IN FEBRUARY India quietly passed a milestone. The release of its annual budget showed that defence spending, at $62bn, has swept past that of its former colonial master, Britain. Only America, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia lavish more on their soldiers. For nearly a decade India has also been the world’s top importer of arms. In terms of active manpower and the number of ships and planes, its armed forces are already among the world’s top five.

IN FEBRUARY India quietly passed a milestone. The release of its annual budget showed that defence spending, at $62bn, has swept past that of its former colonial master, Britain. Only America, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia lavish more on their soldiers. For nearly a decade India has also been the world’s top importer of arms. In terms of active manpower and the number of ships and planes, its armed forces are already among the world’s top five.

Measured by ambition, India may rank higher still. Its military doctrine envisages fighting simultaneous land wars against Pakistan and China while retaining dominance in the Indian Ocean. Having revealed its nuclear hand in 1998 with a series of tests, India has developed its own ground-hugging cruise missiles and is trying to perfect submarine-launched intercontinental ones, too. Since the Hindu nationalist party of the prime minister, Narendra Modi, took power in 2014 it has also adopted a more muscular posture. Last summer it sparred with China atop the Himalayas in the tensest stand-off in decades. It has also responded to cross-border raids by militant groups from Pakistan not with counterinsurgency tactics and diplomatic ire, but with fierce artillery strikes against Pakistani forces.

Yet a growing chorus of Indian officers, civilian officials and defence analysts appears less than impressed by all this seeming toughness. In mid-March their long-muted criticism burst into the open. Summoned before a parliamentary committee on defence, India’s service chiefs revealed not only dire shortfalls in equipment and investment, but mounting frustration with a pettifogging civilian defence bureaucracy and the government’s penny-pinching ways. Subsequent public debate has gone further, questioning not only poor resource allocation but also the armed forces’ own failure to reform, restructure or revise doctrine.

Judging from the three services’ own testimony, the airing of such grievances is long overdue. MPs were told that some 68% of the army’s equipment, much of which was first supplied by the Soviet Union, such as BMP-2 personnel carriers and Shilka anti-aircraft guns, may be described as “vintage”. Only 8% could be considered state-of-the-art. “To be prepared for...a two-front war, the huge deficiencies and obsolescence of weapons, stores and ammunition existing in the Indian army do not augur well,” said the army’s report.

In its own commentary the committee noted, by way of example, that despite its having repeatedly raised the matter for a decade, the army had still failed to provide soldiers with adequate body armour. The other services are no better: antiquated MiG-21 fighter jets still patrol the skies and the navy’s shipbuilding programme is a decade behind schedule.

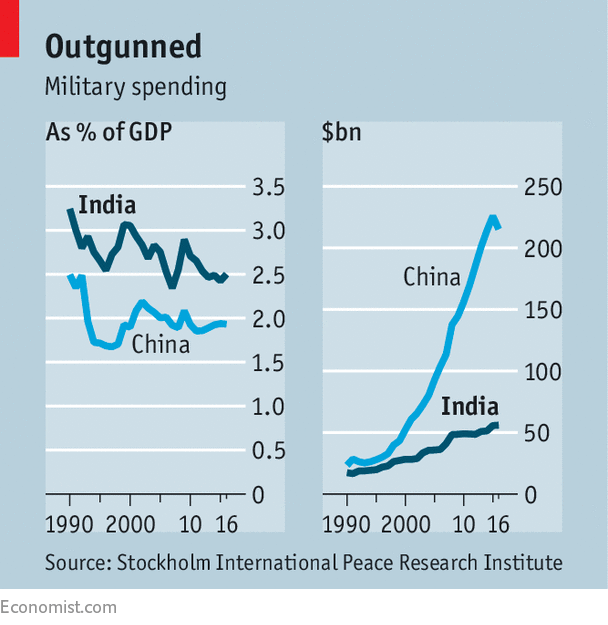

Despite Mr Modi’s chest-thumping, the defence budget has actually shrunk over the past decade as a proportion of GDP and is far below China’s in dollar terms (see chart). More tellingly still, the share of it devoted to capital expenditure has slipped dramatically: for the navy this dropped from 13% in 2014 to below 8% last year; for the air force from nearly 18% a decade ago to below 12% in 2017. A sharp pay rise means that personnel costs will eat up 63% of the army’s budget this year.

If pensions are included, some three-quarters of the overall defence budget will be consumed by salaries and benefits, leaving scant funding for procurement, let alone such luxuries as research and development. Small wonder that foreign investment in the defence industry, touted as a centrepiece of the government’s Make In India campaign to boost domestic manufacturing, amounted to less than $200,000 from 2014 to 2017, out of some $60bn of FDI in 2017 alone.

There are also doubts about how India’s men and women in uniform are being used. Despite increasing pressure on Pakistan, for instance, the number of cross-border violations counted by India has gone up dramatically, from 152 in 2015 to 860 last year, with a consequent rise in casualties on both sides and no movement towards resolving disputes. The number of intrusions from China also rose from 273 in 2016 to 426 last year. India’s refusal last summer to permit Chinese road-building in a patch of disputed Bhutanese territory showed strong nerves, yet what became known as the Doklam incident has not prevented China from massively reinforcing its position in the area.

Brahma Chellaney, a hawkish Indian security expert, noted in an acerbic commentary that Doklam “illustrates that while India may be content with a tactical win, China has the perseverance and guile to win at the strategic level.” The struggle to counter Chinese political and economic encroachment even in zones where Indian influence has seldom been challenged, such as Nepal and the Maldives, also suggests difficulties in projecting influence.

Some of the weakness may be due not to the size of India’s forces, but to their shape. Despite numerous expert reports, internal military recommendations and committee findings calling for integrating both India’s central and regional commands, its army, navy and air force have maintained rigidly independent structures. Whereas China recently streamlined its operational forces into five broad regional commands, India maintains 17 separate single-service local commands.

Meanwhile the defence ministry, which calls the shots on such vital questions as procurement and promotions, is staffed with career bureaucrats and political appointees who lack not only technical knowledge but also, grumble ex-servicemen, much sympathy for people in uniform. Mao Zedong, who foolishly derided America as a “paper tiger”, might have applied similar words to the southern adversary his country faces today.

No comments:

Post a Comment