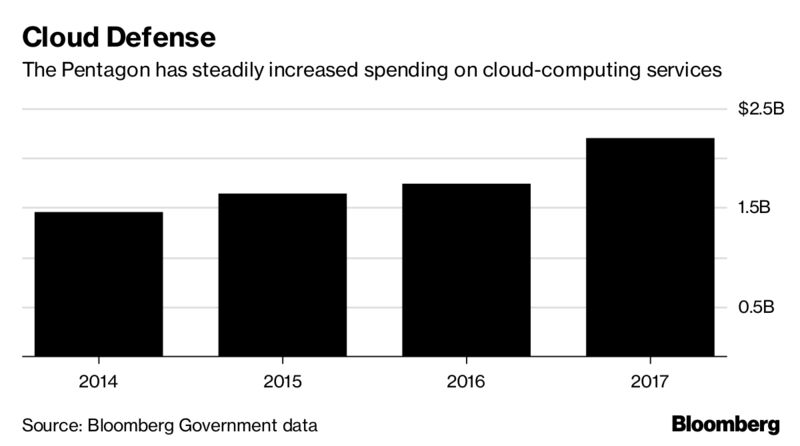

Pichai’s challenge is to find a way of reconciling Google’s dovish roots with its future. Having spent more than a decade developing the industry’s most formidable arsenal of AI research and abilities, Google is keen to wed those advances to its fast-growing cloud-computing business. Rivals are rushing to cut deals with the government, which spends billions of dollars a year on all things cloud. No government entity spends more on such technology than the military. Medin and Alphabet director Schmidt, who both sit on the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Board, have pushed Google to work with the government on counter-terrorism, cybersecurity, telecommunications and more.

To dominate the cloud business and fulfill Pichai’s dream of becoming an “AI-first company,” Google will find it hard to avoid the business of war.

Inside the company there is no greater advocate of working with the government than Google Cloud chief Diane Greene. In a March interview, she defended the Pentagon partnership and said it's wrong to characterize Project Maven as a turning point. “Google’s been working with the government for a long time,” she said.

The Pentagon created Project Maven about a year ago to analyze mounds of surveillance data. Greene said her division won only a “tiny piece” of the contract, without providing specifics. She described Google's role in benign terms: scanning drone footage for landmines, say, and then flagging them to military personnel. “Saving lives kind of things,” Greene said. The software isn’t used to identify targets or to make any attack decisions, Google says.

Many employees deem her rationalizations unpersuasive. Even members of the AI team have voiced objections, saying they fear working with the Pentagon will damage relations with consumers and Google’s ability to recruit. At the company’s I/O developer conference last week, Greene told Bloomberg News the issue had absorbed much of her time over the last three months.

Googlers’ discomfort with using AI in warfare is longstanding. AI chief Jeff Dean revealed at the I/O conference that he signed an open letter back in 2015 opposing the use of AI in autonomous weapons. Providing the military with Gmail, which has AI capabilities, is fine, but it gets more complex in other cases, Dean said. “Obviously there’s a continuum of decisions we want to make as a company,” he said. Last year, several executives—including Demis Hassabis and Mustafa Suleyman, who run Alphabet’s DeepMind AI lab, and famed AI researcher Geoffrey Hinton—signed a letter to the United Nations outlining their concerns.

“Lethal autonomous weapons … [will] permit armed conflict to be fought at a scale greater than ever, and at timescales faster than humans can comprehend,” the letter reads. “We do not have long to act.” London-based DeepMind assured staff it’s not involved in Project Maven, according to a person familiar with the decision. A DeepMind spokeswoman declined to comment.

Richard Moyes, director of Article 36, a non-profit focused on weapons, is cautious about pledges from companies that humans—not machines—will still make lethal decisions. “This could be a stepping stone to giving those machines greater capacity to make determination of what is or what’s not a target,” he said. Moyes, a partner of the DeepMind Ethics & Society group, hasn’t spoken to Google or DeepMind about the Pentagon project.

AI military systems have already made mistakes. Nighat Dad, director of the Digital Rights Foundation, cites the case of two Al Jazeera reporters who filed legal complaints that they were erroneously placed on a drone “kill list” by the U.S. government’s Skynet surveillance system. Dad sent a letter in April to Pichai asking Google to end the Project Maven contract, but says she hasn’t received a reply.

The primary concern for some AI experts is that the existing technology is still unreliable and could be commandeered by hackers to make battlefield decisions. “I wouldn’t trust any software to make mission-critical decisions,” says Gary Marcus, an AI researcher at New York University. Project Maven, Marcus says, falls into an ethical “gray area” since the public doesn’t know how the software will be used. “If Google wants to get in the business of doing classified things for the military, then the public has the right to be concerned about what kind of company Google is becoming,” he says. Google's cloud division is not certified to work on classified projects. A Google spokesman declined to say if the company will purse that certification.

