By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR

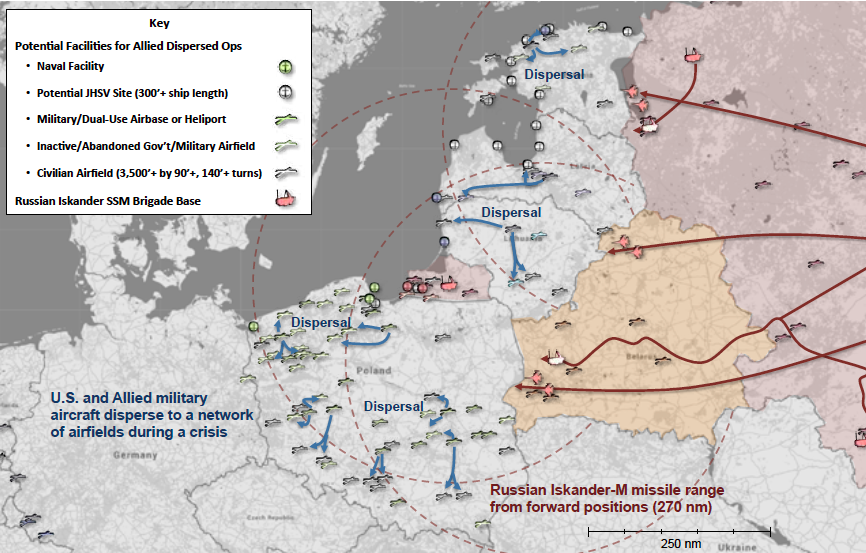

Defense of the Baltic States and Poland against a notional Russian missile barrage. (CSBA graphic)

QUANTICO: Russia or China could “overrun” US allies at the outbreak of war, senior military leaders fear, and our plan to stop them is very much a work in progress. Iraq and Syria have given sneak previews of how the US can combine, say, hackers, satellites, special operators, and airstrikes in a single offensive, but we’re not yet ready to launch such a multi-domain operation against a major power.

“There is a good chance… we’d lose the opening stages of this war,” said one participant in a high-level all-service conference on multi-domain operations held here last month. (I was allowed to attend on the condition I not identify anyone). “Parts of the Pacific, parts of Europe are probably going to be overrun before we can gather ourselves.”

Graphic courtesy Sen. Dan Sullivan

“If deterrence fails, we’re not going to be able to prevent loss of terrain and populations,” the speaker continued. “Just look at the Baltic States,” where every potential target is just a few hours’ drive from the Russian border and the NATO presence — one multinational battalion each in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland — is often dismissed as a “tripwire.” With US allies this exposed, the speaker said, “we’d give ground, and we’d have to consolidate and gather our resources to make a counter push.”

But when we try to counterattack, today’s adversaries won’t allow the US four or five months to mobilize, deploy, and prepare the way Saddam Hussein did twice (in 1990-91 and 2002-3), added another participant: “We’re predictable. They’ve built a system to take advantage of that predictability.”

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis — a former joint commander himself — has pledged to make the US “strategically predictable for our allies” (i.e. dependable) but “operationally unpredictable for any adversary.” Part of being unpredictable is developing ways of fighting, and the concept with the most momentum in the last few years is multi-domain operations. The different US services have long worked with each other in limited ways, most notably when Air Force, Navy, and Marine aircraft support Army and Marine ground forces. But the multi-domain concept wants to jointness to a much higher level: seamless integration of land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace over vast warzones, with each service both assisting and being assisted by the others.

Islamic State (Daesh) fighters

Multi-Domain in the Middle East

The war against the Islamic State provided some small-scale, “episodic” examples of multi-domain operations, one participant recounted. In one case, intelligence had identified a number of the enemy’s primary command posts, but not their backup sites. So rather than just bomb the high value targets and try to figure out where the survivors went, the coalition forces used (unspecified) space and cyber capabilitiesto shut down communications at the primary sites. That forced the enemy leadership to move to their backup locations and turn them on, allowing the allies to target those. The physical strike followed, destroying the backup sites first and the primaries second.

A B-52 heavy bomber arrives in Qatar to join the air war against the Islamic State.

“That’s an example of a multi-domain operation. The first shots were digits, ones and zeroes,” the participant said. “Pretty cool.”

The catch? The whole operation took four or five days, he said, but “it took us three weeks, probably, to organize that operation.”

Why so long? To start, the US didn’t have all the military capabilities and legal authorities required, forcing it to rely heavily on allies. Further, even within the US forces, information didn’t flow freely.

In a single command post, the speaker said, commanders had to make sense of four separate pictures of the battlefield:

data on the current positions of friendly ground units via Blue Force Tracker;

data on friendly air units, which didn’t show up on Blue Force Tracker;

intelligence data, which didn’t feed into either the ground or air systems above;

“a crowd-sourced social media map” that compiled tweets and other social media posts to report where bombings and battles had occurred. This open-source intelligence was at least as accurate as official intelligence sources and considerably faster.

This kludged-together system, taking weeks to bring capabilities together across multiple domains, works okay against the Islamic State, with its ragged ground force, modest cadre of hackers, and complete lack of air, sea, and space assets. But it would be lethally slow against a major power with its own long-range sensors, precision missiles, and big guns.

“We had absolute supremacy in all domains, right, and it still took us weeks to get that together because we didn’t have all the tools or resources or the authorities to be able to do it ourselves,” the speaker said. “(That) won’t work against a near-peer adversary.”

“We’ve got to be able to do in hours what …. took us weeks,” the speaker continued. Instead of such coordination being the exception, laboriously put together for a specific operation, it needs to become the default, part of the day-to-day operations of the armed forces: “Today we episodically synchronize. And in the future we’re going to have to continuously integrate.”