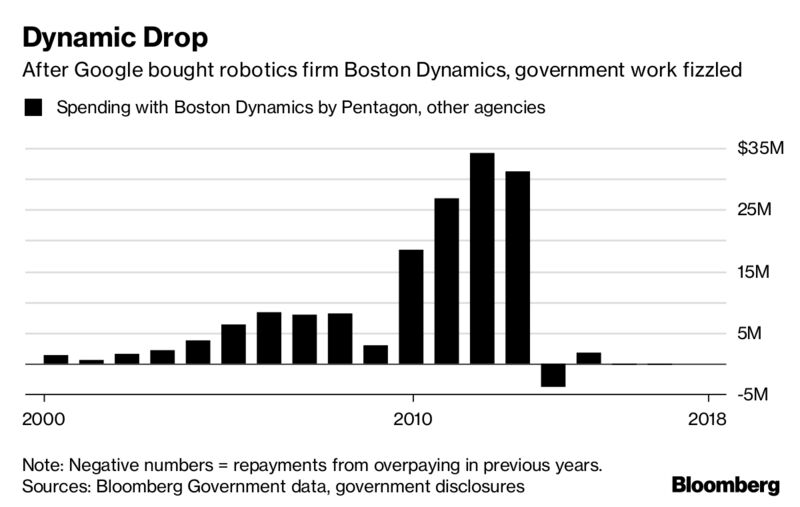

For many years, Google typically exited the government contracts of companies it acquired. In 2011, the year Google bought it, facial recognition startup Pittsburgh Pattern Recognition billed the U.S. $679,910, according to Bloomberg Government data. The next year, Google’s revenue from the U.S. government amounted to less than that. (These figures exclude military spending on Google ads, which are classified numbers and likely equal many millions of dollars a year.) Robot maker Boston Dynamics generated more than $150 million in federal contracts over 13 years before being bought by Google in late 2013. The next year, the contracts ended. (Google agreed to sell Boston Dynamics in 2017).

Since Greene was recruited to run its cloud unit in 2015, Google has become less squeamish about government work. Last year, federal agencies spent more than $6 billion on unclassified cloud contracts, according to Bloomberg Government. About a third of that came from the Defense Department. Right now Amazon.com Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Oracle Corp. are big players. Amazon’s cloud business alone has generated $600 million in classified work with the Central Intelligence Agency since 2014, Bloomberg Government data show.

Greene is determined to compete for such contracts. “We will work with governments because governments need a lot of digital technology,” she said in the March interview. “What’s new, and what we’re having a lot of discussion around, is artificial intelligence.”

After initially wavering on the need for specific AI policies, the Trump Administration is now moving to embrace the technology—a shift driven largely by the looming competitive threat from China and Russia. On April 2, Project Maven received an additional $100 million in government funding. Military officials have cast the program as a key way to reduce time-consuming tasks and make warfare more efficient.

“We can confirm Project Maven involves working with a number of different vendors, and DoD representatives regularly meet with various companies to discuss progress with ongoing projects,” said Defense Department spokeswoman Maj. Audricia Harris. “These internal deliberations are a private matter, therefore it would be inappropriate to provide further details.” ECS Federal, the contractor paying Google for the Project Maven work, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Defense Secretary James Mattis visited Google in August and met with Pichai, Greene and co-founder Sergey Brin. They discussed the company’s cloud and AI advances as well as other opportunities, such as finding new ways to share telecom spectrum owned by the military, another Google project. (Schmidt, who stepped down as Alphabet chairman in December, recently told Defense One that he’s excluded from decision-making about any Google work with the Pentagon. Notes from the July meeting of the Defense Innovation Board were made public online.) Mattis also visited Microsoft and Amazon during the trip.

Some Google executives consider warmer ties with the government long overdue. Five years ago, relations were strained after Google vocally objected to revelations, uncovered by Edward Snowden, that the National Security Agency had tapped the company's networks. A senior executive involved in recent talks says one objective was to avoid the kind of “pissing contest” between Google and the government that happened after Snowden’s revelations.

But the divide inside the company will not be easily overcome. At several Google-wide meetings since March, Greene and other executives were peppered with questions about the merits of Project Maven. One says a recent justification for moving ahead amounted to: If we don’t do this, a less-scrupulous rival will. “The argument they've been using is terrible,” this person says. Another employee says the anti-Project Maven petition, reported earlier by The New York Times, is one of the largest in the history of the company, which is famous for encouraging internal debate. Gizmodo first reported Google staff concern about the company’s involvement. Pichai has addressed the issue with employees, but has yet to answer their demand to cancel the contract.

Google’s CEO didn’t mention the military deal at the I/O conference. Several executives there said privately that they trusted Pichai to make the appropriate decision. The deal didn’t come up at the event’s marquee session on AI either. Fei-Fei Li, who runs AI for Google Cloud, made a passing mention of ethics. “We talk a lot about building benevolent technology,” she said. “Our technology reflects our values.” Greene, sitting next to her on stage, nodded in agreement.

— With assistance by Daniel Flatley and Chris Cornillie

No comments:

Post a Comment