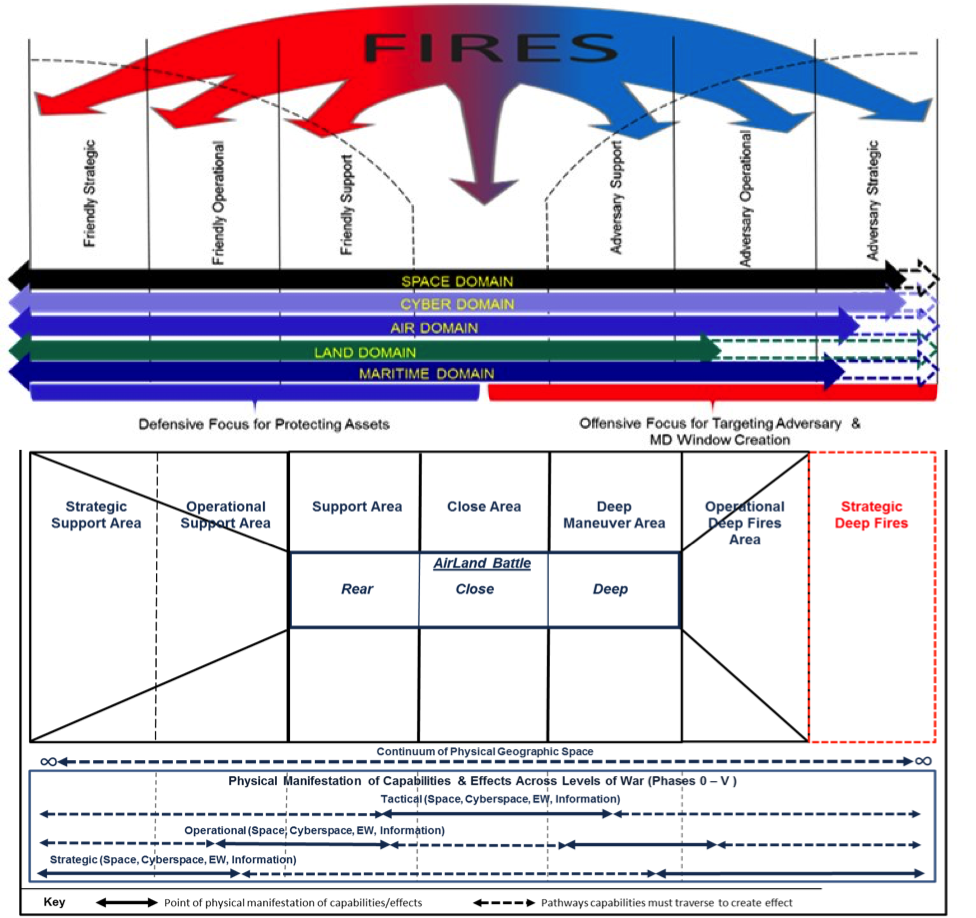

The Army’s battlefield framework for Multi-Domain Battle.

Command, Control, & Chaos

To achieve this integration, “we’re going to have to think very differently about command and control,” said another participant. Instead of relationships between commands staying the same for months or years, for example, who has the lead might suddenly switch to exploit some fleeting opportunity, then switch back again: “One minute you might you might be the supported commander, the next you might be the supporting commander.”

“In the Army…..we love to draw lines on maps,” the speaker continued: This brigade will advance here, this division will hold there. But that won’t work against adversaries with long-range weapons that reach across our tidily bounded boxes. A battalion, for example, might not be able to advance until someone neutralizes an enemy battery firing from hundreds of miles away — but that battery might not reveal its location by firing or redeploying until US ground units threaten it. Who’s in charge of solving that problem? We need a “functional approach,” the speaker said, integrating capabilities like precision firepower or ground maneuver across the entire war zone.

The Air Force already adopts a functional approach that plans for strike, refueling, reconnaissance, and other missions across the entire theater, rather than carving up territory among subordinate commands as in the Army. But the Air Force has its own obstacles moving to Multi-Domain Command and Control (MDC2) operations.

In particular, theater Combined Air Operations Centers (CAOCs) are set up to handle requests for air support coming from the Army’s top echelons, not from lots of widely dispersed, fast-moving brigades as envisioned for future war. “That creates a giant liaison problem,” said one briefer.

The head of Air Combatant Command, Gen. Mike Holmes, has argued the Air Force may need to decentralize its command structure for future wars. One participant today suggested the solution may instead be to create a kind of Uber for airpower: Ground commanders could input their request for a particular type of support — airstrike, electronic warfare, reconnaissance, etc. — and a centralized system automatically matches them with the nearest available asset

The Navy is likewise looking at how to command and control its forces in a larger war. For decades, carrier and amphibious strike groups have operated as independent units, supervised by theater commanders: PACOM in the Pacific, CENTCOM in the Mideast, and so on. Now, the Navy is looking at strengthening an intermediate level of control, the fleet, with potentially multiple strike groups under a single fleet commander and multiple fleets in a theater. Naval operations will “now be synchronized at a much higher level,” one participant explained.

As much as we strengthen command and control, however, we have to expect the enemy to disrupt our plans. When military officers talk about “synchronizing” operations, “(it) implies that we have the ability to precisely synchronize our activities: maneuver, fires, sustainment, command, protection,” warned one speaker. “I think a future near-peer competition is going to preclude that. We’re going to have to accept a lot less precise synchronization.

“It’s going to be rougher,” the speaker continued. “It’s going to look more like an advance in World War II than the advance on Baghdad in (2003) or the attack in Desert Storm.”

That puts a premium on initiative and improvisation. Those are two things, fortunately, that Americans tend to be good at.

No comments:

Post a Comment